Showing posts with label sunday matinee. Show all posts

Showing posts with label sunday matinee. Show all posts

The Sunday Matinee: Paris Belongs to Us

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

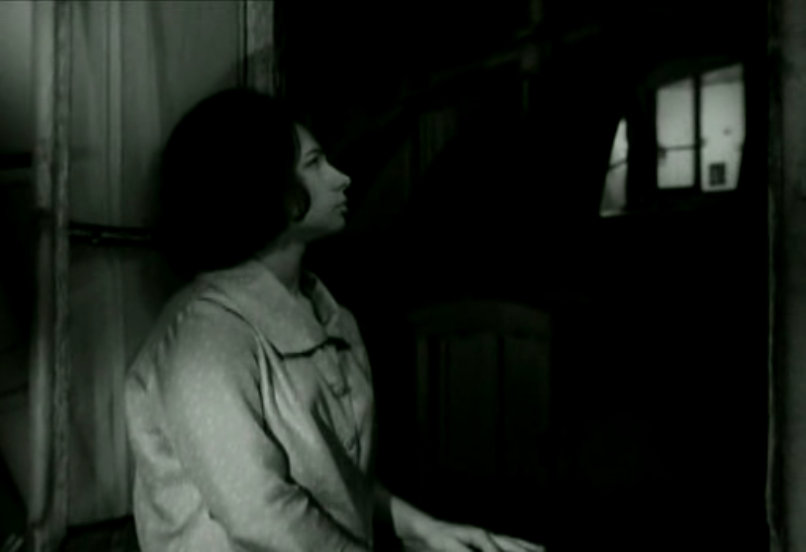

Paris Belongs to Us, France, 1960, dir. Jacques Rivette

Starring Betty Schneider, Giani Esposito, Françoise Prévost, Daniel Crohem, François Maistre, Jean-Claude Brialy, Jean-Luc Godard

Story: Anne Goupil is slowly drawn into a mysterious and complicated plot involving her brother's bohemian circle of friends, one of whom is directing her in a play. She slowly discovers that Juan, a young musician and supposed suicide, may have been murdered, either by the femme fatale Terry or a worldwide conspiracy of fascists...or both, or neither. (review contains spoilers)

"I want to tell you that the world isn't what it seems."

- Philip Kaufman

"It's shreds and patches, yet it hangs together over all. Pericles may traverse kingdoms, the heroes are dispersed, yet they can't escape, they're all reunited in Act V. ... It shows a chaotic but not absurd world, rather like our own, flying off in all directions, but with a purpose. Only we don't know what."

- Gérard Lenz

"I speak in riddles but some things can only be told in riddles."

- Philip Kaufman

• • •

The Sunday Matinee: Cleo From 5 to 7

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Cleo From 5 to 7, France, 1962, dir. Agnes Varda, starring Corinne Marchand

The visual touchstone of French New Wave cinema is a character wandering down the real-life streets of Paris, trailed by a handheld camera or preceded by a makeshift dolly: think Jean Seberg shouting "New York Herald-Tribune!", Jean-Pierre Leaud playing truant, Bernadette Lafont pretending to ignore flirtatious overtures from a passing car, or Betty Schneider ducking into a cafe to discuss a mysterious disappearance with Jean-Luc Godard. This visual tradition traveled through time when Jules and Jim brought the New Wave spirit to prewar bohemia, parading down the period avenues and alleys. Truffaut's big hit seemed to capture the restless motion of a whole generation at the dawn of a new, exciting era in art and life alike (although in its ending it contained foreshadowings of the frustrations, disappointments, and uncertainties to come).

Then "the walk" crossed the Channel in 1963 with Julie Christie's daffy, free-spirited stroll through a Yorkshire town in Billy Liar, and it crossed the Atlantic when Liar's director John Schlesinger set Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman loose in a downbeat, grimy New York - by then, the sixties had taken a darker turn. (In 1974, Louis Malle would turn the French "city-walking film" on its head: rather than follow one character with a moving camera, he fixed the camera in place, allowing it to glimpse into the lives of all the passerby who crossed its path.) But no film more perfectly captures or fully explores the potential of this method than Cleo From 5 to 7, Agnes Varda's second feature and her first fictional film since 1955's Le Pointe-Courte, a documentary-narrative hybrid, which preceded the New Wave.

The Sunday Matinee: Les Bonnes Femmes

Les Bonnes Femmes, France, 1960, dir. Claude Chabrol, starring Bernadette Lafont, Clotilde Joano, Stéphane Audran, Lucile Saint-Simon

When, all at once, a new group of young filmmakers arrives on a national scene, there may share some common wellspring. In the U.S., it was often an apprenticeship under Roger Corman (Coppola, Scorsese, Bogdanovich, and Hopper all made early B movies with the prolific independent producer). In Czechoslovakia and other Eastern European countries, the new generation came through the state-run film schools; in the UK, the "kitchen sink" realists were usually documentarians before they made narrative features. In France, the situation was more incestuous than most. If you were to pick the ten or so major French filmmakers to emerge in the French New Wave, at least half of them came from Cahiers du Cinema, the fiery, controversial, and influential start-up film publication. In the late fifties, right around the time Cahiers editor and New Wave mentor Andre Bazin died, Claude Chabrol, Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Jacques Rivette, and Eric Rohmer all began work on their first features. It was Chabrol who hit screens first, with Le Beau Serge (about a young urbanite visiting the provinces) but Truffaut and Godard were the ones who brought attention to the movement, with The 400 Blows and Breathless. In some ways, Chabrol was the odd man out of the five.

The Sunday Matinee: Miraculous Virgin

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

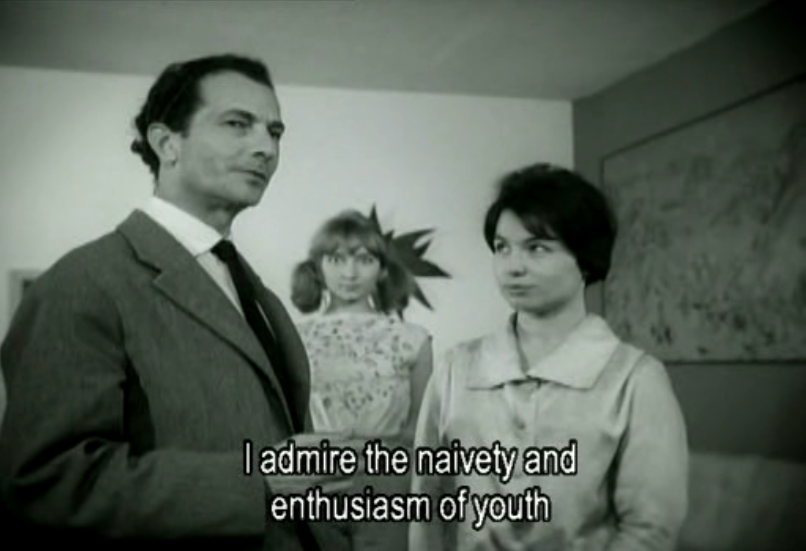

Miraculous Virgin, Czechoslovakia, 1967, dir. Stefan Uher, starring Jolanta Umecka, Ladislav Mrkvicka, Otakar Janda

Story: As bombs fall from the sky, a beautiful young woman wanders into the lives of several young artists and a melancholy middle-aged sculptor. They treat her as their muse. Yet before long, she is overwhelmed by their aggressive attention, and they are frustrated by her aloof resistance to their overtures.

An interesting element of the various European New Waves is their relationship with the recent past - namely World War II. I've often felt that the sixties were imbued with the displaced spirit of the forties, and that the cultural explosion and political upheaval of the era may have been impossible without the misery, death, and displacement of two decades before. This is not to say that the war played a huge role in cultural artifacts of the time; in some ways, the influence was indirect, in others displaced. In certain countries, for example the United States or Britain, the war was considered property of the older squares, and youthful revelers, rebels, or activists either satirized or ignored the earlier era's sensibility. Elsewhere, the war haunted the cinema without necessarily being foregrounded: in France, it popped up in the films of Alain Resnais (about ten years older than most of the other New Wavers); in Italy and Japan, a sense of collective guilt fed into the bitterness with which young filmmakers scorned the societies of the past. Whatever the country, New Wavers tended to be born around the same time period, from the late twenties to the mid-thirties (some a bit younger in Italy, some a bit older in Britain), making them teenagers at the time of the war. This meant that most did not serve as soldiers, and would only have experienced the turmoil of the time to the extent that war came to them.

Czechoslovakia, in some ways, was spared the most brutal aspects of the war. Unlike Britain, Poland, Germany, or Japan it was not subjected to substantial aerial bombardment, one reason that Prague still remains the glistening city of the past, architectural jewels from earlier centuries still dominating its skyline. Yet this was precisely because the Germans didn't need to bomb the Czechs - the country had already been handed over to Hitler by allies eager to appease, and Czechoslovakia was given the dubious honor of enduring Nazi occupation from months before World War II even began. Following the war, unlike the French, Italian, or British, the nation was not able to stumble towards a new sense of independence or democracy; it was occupied by the Soviets, democratic officials were killed, and a Stalinist dictatorship was installed within several years of the "victory." In some ways, for Czechoslovakia, the war never ended. No wonder then, that World War II features so prominently in the Czechoslovakian New Wave (and here it makes sense to use the country's full name, as Miraculous Virgin was directed by a Slovakian, not a Czech). Some of its most famous films - including the Oscar-winning Closely Watched Trains and The Shop on Main Street - take place during the war. The best of these (and the least well-known) is the phenomenal Miraculous Virgin - while the setting is ambiguous, the film is tormented by a sense of occupation, persecution, death, and collaboration. Its themes are universal, but the historical experience of this beleaguered nation is the context out of which Miraculous Virgin was born.

The Sunday Matinee: Daisies

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Daisies, Czechoslovakia, 1966, dir. Vera Chytilová, starring Ivana Karbanová, Jitka Cerhová

...Though I'm not sure I'd call it a "story."

Daisies opens and closes with images of war. The opening credits intercut the grinding mechanisms of wheels and cogs with shaky aerial footage of bombardments. The film ends suddenly with one last image of a (Vietnamese?) countryside being strafed, along with the slow-boiling, deadpan tribute of the filmmaker to her would-be censors: "This film is dedicated to those whose sole source of indignation is a messed-up trifle." The visual carnage is appropriate, for seemingly contradictory reasons. On the one hand, it gives a real-world analogue to the devilish destruction unfolding throughout the movie, and perhaps suggests that the aggressive but not physically violent behavior of its heroines could eventually lead in this deadlier direction - or at least that it's part of the same continuum, selfish decadence leading to bloody chaos. On the other hand, there's an apocalyptic tenor to the war footage, which contrasts sharply with the free-spirited bonhomie of our leading ladies - the suggestion is that this ugly world is what they're rebelling against. Seen this way they are the embodiment of the contemporary countercultural ethos, thumbing noses at conservative social forces be they masked as American imperialists or Stalinist bureaucrats.

And on yet another hand (anatomically incorrect perhaps, but in the spirit of a film which shatters all rules of propriety and perspective) the documentary authenticity of those fleeting shots casts a gloom over the completely and flagrantly fabricated playfulness of the protagonists, giving it an unreal and desperate air. So perhaps there is no direct relationship (either positive or negative) between the world's war and the girls' anarchy, but rather a tension unresolvable in their favor - this grim reality lends a certain fragility to their antics, justifying their aggression and threatening their larks with an air of impending doom. All of these interpretations are, of course, valid but ultimately interpretations are - if not beside the point - at least after the fact. This is a film to be experienced more than "understood" - a wild ride through colors, cuts, iconic images, jagged suggestions, lavish set pieces, roundabout dialogue, and alarmingly incessant and aggressive noises (the sound collage "score," mixing speedily-played classical compositions, random sound effects, and avant-garde atonal exercises, is as much a part of the experience as anything onscreen). It's a tale told by an imp, full of sound and fury, signifying everything.

The Sunday Matinee: Loves of a Blonde

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Loves of a Blonde, Czechoslovakia,1965, dir. Milos Forman, starring Hana Brejchová, Vladimír Pucholt

Story: A young woman sleeps with a charming young pianist; when she pursues him to Prague, she discovers that he did not take their romance as seriously as she did.

The title, like so much else in Milos Forman’s second feature, is gently ironic. With its plural “Loves,” it suggests a worldly figure, a free-spirited sixties girl who rounds up loves, and lovers, with a sense of carefree fun. At the same time, “a Blonde” implies a symbolic woman more than an actual one, probably a silly girl who falls in love and breaks hearts without knowing her own power and/or foolishness. Well, the blonde in Loves of a Blonde, Andula (Hana Brejchová), is rather foolish. And in the course of the movie, she does upset and befuddle at least one boyfriend, by recoiling from him without telling him why. Yet at film’s end, she has had only one real lover, and it was her heart that was broken, not his. Most importantly, Andula is not Julie Christie sent to Prague – not a swinger, but a dreamer, a naïve young woman who is not responding to a new freedom but reacting to a lack thereof. Just as the Prague Spring would flourish for a brief period, before Soviet tanks re-imposed a totalitarian regime for another two decades, so Andula’s season of hope is short. When we last see her, she is back in the factory toiling away, sad and quite alone. Though Loves of a Blonde is a comedy, and a very funny one, at its core is a tragic (albeit still romantic) sense of life.

The Sunday Matinee: This Sporting Life and Billy Liar

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

The Sunday Matinee is a series exploring various national cinemas of the 60s – Italian, British, Czech, and French. Usually, the approach is film by film but this week is an exception. This admittedly rather long essay takes a wide view, not just of the two films in question, but of the British New Wave as a whole, and how these particular movies relate to it. Both reviews contain spoilers.

This Sporting Life, UK, 1963, dir. Lindsay Anderson, starring Richard Harris, Rachel Roberts

Story: Frank Machin, a working-class bloke made local hero in a rugby league, tries to establish a relationship with his widowed landlady, but neither of them can escape their past – she because of her suicidal first husband, he because the patriarchs owning his team never let him forget to whom he owes his success.

• • •

Billy Liar, UK, 1963, dir. John Schlesinger, starring Tom Courtenay, Julie Christie

Story: Billy Fisher uses imagination to get him through a life filled with boring dead-end jobs, multiple fiancées, and crushed hopes, but his active fantasy life is challenged by Liz, a free spirit who pushes him to live out his dreams in the real world, rather than in his mind.

The Sunday Matinee: Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, 1960, dir. Karel Reisz, starring Albert Finney, Rachel Roberts, Shirley Anne Field

Story: Arthur Seaton spends the week working in a factory, and the weekend winning drinking contests, sleeping with a co-worker's wife, and generally pissing off everyone in sight.

When the British New Wave hit cinemas in the early 60s, with its unprettified portraits of working-class life, it was seen as part of an overall cultural trend, already predominant in literary and theatrical works (from which many of these films, this one included, were adapted): the rise of the "Angry Young Man." In Look Back in Anger, he's a snarling young Richard Burton, lashing out at his lover yet displaying a wounded pride when she lashes back. Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner spots him at a borstal, where Tom Courteney runs from authorities until the authorities actually want him to run, at which point he stops. This Sporting Life tackles Richard Harris on the rugby field, A Kind of Loving traps an upwardly mobile Alan Bates in an unwanted marriage, and A Room at the Top locates Laurence Harvey's insecurity and exploits it through a frustrating relationship with an older, wealthier woman. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning may be the purest take at this iconic figure, unfettered as it is by the apparatus of an athletic narrative or the demands of an equal female protagonist (Roberts and Field, both excellent, are definitely supporting characters here). Yet Albert Finney, as Arthur Seaton, does not initially seem as bitter, desperate, or frustrated as any of those other furious youths - as his opening narration informs us, "I'm out for a good time - the rest is propaganda!" And indeed, in the picture above we see him grinning after falling down a flight of stairs, drunk as a skunk but flush with victory after out-drinking a sailor. Sprawled out on the floor, he couldn't seem happier but make no mistake: he's angry as fuck.

The Sunday Matinee: The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, UK, 1962, dir. Tony Richardson, starring Tom Courtenay, Michael Redgrave

Story: Colin has been sent up for robbing a bakery, but to his surprise he finds himself being handed advantages and privileges at the reform school. As it turns out, he’s a talented runner and the school director hopes he will help defeat a prestigious public school in an upcoming race.

First things first, the timing of this entry is no accident. This morning the New York Marathon kicks off – so good luck to all the runners, particularly my friends Patrick and Morgan. Secondly, tributes aside, it should be noted that this is in many respects an anti-sports film, both in the sense that it thumbs its nose at “sports film” conventions, and because it views competitive athleticism itself with severe antipathy. But more on that by the by. When we are introduced to Colin, he’s pulling double duty, running and narrating just like Fabrizio at the start of last week’s entry, Before the Revolution. There the similarities more or less end. Whereas Fabrizio was politicized in theory but distanced from any sense of class struggle, Colin – without necessarily articulating it in explicitly political terms (save for a few somewhat clumsy “consciousness-raising” lines of dialogue) – views his entire life as one long struggle against authorities and class constrictions. “Running’s always been a big thing in our family,” he tells us in the opening narration (during which, unlike Fabrizio, he runs away from the camera rather than towards it). “Especially running away from the police. It’s hard to understand. All I know is that you’ve got to run. Run without knowing why, through fields and woods, and the winning post’s no end even though barmy crowds might be cheering themselves daft. That’s what the loneliness of the long distance runner feels like.”

The Sunday Matinee: Before the Revolution

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Before the Revolution, Italy, 1964, dir. Bernardo Bertolucci, starring Adriana Asti, Francesco Barilli

Story: In Parma, a young Communist feels torn between his romantic hunger for life, the security of his bourgeois background, and his ideological duty to the cause. Meanwhile, he carries on an affair with his emotionally unstable aunt.

The opening scene of Before the Revolution, or Prima della rivoluzione as it’s more poetically known in Italy, stands among the most elating passages in cinema. You can’t quite pinpoint how this works; trying to relate the alchemy of these moments in typed prose, my fingers tie themselves in knots. Bertolucci, only twenty-two when he shot the movie, would go on to direct more lush, illustrious sequences especially once he began to use color. But somehow here we feel we are getting closest to the pulsating consciousness powering his vision - a sensitivity and sensibility swooning with the pregnant possibilities and numinous actualities of the moment. What exactly do we see? Close-ups of Fabrizio (Frencesco Barilli), our hero, which loom like wall-sized portraits, even on a small screen; soaring overhead shots of Parma as if Bertolucci began to run through his hometown and in his enthusiasm sprouted wings and began to fly. What do we hear? Fabirizo’s neurotic narration, a mixture of lush language and furious, uneasy denunciation, underpinned by Ennio Morricone’s lush, heart-bursting score – fully invested in its sense of operatic intensity, and as unashamed of it as Fabrizio is wary. This film then is a sensuous experience, maybe even first and foremost, but it is also a film of ideas, and a dialectic exists between Fabrizio’s notions and his feelings (as well as amongst the various feelings themselves).

The Sunday Matinee: Il Posto

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

This series is going to continue with European classics from the 60s, with three in turn from a given country - Italy, Britain, Czechoslovakia, perhaps France. After Fists in the Pocket last week, the Italian theme continues with...

Il Posto, Italy, 1961, dir. Ermanno Olmi, starring Sandro Panseri, Loredana Detto

I once read a cartoon featuring an old man lying in bed, covers pulled up to his nostrils. Next to him, an obnoxiously cheerful wife hovered, chirping, “Wake up, honey! Today’s the first day of the rest of your life!” The next panel switched to a courtroom, with the sleeping man standing in the docket and a judge slamming down his gavel. A speech balloon conveyed the verdict - “Justifiable homicide, case dismissed.” A curious anecdote with which to introduce Il Posto, because the cartoon’s arch cynicism could hardly be more out of tune with Ermanno Olmi’s warm, open humanism. Yet it serves to set the film in stark relief, because Il Posto also opens with a character in bed, his eyes wide open, a mother rather than a wife calling out to him. There are times in one’s life where clichés shake off the accoutrements of familiarity and take on a fresh, glowing meaning - “oh, that’s what they meant,” we think to ourselves. If someone told Domenico Cantoni, “Today is the first day of the rest of your life,” he would know exactly what they meant, and it would not be cause for a bitter, murderous outburst but rather excitement, anticipation, worry, and a bit of fear.

The Sunday Matinee: Fists in the Pocket

This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Fists in the Pocket, Italy, 1965, dir. Marco Bellochio, starring Lou Castel, Paola Pitagora

Story: A restless, intermittently fitful young man seeks an escape - violent, if necessary - from his provincial villa and oppressive family.

Fists in the Pocket begins with a threatening note, but this j'accuse is just a bad joke. (Disturbing letters will recur throughout the movie, but the written word is an afterthought here; these characters, barbarians after a fashion, write their lives with their bodies and motions, not with mind or pen.) Composed in childlike fashion, words cut out from magazines in an attempt to seem ominous and anonymous, the missive threatens Augusto's girlfriend by revealing the existence of a pregnant mistress. As Augusto patiently reveals to his distraught lover, there is no pregnant girlfriend, no "other woman." There's only little sister Giulia trying to keep the family's sole breadwinner from having a life. Subtext to Augusto's revelation: you wouldn't believe my family. It's telling then that Augusto, the "normal" sibling, is least central to the story, and in some ways the least sympathetic. Within moments we are introduced to Giulia herself, and what an introduction!

