This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Paris Belongs to Us, France, 1960, dir. Jacques Rivette

Starring Betty Schneider, Giani Esposito, Françoise Prévost, Daniel Crohem, François Maistre, Jean-Claude Brialy, Jean-Luc Godard

Story: Anne Goupil is slowly drawn into a mysterious and complicated plot involving her brother's bohemian circle of friends, one of whom is directing her in a play. She slowly discovers that Juan, a young musician and supposed suicide, may have been murdered, either by the femme fatale Terry or a worldwide conspiracy of fascists...or both, or neither. (review contains spoilers)

"I want to tell you that the world isn't what it seems."

- Philip Kaufman

"It's shreds and patches, yet it hangs together over all. Pericles may traverse kingdoms, the heroes are dispersed, yet they can't escape, they're all reunited in Act V. ... It shows a chaotic but not absurd world, rather like our own, flying off in all directions, but with a purpose. Only we don't know what."

- Gérard Lenz

"I speak in riddles but some things can only be told in riddles."

- Philip Kaufman

• • •

The movie is also, among other things, a tale of innocence lost, a meditation on its own creation, and a mournful epitaph for the solidarity and purpose of an earlier (or perhaps imagined) era. If its overall shape is potentially less satisfying than the more confident debuts of Rivette's peers, the movie remains one of the most original and ambitious New Wave films: not just a declaration of style or sensibility, but the halting articulation of a worldview, one more engaged - for all its obscurity and self-enclosement - with the intellectual zeitgeist than the more personalized visions of Truffaut or the movie-movie musings of Godard (excepting Le Petit Soldat). It was also a much harder film to make than The 400 Blows or Breathless: though initiated before other New Wave films, back in 1957 (the film opens with a title placing it in the summer of that year), it was not completed or revealed until 1960 (or 1961, depending upon your source). Equipment was borrowed, actors were begged for their time, the movie was assembled in bits and pieces - a condition humorously reflected in the play-within-a-movie, as theater director Gerard struggles with a rotating cast, a haphazard rehearsal schedule, and eventually the humiliation of big-time backing as a wealthy producer bankrolls his work while overriding his creative decisions.

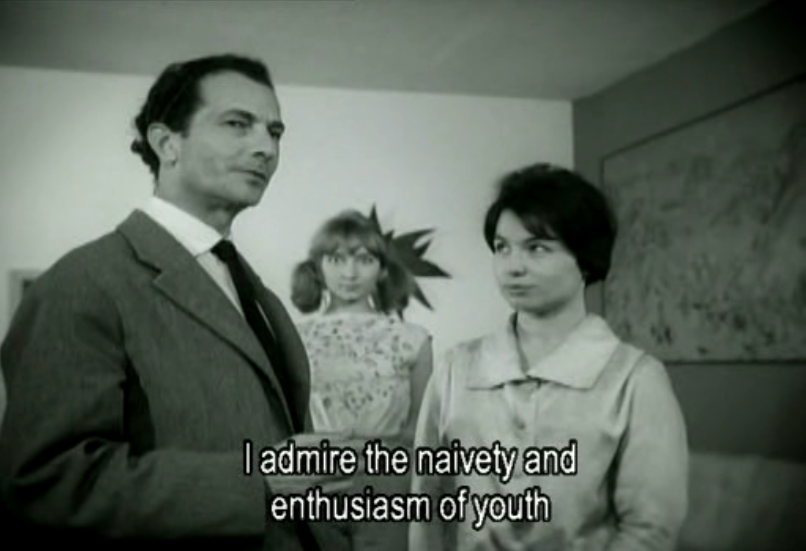

Unlike the farcical, ultimately tragic, production at its center (Rivette's later L'Amour fou and Out 1 would also structure themselves around endless rehearsals overseen by quixotic directors), Paris Belongs to Us remains Rivette's through and through. That he is not yet fully certain of his purpose or fully in control of his means adds a kind of touching resonance to the movie: an arrogant economist's statement that he "admire[s] the naivety and enthusiasm of youth" (while his silent ingenue companion spikes the camera with a vengeance) has a double edge. On the one hand, Rivette, like the economist, stands on the outside looking at Anne's girl-detective with warmth and pity, while regarding her older but still relatively young artist pals with a mixture of fascination and trepidation. On the other hand, the film itself - the fact that it was made, and the struggle of its making and unfolding, reflects Rivette's own youthfulness, his willingness to shoot for something perhaps unattainable. He's a bit like Anne too: exploring a world he doesn't quite understand yet, moving forward into the mystery with determination and hesitation in equal measure. This mysterious intoxication is most pungently evoked in a sequence soaked in the exotic atmosphere of Indian music, in which the strangeness of the soundtrack and the strangeness of the dialogue slither around one another, squeezing Anne in a serpentine embrace.

Much like a later winsome, amateur detective (David Lynch's heroine in Mulholland Dr., also naive, also in over her head), this Francophone Nancy Drew will discover not a tidy resolution with the last puzzle piece, but rather death, the exposure of paranoia as self-justification, and worst of all, an end to the innocence which both fostered her initial curiosity and is incompatible with the outcome of said curiosity. She's trekked into the Wild Wood and can't go home again - if there is a deadly secret shared amongst the sad-faced bohemians of brother Pierre's demimonde, it's this irony: youthful romanticism leads one to explore the dark corners, and what's found in these dark corners is the death of that very romanticism. This wisdom is expressed imperfectly within the film which (mistakenly?) decides to make its conspiracy theory concrete rather than vague. Eventually we learn that the web which threatens American playwright Philip Kaufman (an exiled victim of McCarthy) is not just a nebulous, vaguely metaphysical web of intrigue and malevolence, but specifically a collection of fascists hoping to reclaim their mission of a dozen years previously, this time with more subtlety and total control than before.

This politico-historical "answer" to the paranoid questions of Paris' coterie is both too generalized and too concrete to work: on the one hand, its scope is so broad as to be comically vague (surely part of Rivette's point, though it tends to prematurely torpedo the essential draw of his conspirators), on the other hand locating the metaphysical dread in a specific historical phenomenon diffuses the magic, nightmarish quality of the paranoia just a bit. In his epic Out 1 Rivette would strike the perfect balance between contextual suggestion (his intrigue in that film refers obscurely and obliquely to the uprising of May '68) and metaphysical vagueness (history alone does not explain the overwhelming mood of dread, anxiety, and longing which infuses that movie's mystery). Yet if Paris Belongs to Us goes too far in "explaining" its conspiracy, this explanation nonetheless opens up a just-as-fascinating can of worms. With is Beatlike exiles, its "young" characters still old enough to have fought at Midway, its disconnect between the freshness of Anne and the world-weariness of her (slight) elders, Paris Belongs to Us serves as a fascinating missing link between the fifties and the sixties. It reminds us that the New Left and counterculture of the later era, the era which the New Wave would help usher in, did not arise sui generis but had its roots in the longings, frustrations, and disappointments of earlier generations.

And the film reaches further back than the fifties, into the thirties when the anti-fascist Popular Front locked arms with the artistic avant-garde, and youthful rebellion seemed a force to be reckoned with. Indeed, the Spanish Civil War in Paris Belongs to Us serves roughly the same function as May '68 does in Out 1: a historical marker which allows the protagonists to see where they've been and to remind themselves of the struggle that seems to have dissipated but in fact continues under the surface. Of course, in Out 1 this marker was only two years in the past, whereas in Paris the halcyon days of active resistance are long-gone - this sense of distance marks Paris with a more melancholy mood than Out 1 (in whose veins the hot blood of revolution and riot still race relatively unslowed). Anne's initiation into the world of the left - which is what Juan, Philip, and Terry ultimately represent - is an initiation into despair, disappointment, and intramural violence (the focus is on killing traitors rather than oppressors). The secret is not only that an oppression exists, but that resistance is futile, impotent and self-defeating. This pessimistic vision very much belongs to the fifties rather than the sixties - a time when conformity ruled, McCarthy and HUAC firehosed the left, and meanwhile the Soviet experiment was finally and fully revealed as a charade, giving the last desperate utopians nothing left to cling to.

The crowd of critics and nascent filmmakers at Cahiers du Cinema (where Rivette, and all the other New Wave filmmakers, still worked in '57) was an interesting bunch: aesthetic rebels, prone to give the finger to authority figures, they were politically much more ambivalent (part of that ambivalence was due to the fact that, in France at least, the Old Left was part of the Establishment). Francois Truffaut's famous polemic, "A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema," is remembered for coining the phrase "auteur" and sounding an aesthetic declaration of arms for the director, open to the world with his camera, rather than the writer, enclosed on the typed page. But the polemic is far more complex and surprising than that. For one thing, Truffaut takes the screenwriters to task for not being faithful to the books they were adapting; and specifically, he scolds them for mixing their own political views (left-wing and anti-clerical) in with the material. Perhaps having imbibed some of his mentor Andre Bazin's Catholicism, Truffaut extends his critique not just to the methods but the views of the writers, growling about the "uniformity and equal filthiness of today's scenarios," and bemoaning how "under the cover of literature - and, of course, of quality - they give the public its habitual dose of smut, non-conformity and facile audacity." Truffaut is too sophisticated make his attack simply puritanical, and so his essay is at once more reactionary and more rebellious than the work of the elders he attacks. "The dominant trait of psychological realism," he writes bitingly, "is its anti-bourgeois will. But what are Aurenche and Bost, Sigurd, Jeanson, Autant-Lara, Allegret, if not bourgeois...?"

The following dozen years would sound this same note, and not just on Truffaut's part. Claude Chabrol, the first of the Cahiers group to make a feature, saw Le Beau Serge attacked as right-wing and anti-poor by Luis Bunuel and Roland Barthes. As Amber McNett notes in "The Politics of the French New Wave," "Chabrol responded to Barthes...'The truth is, truth is all that matters.' That, simply, was the crux of the argument between Left and Right. The Left wanted a utilitarian art of grand moral transformation, the Right only wanted to play with, examine, and expose reality as an exercise in truth." With this aesthetic definition of left and right in mind, it's no wonder that even an enfant terrible like Jean-Luc Godard scoffed at the left and was often associated with figures on the hard-right. And yet when the leftist critics lambasted the Cahiers writers as right-wing, they were only half-correct. For one thing, the group was more a(and anti-)political than they were explicitly anti-leftist; for another, when they did make political statements they were more often liberal than conservative. Truffaut signed a letter condemning the Algerian War and Godard crafted Le Petit Soldat, a profoundly ambivalent (if hardly left-wing) take on that same conflict. Later, as Vietnam escalated and the postwar generation emerged to create the New Left, merging aesthetic experimentation and youthful rebellion with radical politics (redeeming the former for old Marxists, and the latter for Young Turks), most of the New Wave filmmakers would move to the left: Jean-Luc Godard, most notably, throwing his lot in with the fanatical Maoists around the time of La Chinoise.

And yet La Chinoise is a subtly ambiguous film - at once reverential and mocking of its protagonists' half-playful, half-deadly serious devotion to the Little Red Book (and their own deeply romantic anti-romanticism). This brings us back to Jacques Rivette - the only one of the central five Cahiers writers to be consistently described as "left-wing." Yet if his films are any evidence, Rivette is anything but a full-throated ideologue. In Paris Belongs to Us, he regards the martyrdom of his heroes with a mixture of sympathy and abhorrence (Philip more often seems boorishly self-pitying than nobly suffering), and sees the zealous confidence of their resistance as both exciting and appalling (Anne's flirtation with the us vs. them mentality of her elders leads to inadvertent fratricide). Notably, he does not place their resistance in the context of what they are resisting (other than the character of the theatrical impresario) - and suggests that their attachment to worldwide struggles and hidden webs of intrigue may be romantic and sentimental. (Not for nothing does he screen the "Babel" sequence from Metropolis near the end of the movie; even if the world seemed to make sense twenty years ago, Rivette seems to be saying, it has disintegrated into an impenetrable web of cross-talk and cross-purposes.)

In Rivette's universe, political commitment becomes a matter of existentialism rather than pragmatism. These revolutionaries are not fighting for the proletariat, but for themselves. This is perhaps the strongest way in which Paris Belongs to Us foreshadows the sixties. If the narrowness of the film's focus makes an odd fit with the breadth of its concern, this combination nonetheless remains compelling, exciting, and intriguing. The film's ethos is summed up by the opening Peguy quotation: "Paris belongs to no one" - and yet through the adventurism of its style and the ambition of its vision, Paris Belongs to Us earns the ironic affirmation of its title.

This entry concludes The Sunday Matinee series - thanks for following.

Read the comments on Wonders in the Dark, where this review was originally published.

No comments:

Post a Comment