Spoilers are discussed. Extensively.

The waves beating violently against the foot of a cliff - the smoldering ruins clouded in a heavy mist - the pristine, untouched room in the west wing, mausoleum for a woman so perfect she seems never to have existed... Rebecca is loaded with Romantic imagery, and as with so much Romanticism a dark secret lies at the heart of all the eerie beauty.

Yet what is significant about this secret is how it shatters the Romantic nightmare and places something coarser, more real, in its place - a reality just as dark but far more tangible than all the doom-laden myths evoked by the aforementioned locales. The mysterious gothic world will come crashing down when exposed to the open air of uncomfortable truths and petty people, to the point where the torching of Manderlay seems almost an afterthought.

Lately I've embarked on a Hitchcock retrospective: over the course of several months, I'm watching all of the director's films, in chronological order. I've done this with Kubrick and Bergman before (it was quite easy with the former, quite difficult with the latter - I was able to view many obscurities, and still missed at least 25% of his output). In both cases, I learned a great deal about the filmmakers, watching their themes, style, and skill develop over the course of their careers.

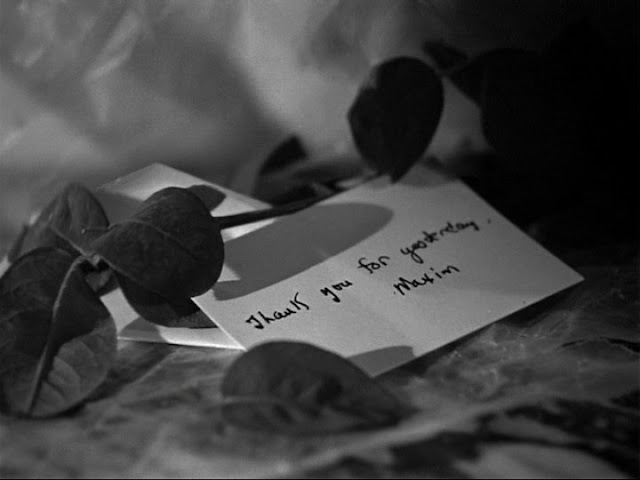

Tonight I reached Rebecca, Hitch's first American film. I saw it years ago, but had forgotten virtually everything about it; I recalled the fire at the end, the psychological torment of Mrs. Danvers, and the gist of the first thirty minutes but otherwise drew a blank on how the story wound itself up. I could recall vaguely that Maxim (Laurence Olivier) was implicated in the death of his wife Rebecca, but didn't remember the context or whether he was innocent or guilty.

As it turns out, he didn't quite kill her, but he did despise her (and unceremoniously dump her body in the sea). We've been led to believe, for over an hour, that Maxim was deeply in love with Rebecca and that he's chosen his new bride as a simple child-wife who will please him but can never reach the depths attained by Rebecca. As it turns out, she was a loathsome man-eater, a merciless manipulator - she was memorable alright, but as a charismatic devil rather than ethereal angel.

What's so brilliant about this twist is that it's unneeded - the film would have worked perfectly well if it was limited to the initial conceit. Most of us can relate to Mrs. de Winter's feelings of inadequacy, of stepping into the room just after someone infinitely more brilliant and charming has left. It is wise to tell the story from her perspective, because it allows us to see her as dull and yet still sympathize with her.

It also allows us to be surprised when that twist arrives, a twist which deepens and strengthens the movie even as it shatters the moody mysteriousness, replacing myth with psychology as the new narrative North Star. And so the story and its meaning change completely. No doubt this shift was in the book, so it would be silly to credit it to Hitchcock, but there are nonetheless the seeds of Psycho's shocking reversal here.

With this change in story comes a change in style. Soon after we find out the truth, the movie leaves behind the halls of Manderlay as it has already abandoned the romantic hills of Monte Carlo and we are rudely relocated to the local village, where Rebecca's "accident" is investigated. I think I may have been disappointed by this turn of events of first viewing, feeling that it burst the eerie mood so effectively established early on.