Three shots, jump cuts between, and we zoom past her on a motorbike. She glances at the camera furtively and then laughs when two flirtatious bikers skid into the dirt and fly off their vehicle; played by Paola Pitagora, whose gorgeous, slightly gawky sensuality draws us like a magnet, Giulia is compulsively watchable. So is Lou Castel as Giulia's brother Alessandra or Ale, our (anti)hero who descends into the frame in a flash, landing on his feet from a tree perch, restlessly prowling the yard like a caged animal, snapping at his harmless nuisance of a brother. That's seemingly semi-retarded Leone (Pierluigi Troglio), who will later sigh, "What torture, living in this house." Ale is more ambiguous in his own lament - tediously reading the newspaper to his blind mother, he begins to concoct his own headlines. Eventually he moodily declares, "The king of England has died, leaving in darkest despair and desolation..." His mother cuts him off - "But there's still the queen." "Precisely," Ale says, and in his morbid mind the wheels begin to turn.

The Sunday Matinee

UPDATE: This post originally introduced the "Sunday Matinee" series. Its purpose was initially vague, but it evolved to cover three films each from four different sixties New Waves: Italian, British, Czechoslovakian, and French. The final entry in the British chapter ended up encompassing the whole "kitchen sink" movement while focusing on two particular films. The whole series can be found here.

Original intro

In the old Westerns, an outlaw will saunter up to the out-of-town gunslinger and give him an ultimatum: git out, or meet me at high noon. In a more benign fashion, consider this advance notice to Wonders readers: next week, at 12 pm East Coast time (4 pm by the site's numbers) on October 17, I will launch a new series, exclusive to Wonders in the Dark: "The Sunday Matinee." (The series was cross-posted in full on this site at a later date.) In it I will discuss a personal favorite from cinema history - for the most part these will be neither obvious masterpieces (those have been well-covered here; besides, I want to save many of these for my eventual "favorite great movies" canonical series, which is still on the horizon) nor total obscurities (also well-covered on the site). Most of the movies will be readily available (quite a few will probably belong to the Criterion Collection), usually from celebrated auteurs, and coming from my favorite periods in film history (the 30s through the 60s, with some 70s thrown in; definitely nothing post-1980 and probably no silents) as well as my favorite national cinemas (American, French, and Italian). These will be excellent films which really connect with me for some reason, and with only one possible exception, films which have not yet been discussed on Wonders in the Dark. The possible exception is next week's Fists in the Pocket, which may make a surprise appearance on the horror countdown (fingers crossed), but I will not be approaching at all from that genre's perspective so if anything, the piece will provide a nice complement.

Here are a few reasons for and ideas behind the series:

1) Why these films? One thing I love about this website is that it has introduced me to so many unseen movies; yet at the same time it's enriching to replenish ourselves at familiar hunting grounds. I was initially drawn to Wonders during the 60s countdown, and loved seeing unknown features alongside familiar classics, across a wide range of genres and styles. Since then, we've moved on to later eras and different channels of filmgoing, with more recent decade countdowns and the advent of genre explorations. I'm thrilled with both approaches, but admit that I also miss visiting and talking about what are, for me, the fundamental touchstones.

2) Why Sunday afternoon? This is a good question, particularly since weekends tend to be slow on blogs, and mornings are generally best to garner the most hits. I'll admit I have a sentimental attachment to the time slot - it makes me think of spreading out a Sunday newspaper in a sunny living room, wiling away a lazy Sunday by exploring its pages before going out to the beach, or for a walk, or whatever else (no errands, though). The obligation of church is over, the impetus to activity not yet arrived, and the afternoon stretches before you with the opportunity to both relax and stimulate your mind and imagination.

3) Why Wonders in the Dark? Ultimately I decided to center the series on Wonders. It seemed a natural fit, since there are so many classic-lovers here and since it was Dennis Polifroni who first drew my attention to that reading reviews/Sunday newspaper connection last summer, in a discussion surrounding my write-up on Jaws. (Dennis, though he likes to keep to the comments, once penned his own superb memory piece on Jaws and the cinema-going of his youth - one of the signature pieces in the Wonders pantheon; you've got to read it.) All in all, this seemed a natural fit. So I hope you can make some room for me on your own lazy Sundays; see you next week!

Read the comments on Wonders in the Dark, where this announcement was originally published.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)