for the introduction & line-up of monthly capsules

running from August 2021 to February 2022

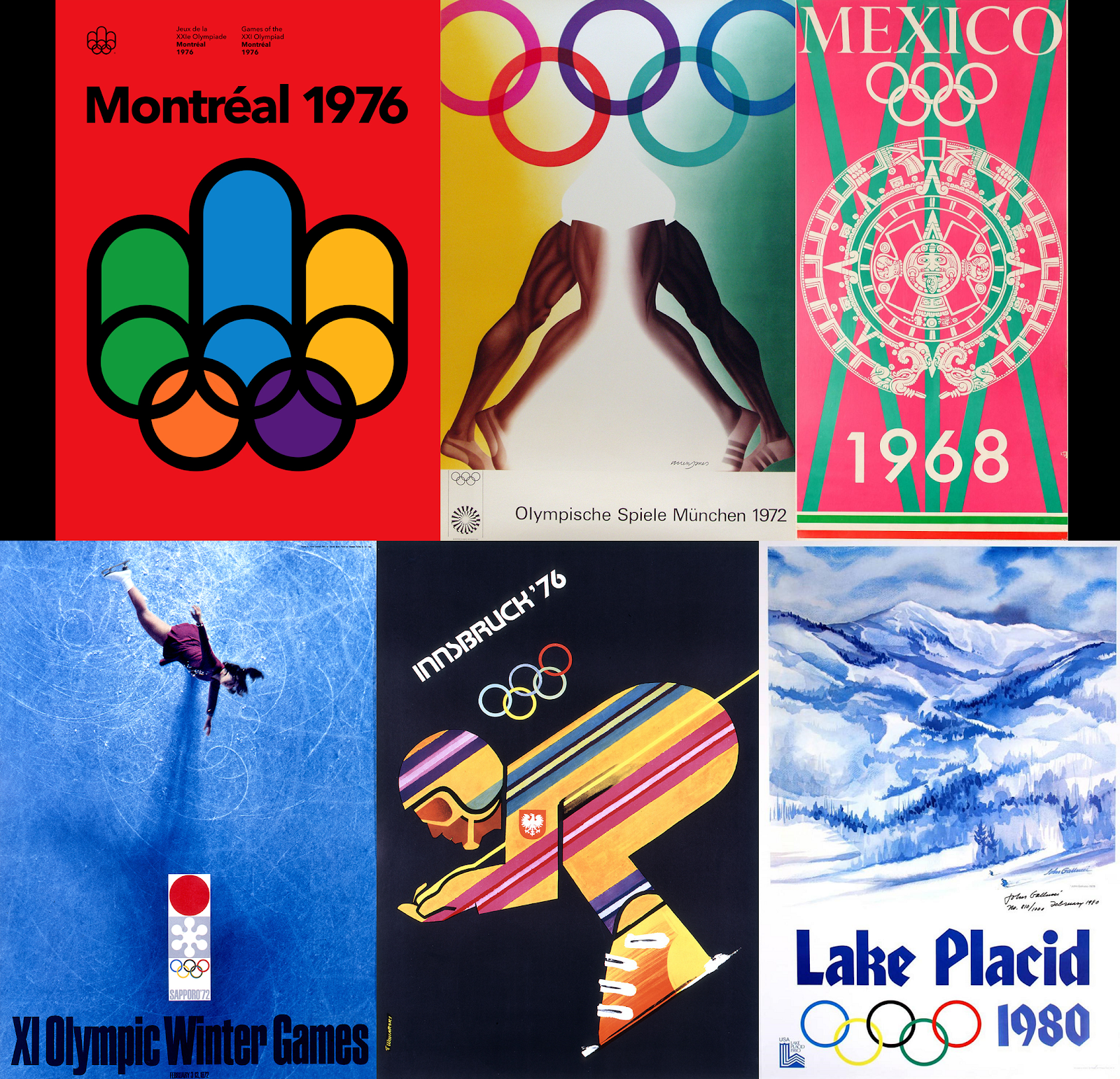

Sapporo Winter Olympics, dir. Masahiro Shinoda

Winter 1972 - Sapporo, Japan

Fifty years ago, the world descended upon a northern Japanese city of a million inhabitants founded just a century earlier and most famous to Westerners for its beer (today, Sapporo is bidding to bring the Olympics back in 2030). At this time, twenty-seven years after the end of World War II, Emperor Hirohito himself was still around to open the games; in a montage of journalists' quarters, we briefly glimpse a news clipping, a photo from what appears to be Pearl Harbor...or perhaps a later Naval battle that went the other way. As with previous winter documentaries, and even the summer '88 Seoul films, memories of war contrast with the cheerful hodgepodge of world travelers navigating the host city - in this case, an intriguing combination of remote wilderness and urban sprawl. The spectacular closing shot, which begins by hovering over one of the now-empty mountains and slowly pulls back to reveal the entire vast metropolis backed by a range of peaks under a twilit sky, is a poignant God's eye view of the full picture (after two and a half hours of selective perspectives). It's also yet another stunning use of the widescreen frame - this is the first Olympic film I've seen that was shot in CinemaScope, and it's one of the most formally striking documentaries of the entire collection. Shinoda was a leading light of the Japanese New Wave (Double Suicide, Pale Flower), and he brings a particular sensibility to Sapporo - as modern as the work of Claude Lelouch in 1968's 13 Days in France, but more interested in crisp, sharply defined shapes and colors than the woozy blur of Grenoble.

Weather is an issue once again, with flurries of snow enveloping some of the competitors and the bitter cold creating icicles in cross-country skiers' hair and turning the slalom racers' faces a raw red, but much of the footage unfolds under clear if chilly skies, adding to the sense of distinction between visual elements. Once again, as with the '56 Italian film, I'm struck by how black and white seemed so perfectly suited to winter sports...until you see these events in such rich, bold color, the bright primaries of the slalom flags, stocking hats and parkas dotting these snow-packed landscapes like abstract dabs and dashes of paint across a white canvas. And while he's given to precision in his deployment, Shinoda can also get impressionistic at times, like when he overlays shots of gliding and soaring swans across a single long take of the bubbly, mopheaded figure skater Janet Lynn, who stumbles and falls early in her routine yet gets right back up and