These scenes do burst the mood, to the film's benefit. Indeed, there's a wonderful gothic air to be savored in the movie's melodrama but by broadening the film's palette, Hitchcock and his collaborators weave an even more enticing web. This sequence is opened by a policeman standing at the door and boasting about a criminal he once captured - an odd flash of humor in a film that up to now has been anything but funny.

It's also the first really Hitchcockian moment in the movie, at least if we're going by what the director had done so far. Indeed, watching this in the wake of all his British work, it's a bit jarring to see how quickly Hitch made the shift to Hollywood, not just physically but mentally - this is an accomplished Hollywood picture, lush and romantic - qualities that Hitchcock had never really displayed before, though they would become hallmarks in many of his future movies.

Surely much of the stylization is due to producer David Selznick and author Daphne du Maurier, and in a way Hitchcock may be breathing a sigh of relief when he gets to the inquiry, as if now he can get down to the brass tacks of chess-like suspense and dark humor. Yet he would adopt this same romanticism for future projects like Spellbound, Notorious, Vertigo, without losing the earthiness or wry humor of the early British films.

Rebecca is a key film in that development but to call it "transitional" would be misleading - the change is so sudden and abrupt that we're a bit taken aback at first. Is this really the same director who fashioned The 39 Steps with its nonchalant hero, The Lady Vanishes with its British common sense, Sabotage with its close study of the petit bourgeoisie?

Though something of a caddish villain, Jack Favell (George Sanders) also serves as a kind of director's surrogate, punctuating the moody insularity of the aristocrats ("my, my, you're quite the little trade union," he drily remarks when they circle wagons against his attempts at blackmail). We recognize the younger Hitchcock more in his character than any other in the film - rather than stare forlornly at a mysterious world, like Mrs. de Winter, or cloak himself in enigmatic removal, like Maxim, Jack climbs right into the house through the open window and leers at the new bride.

Jack is a disenchanted car salesman who took up with Maxim's first wife, suspects Maxim (almost correctly, but not quite) of having had a hand in her demise, and cheerfully uses a letter Rebecca wrote him as bait to open Maxim's wallet. His lack of sentimentality and mercenary streak puncture the world of honor and secretiveness, represented by both Maxim and Mrs. Danvers.

And his presence reminds us that Hitchcock was at heart a middle-class director; the greengrocer's son established himself as such in the very class-conscious England, and he would tweak this preference for American sensibilities by adopting the Everyman as his protagonist in America sometimes a rich Everyman, but seldom an aristocrat.

When recalling Rebecca, everyone remembers the jealous, domineering Mrs. Danvers (beautifully inhabited by Judith Anderson), former personal servant to Rebecca, the moody, mysterious Maxim, the touchingly naive and uncouth Mrs. de Winter, and even Rebecca herself, who is never seen. But in an auteurist sense, it is perhaps Jack who is the key character, a lingering remnant of the British Hitch, drolly holding back on a world he's intrigued by but not yet ready to enter.

And what is that world? If it's the withdrawn, serious world of the aristocracy, the locale of Gothic melodrama and vague mysteries, than Hitchcock did maintain his remove - his scary stories seemed to owe more to the sly playfulness of O. Henry than the gloomy aura of Poe. And yet there is an element to Rebecca which stays, and tightens its hold around Hitchcock's vision like the vines grown around Manderlay once abandoned.

Call it "romanticism" or "darkness" - the ability to find that aristocratic anxiety in the common man and woman, a gift the 20th century offered and which Hitchcock notably accepted. Watching Rebecca, I was particularly reminded of Vertigo, another film involving the haunting memory of a dead woman, a gothic world of mystery and romance beyond the grave, and a scenario that turns out to be not at all what it initially seemed.

In that sense, Manderlay may have been burned to the ground, but it was not forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment