This is an entry in The Sunday Matinee series.

Fists in the Pocket, Italy, 1965, dir. Marco Bellochio, starring Lou Castel, Paola Pitagora

Story: A restless, intermittently fitful young man seeks an escape - violent, if necessary - from his provincial villa and oppressive family.

Fists in the Pocket begins with a threatening note, but this j'accuse is just a bad joke. (Disturbing letters will recur throughout the movie, but the written word is an afterthought here; these characters, barbarians after a fashion, write their lives with their bodies and motions, not with mind or pen.) Composed in childlike fashion, words cut out from magazines in an attempt to seem ominous and anonymous, the missive threatens Augusto's girlfriend by revealing the existence of a pregnant mistress. As Augusto patiently reveals to his distraught lover, there is no pregnant girlfriend, no "other woman." There's only little sister Giulia trying to keep the family's sole breadwinner from having a life. Subtext to Augusto's revelation: you wouldn't believe my family. It's telling then that Augusto, the "normal" sibling, is least central to the story, and in some ways the least sympathetic. Within moments we are introduced to Giulia herself, and what an introduction!

Three shots, jump cuts between, and we zoom past her on a motorbike. She glances at the camera furtively and then laughs when two flirtatious bikers skid into the dirt and fly off their vehicle; played by Paola Pitagora, whose gorgeous, slightly gawky sensuality draws us like a magnet, Giulia is compulsively watchable. So is Lou Castel as Giulia's brother Alessandra or Ale, our (anti)hero who descends into the frame in a flash, landing on his feet from a tree perch, restlessly prowling the yard like a caged animal, snapping at his harmless nuisance of a brother. That's seemingly semi-retarded Leone (Pierluigi Troglio), who will later sigh, "What torture, living in this house." Ale is more ambiguous in his own lament - tediously reading the newspaper to his blind mother, he begins to concoct his own headlines. Eventually he moodily declares, "The king of England has died, leaving in darkest despair and desolation..." His mother cuts him off - "But there's still the queen." "Precisely," Ale says, and in his morbid mind the wheels begin to turn.

When I first saw Fists in the Pocket, I didn't know what it was or how it would turn out. From its earliest scenes, there's an uneasiness to the restless, impatient energy onscreen, manifested both in the lurching performance of Castel and the film's own aesthetic, filled with rumbling handheld shots, fluid but pushy camera movements, and cuts loaded with spatial and temporal ambiguity. We aren't sure if we're watching a tragedy or a black comedy, because what we see is often very funny. You are never quite certain where the film will go next - and this uncertainty puts you on the edge of your seat, allowing you to laugh, but simultaneously filling you with anxiety. If you haven't seen Fists in the Pocket, I'm happy I've lured you this far but consider perhaps "putting down" the review, availing yourself of the easy opportunities to catch this movie, and then returning here to ponder what you saw. Fists in the Pocket is a movie worth exploring without a guide - because it's about characters who explore life without guides, who indeed hastily dispose of their guides, and find themselves both lost and liberated.

Ale is filled with hostility for his home and family, but at first it's a comic hostility. He writes love letters to his sister, who only seems to find them amusing; he offers to kill himself and his siblings for his brother's convenience, and Augusto chuckles disbelievingly. We do too, because we recognize that even if the villa's atmosphere is claustrophobic, it is loaded with familiar comforts for Ale, a socially awkward youth who probably could not survive without this life support, both financial and psychological. Yet our laughter sticks in our throats; even if we think Fists holds nothing up its sleeve but black family comedy, threatening murder with false bravado, we know there's a possibility for the film to leap over that precipice. And leap it does - or fall rather, with a delicate poke; Ale lures his pathetic, hopeless mother to the edge of a cliff and, with a gentle push of his finger, lets her descend to her death. If this is upsetting, what we see next may be even more so - Ale filled with nonchalant disregard at the mother's funeral, resting his feet on her coffin and leaping back and forth over the corpse, crouching and stretching, doing exercises in the wake of a matricide which hardly required exertion. This was too much even for Luis Bunuel, who registered haughty disapproval at the film's irreverence.