finishes strong (for an offscreen bronze although the performance is its own reward in this depiction). Sapporo is not just about the image, however. Audio is also an important formal element; the film deploys disconnected dialogue, crowd, and equipment noises alongside musical flourishes in Godardian stop-and-go fashion on the soundtrack. And it uses these aesthetic choices in conjunction with a curiosity about the men and women in amateur competition, who relish these brief grasps at eternity before returning to the mundane workaday world.

One of the most captivating sequences captures those athletes deeply immersed in their work: as the narrator describes slalom as a musical composition that must be played seamlessly, with each flag as an individual note, we see a montage of the skiers standing still with their eyes closed, mumbling to themselves, their hands weaving side to side just inches from their faces. Gloves clenched tightly to their poles, they navigating the course in advance - indeed, much like a conductor memorizing their score. The movie's tempo balances fast and slow, chaotic and contemplative, hurling itself into the crowd of journalists bombarding the arriving athletes with trivial questions and narrating the controversial ban on Austrian skier Karl Schranz for dancing to close the borderline of professional promotions. The IOC's draconian action nearly derailed the Olympics, and Shinoda's brief coverage of the fallout represents a rare interlude of worldly reportage amidst the film's more immersive qualities. Sapporo pays particular attention to the mindsets of athletes, conducting interviews that unfold over the footage of them before, during, and after their events. The glory of Japan's medal sweep in the medium ski jump is later followed up with the bitter disappointment of Japan failing to place in the longer event (the camera follows one frustrated competitor for several minutes as he trudges out of the landing area, after depicting his struggling leap in excruciating slow motion).

This theme is most evident in the depiction of Keiichi Suzuki who, as revealed in series of brutally straightforward titles (overlaid as he unlaces his footwear following his farewell race) placed first over and over in international competitions throughout the sixties but never once broke into top contention in his three Winter Olympics. In this '72 attempt he wound up all the way back at nineteenth. Only twenty-nine years old, the film catches him looking back over a career that began when he was six. In a sad, wistful voiceover, he tells us that he managed to hang onto hope against all reason before his "death" in Sapparo. Now he's ready to be "re-born" into a new existence, after living and losing that Olympic dream one last, bittersweet time.

Games of the XXI Olympiad, dir. Jean-Claude Labrecque, Jean Beaudin, Marcel Carriere & Georges Dufaux

Summer 1976 - Montreal, Quebec (Canada)

As depicted in this French-narrated documentary, the Montreal event was something close to the calm in the middle of the sixties/seventies/eighties Summer Olympics storm; '76 lacked the massive superpower boycotts of '80 and '84 and the the notorious political disruptions of '68 and '72. The games were most notable for their athletic breakthroughs rather than any off-field context, although there was still an unprecedented boycott by many African nations, based on how the IOC had handled an issue with South Africa (it refused to ban the New Zealand national team for touring the sanctioned apartheid state). This is referenced only glancingly in the film: we overhear voices discussing the effect on athletes whose countries are pulling out, over a shot of someone packaging or removing a credentials badge. Without already knowing the larger context, we probably wouldn't be able to determine what they're talking about. Nonetheless, the film prizes such overheard snatches of conversation for their own sakes, as part of its fly-on-the-wall aesthetic. The most memorable examples involve the Soviet gymnast Nellie Kim. In one sequence, a classic pulling-back-the-curtain cinema verite moment, we're positioned behind a TV camera as an announcer tries to navigate the language barrier with Kim, moving her around and roping in a reluctant translator to make the conversation go more smoothly. Later Kim gets into an argument with her coach near a phone booth, as the sound and camera crew capture their colorful disagreement from a few feet away. One of the four directors of this film, Dufaux, collaborated with Pierre Bernier on another documentary solely focused on Kim and one gets the sense that Games is either sampling or teasing that side project here. It's a striking moment given that Olympic documentaries usually feel a bit more stage-managed and/or artistically packaged.

Various gymnasts' fluid rise and fall (careerwise, but also literally) is placed at the center of the movie, which - amidst the loose cutting - does have a kind of three-act structure. (We'll get to third act in a bit, but the first follows the young Hungarian team in the equestrian/swimming/shooting/fencing/cross-country pentathlon, amidst many other cutaways.) In addition to Kim's perpetually bemused expression, Games focuses on a distressed-looking Olga Korbut watching the rise of new rivals. An international superstar for much of the seventies, she'll be retired by 1980 - despite her diminutive, youthful appearance, Korbut is already older than much of the competition at twenty-two. In addition to Korbut's teammate Kim, a fourteen-year-old Romanian newcomer is emerging. As the narrator informs us, "It is the end of Olga Korbut's reign, and the beginning of Nadia Comanechi's." In his at-best ambivalent description of the documentary, Cowie describes the film's handling of the gymnastics competition as "bizarre" for its too-rushed air and emphasis on the discomfort of the competitors. Comanechi at least looks jubilant, beaming as she receives a gold medal (although within a year she would shoot up another seven inches and attempt suicide). Both Kim and Comanechi would receive perfect tens in particular events, an achievement so rare that the scoreboard had to shown "1.00" to represent it. When Wide World of Sports showed a montage of her routines, they scored it with a piece of music that ended up on the pop charts as "Nadia's Theme"...even though it had been written for the feature film Bless the Children and was already being used as the opening music for the soap opera The Young and the Restless. Ironically, Comanechi never performed to this music until 1996, when she and her new husband (the American gymnast and coach Bart Conner) were featured together in an episode of Touched by an Angel.

The biggest star in Games, however, is an American. The three Olympic gold medalists who loom largest over U.S. athletic history are probably Jesse Owens, Muhammad Ali, and Caitlyn Jenner. All of them are known, at this point, as much for their groundbreaking social significance as their athletic accomplishments (although for Owens, the two went hand in hand); indeed, both Ali and Jenner won their medals and achieved fame under different names (and, in Jenner's case, with a radically different appearance and gender presentation). In a film that's often quite cavalier about the details of competition, the decathlon is depicted with crystalline clarity, the coverage organized event by event as narration and snatches of announcers' commentary lay out the stakes. Of course by the final race those stakes have been more or less resolved, with Jenner's triumph all but guaranteed thanks to outstanding performances in the rest of the "best all-around athlete" tests. The champion's wife curses out the journalists and officials crowding around her until Jenner arrives to reach into the stands and they embrace: another impromptu human moment captured by filmmakers on the hunt for such stuff. (There's a similar weeping-wife-watching dynamic on display in Greenspan's L.A. film, although far more work is put into building it up via interviews and narration - a testament to the different sensibilities at work in the two documentaries.) Jenner would later recall looking in the mirror the next day, wearing nothing but this gold medal and wondering, "What the hell am I going to do now?" As with Comanechi (and many other Olympians, to be sure), a future of lonely confusion - despite the pop culture tributes and the cheering crowds - stretched out into the distance before her.

We might as well end where this Montreal documentary begins: a snowy scene of the Olympic Stadium being constructed in the dead of winter, a remarkable contrast with the warm season when athletes and spectators would arrive here from around the world. What else was going on at this early date, before the Olympics? Well...the (other) Olympics, actually. For the last time in these round-ups, we're rewinding the clock in order to reach the winter games, but this time only by a few months. Initially (and eventually) this series separated the two seasons of Olympics by a century, but as we reach our halfway point it's time to meet again in 1976.

White Rock, dir. Tony Maylam

Winter 1976 - Innsbruck, Austria

The movie opens unusually for this series, with close-ups of gloves, boots, a helmet - and a profile of someone who looks familiar. But...it can't be him? Right? The man steps into the back of a four-person bobsled and the camera remains fixed to the front, facing back at the four passengers for the entire ride. We've seen shots like this in previous winter documentaries, but usually just for a few seconds with shakiness and quick cutaways emphasizing the speed and technical difficulty of the photography. In this case, however, the frame remains fixed and the angle is wide enough to capture the landscape in the background, and the shape of the overall course as we take each turn: cinema as a precisely executed thrill ride. It's a stunning achievement; Peter Cowie's text informs us that the entire camera was destroyed by the g-forces, aside from the Panavision lens which somehow survived intact. As the drivers exit, that first man remains behind and removes his helmet, speaking to directly to us. It's unmistakable. This is indeed James Coburn, Hollywood star, our guide through what is certainly the most unusual Olympic film I've watched yet. (Only the '48 film, with the narrator fretting about his wife, could compete - and that conceit is a lot less ambitious than this one.)

Coburn presents himself as an adventurous tough guy who's humble enough to admire the prowess of athletes who can go much further. He exhibits the wisdom that comes with age (his chiseled features and gray hair make him look a bit older than his forty-seven years) but also some of its weariness and respect for the vigor of youth. He is willing to try anything - well, almost anything; he pointedly remarks that his fear of falling is greater than his desire to fly (so no ski jump) and after another long shot traveling down the course on a single-person luge, he appears in the frame to greet the rider and then turns to us quizzically and says, "You didn't really think that was me on there...did you?" But he does suit up as a goalie to block lightning-fast hockey pucks and he treks through the snow on skis before firing his rifle at targets (scrupulously noting that in the real biathlon, they have to go much further before testing their precision). There's even a sequence in which he waxes his downhill skis with a special formula which he's careful to hid from the viewer. As a result of Coburn's personable, familiar demeanor, and his careful I-know-how-to-explain-things-to-the-masses approach, a lot of the information - which might otherwise go over our heads - sinks in. This is one of the most educational, as well as entertaining, Olympic films.

It's also one of the shorter entries in the collection, just an hour and seventeen minutes, so it sacrifices comprehensive coverage for stylistic punch. The fact that Coburn is delivering scripted narration additionally makes it feel as if we're watching a carefully planned production rather than the unfolding of an unpredictable live event, but there are a few spaces carved out for the tension of competition. The conclusive match between the USSR and Czechoslovakia is delivered blow by blow and White Rock does not hide its disappointment at Soviet victory. In figure skating, Coburn/Maylam carefully distinguish between the crowd-pleasing qualities of the American teenagers Tai Babilonia and Randy Gardner, on the one hand, and the cold but technically exquisite athleticism of Soviet victors Irina Rodnina and Alexander Zaitsev. Not much attention is paid to the surrounding context of these games, either historical or geographic, especially when compared to Shinoda's survey of Sapporo. However, it's worth noting that our return to Innsbruck, in such a different format than '64, marks the second time we've re-visited a familiar Olympic location over two different winters since '28 and '48 were both held in St. Moritz.

The approach to this film was so unique that it spawned several further success stories. The soundtrack became a bestseller and White Rock transformed or boosted the careers of Mylam (a documentarian who transitioned into fiction films) and director of photography Arthur Wooster (who'd already shot the innovative Downhill Racer and worked on previous Olympic films, including the summer one we're about to cover). There are many shots like that opening one, either facing back at the athlete with the landscape unfolding behind them or from the athletes' perspective: racing down a hill (or, incredibly, off a jump), skating around a rink, or swerving through a course, often in extended montages scored to a pounding electronic score by Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman. This must be a hell of an experience on the big screen. And, as in Sapporo Winter Olympics, the film's expansive 'Scope and precise, sharp color gives it the feel of an epic narrative feature rather than the more raw, off-the-cuff aesthetic we usually associate with documentaries. The summer docs of this time much more readily embrace that traditional documentary looseness than do the winter ones, interestingly enough. For an example of both fly-on-the-wall casualness and cinematic experimentation, we're finally going to let the seasons switch places chronologically. For the first time moving back instead of forward in order to reach the summer.

Visions of Eight, dir. Milos Forman, Kon Ichikawa, Claude Lelouch, Yuri Ozerov, Arthur Penn, Michael Pfleghar, John Schlesinger & Mai Zetterling

Summer 1972 - Munich, West Germany

As if splintered into pieces by the bullets of Black September, the '72 Olympics is presented to us in fragments. This is true not only between the eight distinct short films in this anthology but also often within these sequences. Perhaps the best of these pieces (and among the most indicative of that fragmented approach) is Kon Ichikawa's "The Fragments" which applies a structuralist vision to the 100-meter dash, replaying the entire race over and over in slow motion, each time singling out a different runner. The spare narration carefully amplifies the mystery of what we're watching, inspiring further questions without resolving the ambiguity that the otherwise silent images evoke. We are not watching the runner's feet, we're observing their faces - pondering what this experience is like and realizing they themselves can't quite explain the inside of this brief eternity. I'm reminded of how quantum physics suggests that the appearance of physical reality's solidity only applies at a certain distance; as we move closer to the particle level (forgive me if I'm mangling this), Heisenberg's uncertainty principle becomes more relevant. Watching a race at full speed, we find ourselves wondering what exactly gives one runner the edge over another, physically and mentally, but we may feel we have some grasp on the overall flow of action. That grasp slips away when we isolate, delineate, and take our time investigating the individual components. Clarity, it seems, is an illusion that breaks down, rather than emerges, upon a closer look.

Arthur Penn's "The Highest" also uses avant-garde techniques to break down and isolate pole-vaulters although this effect is more aesthetic than conceptual. Edited by the legendary Dede Allen, the sequence begins in complete abstraction, slow-motion blurs pulsating in shot after shot, and then slowly brings the athletes into focus as they rise, bending themselves and their instruments in gravity-defying exertions. Sound is used primarily for punctuation. Milos Forman's "The Decathlon" uses sound - music, specifically - as wry commentary on an event that is already helpfully divided into neat segments. He scores each event with a form of German folk music in keeping with the Munich games' determination to evoke non-Nazi forms of cultural celebration (Peter Cowie notes that Forman, an orphan of the Holocaust, may have been mocking the West German government's historical choices). With his characteristic eye for faltering, absurd, bemusing and bemused humanity, the Firemen's Ball and One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest filmmaker shoots musicians in traditional dress yodeling and clanking cowbells, intercutting (or undercutting) the sprints, throws, and leaps of the decathletes until finally Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" lends the final event some aural dignity. Yet here too there is subversion, as Forman accompanies the triumphant symphony with a rapid montage of runners collapsing in utter exhaustion, rolling around on the track and even smothering one another - conjoined by competition.

Claude Lelouch takes that ironic vision of Olympic non-glory to its logical conclusion, centering his entire segment "The Losers" on...well, you get the idea. This will be hard to watch for anyone who has ever cringed at cameras being shoved into the face of a devastated competitor who came up short, but it's also rewarding because the longer we linger, the more our immersion into these expressions of raw outrage and despair feel compassionate rather than exploitative. Lelouch's film also ends with athletes leaning on one another but in this case, we witness a conscious display of compassionate solidarity rather than just sheer exhaustion. Like Lelouch, Yuri Ozerov isolates a single moment of each event for conceptual study, although he goes in the opposite direction, capturing that last instance of nervous, excited anticipation before the starting gun or whistle. His "The Beginning" appropriately opens Visions of Eight after an introductory scrawl, explanatory narration, and depiction of the stadium filling for the opening ceremony. Placed next is Mai Zetterling's "The Strongest", which couples images of strongmen struggling with their barbells alongside an overwhelming catalog of the kilograms of food consumed in the Olympic village (read in a clipped Teutonic accent). Noting that she's not interested in sports but is quite interested in obsession, Zetterling offers her astonishment at Olympic insanity, in the form of mass organizing as well as athletic exertion. She's both appreciative and incredulous. That she's the only female director on the project makes her piece - especially given its hypermasculine focus - an interesting companion to one which comes a bit later.

Michael Pfleghar's "The Women" is keen to express admiration - if also, several critics have observed, some patronization - for the increasing involvement of females in the games, most notably centering a lyrical passage on the preparation, contemplation, and execution of Soviet gymnast Ludmilla Turishcheva's routine. She won three golds in this Olympics but was overshadowed in the public imagination by her younger teammate Olga Korbut. Curiously, Korbut appears to be entirely absent from this or any other sequence, meaning that those past-her-prime glimpses shown in the Montreal documentary will be her only presence in this whole series (many viewers will also be surprised to miss record-setting swimmer Mike Spitz, who won seven gold medals in '72 - unsurpassed until Michael Phelps' '08 haul). On the other hand, "The Women" does have a treat for those of us traveling back in time for these round-ups: we get to witness the emergence of Ulrike Meyfarth, whom we last saw a dozen years down the road, triumphing in the high jump at the close of her career in Los Angeles. An adolescent with very seventies helmet hair (vs. her more feathered eighties mullet), she presents yet another marker in the long Olympic passage of time.

Each of these chapters is introduced by a black-and-white montage of photographs depicting the director at work, as their voiceover lays out their particular interests. The project was organized by David Wolper, who encouraged the filmmakers to focus on different facets of the games and choose their own crew (many other big names, like Federico Fellini and Francois Truffaut, were also approached but declined). At one point, Visions of Eight was supposed to be Visions of Nine (and, before that, Visions of Ten until Franco Zefferelli dropped out) but for whatever reason - sources are unclear - Ousmane Sembene's footage of the Senegalese basketball team was cut from the film, an unfortunate loss. So with seven already discussed, this leaves only John Schlesinger's "The Longest". I haven't been outlining these segments in order but it does make sense to end my coverage with the work that ends the film itself. "The Longest" follows British marathoner Frank Shorter on his, well, long odyssey both to and within the Olympics. This is the only part of the movie - aside from an oblique allusion in the opening narration - to acknowledge what most people now remember about the 1972 Olympic Summer Games in Munich.