Yet for many in the audience, we continue to be strung along. Castel is alarmingly charismatic and he and his sister form a kind of anarchic Bonnie and Clyde couple as they toss all their heirlooms, family portraits, and dusty old magazines into a bonfire, watching the past go up in flames and clapping their hands at the conflagration. This is why, no doubt, the film met with rapturous responses from young audiences in the mid-60s; on the eve of '68 its personal psychodrama had political implications, throwing off the dead weight of the past, barreling forward into the unknown, come what may. One of my favorite quotes of all time, loaded with a poignancy at once nostalgic and regretful, is in reference to this movie. Asked to explain his love for the film, French filmmaker and intellectual Jean-Pierre Gorin remarked wistfully, "for those who want to understand the sixties beyond the banalities that are ritually uttered about them, every scene of Fists in the Pocket, with the convulsive beauty of its framing and composition, amply proves how much this period was made by people so steeped in classical culture that they fantasized it could be solid beyond its fragility, shaking it to the core and ultimately ushering in a world they could themselves hardly live in."

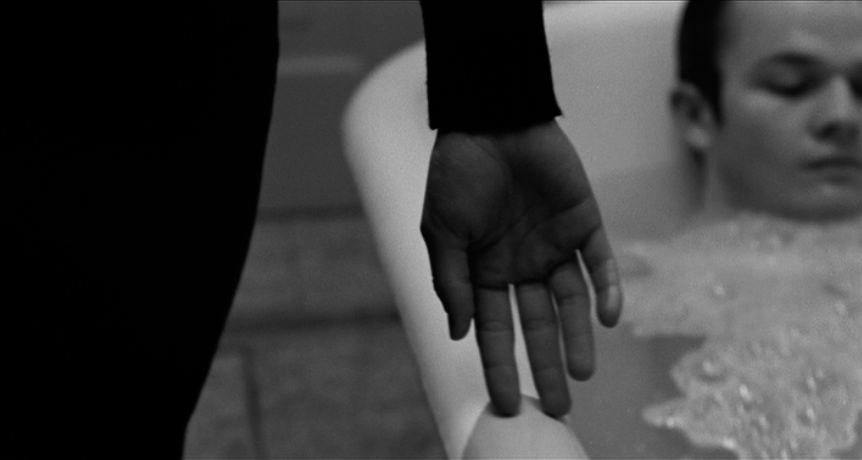

This is a perfect summation of the movie, for if Ale continues on his reckless path with gleeful abandon, the film and the other characters slowly detach themselves from his perspective, looking on in horror. What begins as the liberation impulse of an anarchist is eventually clarified as the self-realization of a fascist. Ale evokes our sympathy throughout the film with his awkwardness (despite his bravado), his occasional tenderness, his fierce charisma, and the fact that he seems so put-upon, so frustrated. But his true desire is not to free himself but to dominate others and by the end of the movie, when Ale collapses in a literally operatic fit which may be fatal, we have discovered what a monster our protagonist really is. Despite its provocations, Fists in the Pocket is ultimately a very moral film - and its moral awakening occurs when Ale drowns Leone in the bathtub. Poor, clumsy Leone, who haunts all the joyful, rebellious scenes like a forgotten conscience (he's never included in the siblings' playacting, and generally regarded as a family albatross) is Ale's shadow self, more epileptic, more bound to the villa and the family, more burdened by an unshakable humanity. So Ale kills him; Giulia, who more or less looked the other way at the matricide, is now forced to confront with true terror what her brother is capable of.