Early in the morning of September 5, eight members of the group Black September snuck into Israeli athletic quarters in the Olympic Village, murdering two athletes and taking nine hostage. A tense standoff emerged for the next two days, as the games were shut down (eventually, after continuing for several hours in the morning) and negotiations began. The Palestinian terrorists demanded the release of over two hundred prisoners in Israel as well as of the eponymous leaders of the West German left-wing Baader-Meinhof gang (Red Army Faction). The Israeli government refused to negotiate, leaving an extremely haphazard German operation to extend negotiations and eventually agree to a flight out of a NATO base. German police bungled the entire operation, which was supposed to be a set-up to rescue the athletes before any departure, leaving Black September gunmen to shoot all the hostages before throwing grenades into the helicopters where they were tied up. (Over the subsequent decades, Mossad would authorize assassinations of many involved in planning the kidnapping, and some who weren't - I've written about this in my review of Steven Spielberg's 2006 film Munich). The rescue mission was initially announced as a success before Jim McKay was forced to deliver to one of the most infamous news commentaries of all time, up there with Walter Cronkite removing his glasses after getting an update from Dallas:

"We just got the final word...you know, when I was a kid, my father used to say 'Our greatest hopes and our worst fears are seldom realized. Our worst fears have been realized tonight. They've now said that there were eleven hostages. Two were killed in the rooms yesterday morning, nine were killed at the airport tonight. They're all gone."

None of these details are presented explicitly in "The Longest"; instead, Schlesinger relies on haunting, fleeting images of crowds and cameras gathered around the Village, headlines, TV footage, photos, the burnt helicopter, flowers poignantly placed in tribute, and, of course, one of the stocking-masked Black September members leaning out over a balcony: an iconic image of the tumultuous, terror-ridden seventies. Shorter's comments on the massacre are brutally frank about a world-class athlete's prerogative; he feels he must focus on his own purpose in Munich and block everything else out as a distraction. (My father and aunt, watching the film with me, were deeply unimpressed and dubbed Shorter a sociopath and/or narcissist.) There is a sense of grim finality to the closing sequence, of acid-laced irony but also weary respect, first in the juxtaposition of the marathon race with the shock and anxiety surrounding the hostages, and through the contradictions of the closing ceremony itself, as medals are rewarded, speeches are given, and marathoners still straggle into the stadium amidst the revelry. They're unable to follow the feel-good script in an Olympics forever marred by the intrusion of the outside world into the idealistic fantasy of a peaceful international community, one which proves unsustainable even for these few short weeks as summer slides toward autumn (the torch was extinguished on September 11, 1972).

Olympic Spirit, dir. Drummond Challis & Tony Maylam

Winter 1980 - Lake Placid, New York (USA)

For the second time, the Winter Olympics were held at Lake Placid and for the second time, there's no official film to commemorate the result. Unlike for 1932, however, I don't have to turn to newsreels on YouTube as compensation because the Criterion Collection provides a substitute in its boxset. Olympic Spirit is, essentially, a long-form music video and something of a commercial (opening and closing titles promote Coca-Cola, who helped fund this assembly of footage, and the filmmakers make sure to include a shot of a girl's hat emblazoned with the Coke logo). White Rock's Maylam is behind the camera once again, so elements like extreme point-of-view shots and wall-to-wall electronic rock are at the forefront. This time there's no James Coburn guiding us along, explaining technique and pointing out particular athletes (who go nameless here, a great rarity). We're left to our own devices, enjoying the fast-paced cutting to music and not worrying about what any of it all "means." This is the most purely aestheticized Olympic film I've watched, and the shortest as well: just twenty-seven minutes long. Nonetheless, it manages to hit a number of marks along the way. The torch is lit; ski jumping, downhill skiing, figure skating, speed skating, bobsledding, and hockey (of course, as we'll get to in a moment) are all featured; and a little girl skates across a lake serves to embody the stubbornly innocent spirit of the games. Not just the director's conceit, she later re-appears for the official closing ceremony.

The most striking sequence in Olympic Spirit presents the ski jumping. Even with all of the innovations we've seen in previous works, this may be the most arresting footage so far, especially when a camera is mounted to a ski to capture not just the tips soaring over the snow but also the body of the skier himself leaning into frame overhead. (I wanted to use this screenshot but it was too difficult to find; I was lucky to dig up the hockey match from this great piece on a husband-and-wife site devoted to both cooking and Olympic films.) The physical constructions of the jumps themselves are captured in awesome, terrifying fashion: towers looming over the frozen lake like craggy mountains housing the villain in a Disney fantasy. Never have these structures seemed so narrow and fragile...or steep, though that's probably just an optical illusion. And Olympic Spirit features the worst crash I've ever seen (there have been a lot so far) when a jumper completely loses control of his position mid-air and smashes into the ground on his back. Cutaways show other skiers, implicitly - though probably not actually - at this same moment, glancing to their side and quickly turning away with a grimace.