The true nature of the characters can be determined when they kiss their mother's corpse before the lid goes on the coffin. Augusto is, as always, the hypocrite, leaning in uncomfortably - knowing that he's glad she is gone so that he can move on with his life - and offering a quick peck on the forehead before moving away. Ale does not lie to himself but beneath his bravado is a coward; he leans forward and hovers over her without offering any kiss at all, though publicly his culpability is hidden. Leone, simple and sincere, weeps and kisses her without shame. And Giulia, confused in the wake of her brother's confession, glad to be free but filled with compassion for her dead parent, hesitates and then locks lips with the mother, crying as she does so. The scene is followed by the gleeful burning of the possessions which, in light of the film's murderous turn and the eugenic ferocity with which Ale destroys weaker relations, could take on the iconography of a book-burning - but most likely in the context of the narrative we dance along the flames with the characters, eager to see where we are headed next. We are headed to a dance, where we are reminded of Ale's insecurity and awkwardness. It's an uncomfortable scene in which we're touched by Ale's humanity and then reminded that he's gone too far - aware for the first time of the gravity of his offense, because now he no longer has the simple, human right to cry at a sock hop when no one will dance with him.

As always, the written word lends itself to narrative summary and analytical analysis, but this is not a film that theorizes, it's a film that embodies. Pier Paolo Pasolini compared it to Bernardo Bertolucci's Before the Revolution, calling Bertolucci's a "cinema of poetry" and Bellochio's a "cinema of prose." Bertolucci himself noted his own relation to the French New Wave with its playful use of the camera, while observing that Bellochio was drawn more to the English "Free Cinema" with its social consciousness and sense of concrete reality. But both cinemas - Bertolucci's and Bellochio's, poetry and prose, are cinemas of form and the film is just as much "about" its cinematographic restlessness, its elliptic cuts, its pulsating compositions, as it is about its themes or stories - or rather the two are inseparably connected. The editing is magnificently displacing - near the end, Ale playfully tugs his sister towards him and then we cut fluidly to a cat emerging from a hole in the wall and trotting over to the siblings, who are lying on the floor disheveled. Given what has just unfolded onscreen, we could have either witnessed the passage of a couple seconds or an hour - in which case the position of our characters is distinctively more unnerving.

So Bellochio maintains that vital sense of uncertainty, even after his story has determined its irrevocable direction and leapt over the precipice - like Wile E. Coyote, the movie knows that gravity will eventually prevail, but it refuses to look down until the last minute. Though certainly not optimistically radical, Fists in the Pocket is hardly conservative - Bellochio knows full well the hideousness of a hidebound existence, an ossified loyalty to values and icons long out of date, useless except in their ability to oppress. The director's understanding of the destructive impulse is palpable, even as he wonders if there's anything out there to fill the void. Even so, the portrait of ennui and claustrophobia is not without its lingering traces of sweetness, the sweetness "before the revolution" which Bertolucci celebrated in his earlier film. Fists in the Pocket takes place neither before nor after the revolution (in the sense of personal liberation), but while the psychological revolution unfolds - and the sweetness is mostly drowned out by bitterness. Yet as Ale lingers in bed on a lazy morning, as he stands on the balcony restlessly overlooking the wintry landscape, we know that the character is not dead to the world but rather all too alive and that as he kills the things which hold him back, he is only snapping his links to whatever sustained him in the first place.

The film concludes with Ale's hysterical epileptic seizure, not based on any medical case study, but rather a portrait of youthful frenzy reaching its breaking point, a descent into chaos at once terrifying and excruciatingly exciting. Ale writhes and twists on the floor, an operatic record blasting nearby, screaming and clutching his head in pain. Bellochio originally intended for Ale to survive the attack, but the editor wanted a more final conclusion and so the frame freezes as the young man gasps, appearing to give up the ghost once and for all. Either way, the moment has a musical finality - whether or not Ale survives, his frenetic symphony has reached its inevitable conclusion. The musical analogy is correct - whatever the film's outlook (and this is not a movie which lies to us to make horror more palatable) we are not carried along intellectually or morally, but as if by the force of great music, unquestioning, embracing the flow of images and sensations - glorying in that last bit of life before all goes dark and silence reigns again.

To view more images from the film, visit Shaking the Foundations: A Visual Tribute to Fists in the Pocket

Read the comments on Wonders in the Dark, where this review was originally published.

No comments:

Post a Comment