Of course the dramatic centerpiece of the 1980 production is, as it must be, hockey's "miracle on ice" in which scrappy American underdogs defeated the Soviet juggernauts (they still had another match to go before winning the gold but this was the encounter of legend). The British crew captures the colorful, eccentrically all-American crowd both around of the stadium and in the stands, with a giant placard depicting Uncle Sam giving a big Russian bear the boot. The emphasis inside the rink is on collisions in which the U.S. players batters the USSR mercilessly, with an implicit level national fury that always seems to bubble up in hockey. Previous documentaries matched the Czechs against the Soviets soon after the Prague Spring was put down, always with disappointing results. When the tying and winning goals are achieved, the hometown crowd bursts into an overwhelming cascade of feverish patriotism (singing, flag-waving, chanting "U-S-A") which many observers marked as the beginning of a national "comeback" after the dispirited decade of Vietnam, Watergate, gas crises, stagflation, and malaise. The Soviets look on incomprehensibly, ominously forecasting further humiliation that year, when America would lead a boycott of their summer games in Moscow.

The Olympics in Mexico, dir. Alberto Isaac

Summer 1968 - Mexico City, Mexico

Indeed, this Olympics was touched by recent political events in other countries as well. While there is no mention of Tlatelolco in Isaac's film, he does feature the most iconic image to emerge from '68 and arguably any Olympics ever: during the national anthem at the medals ceremony, 200m gold and bronze medalists Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists, a gesture associated with the "black power" movement. Although U.S. Olympic officials initially defended them, they were forced to leave the delegation and Olympic Village. The documentary does show other athletes making a similar gesture (and wearing berets associated with the Black Panthers) - perhaps unpunished due to their timing, since the raise the fists before the anthem rather than during. IOC President Avery Brundage's decision to punish these two for their "domestic political statements" came under particular fire because Brundage had no such objections to Nazi salutes in the '36 Olympics, when he was a U.S. Olympic official pushing hard against any potential boycott of Hitler's regime. Incredibly, Brundage leaned into this comparison by arguing that those salutes had been acceptable because they were national. An alleged anti-Semite and Nazi sympathizer, Brundage would meet with controversy again in '72 - the last time he oversaw the Olympics - when he was accused as trivializing the murder of Israeli athletes by insisting that "the games must go on."

Another, quieter protest would have even more dire long-term consequences for Czechoslovakian gymnast Vera Caslavska, who turned her head away when the Soviet anthem was played. This was mere months after the country had been invaded by the USSR to suppress a liberalizing administration. Isaac shows her routines but if he included a shot of her protest (and he very well may have) I was not looking for it at the time and must have missed it. He does cut almost immediately from her athletic achievements to her wedding in Mexico City, a choice of venue that (in addition to her skill and defiance) endeared her to the local population. Back in her home country, unfortunately, she faced severe repression - unable to compete, travel, or even have much of a public presence until the Velvet Revolution overthrew the Soviet-sympathizing government a couple decades later. If Isaac's film goes light on all the politics I've discussed here, he is still quite interested in the larger cultural context of this Olympiad. Following the Olympic torch from its usual ignition in the ancient Greek Temple of Hera along a route which eventually traces Christopher Columbus' journey from Italy to Spain to the New World, Isaac also makes sure to capture the lighting of a cauldron atop an ancient Teotihuacan Temple of the Moon at night, one of many vivid, colorful images in the movie. When the torch reaches its final destination in the stadium, it is carried by Mexican hurdler Enriqueta Basilo - the first woman to complete a torch relay.

Elsewhere in the film, Isaac surveys the arts-heavy events scheduled throughout the year, featuring artifacts and dignitaries from all over the globe. His eye is particularly keen when it comes to the striking architecture of the city and the games, bold fusions of high modernism and indigenous cultures decorating the crowded landscape. The film itself displays a rich, deep colorfulness in its texture. Some of the evening photography is particularly beautiful, with gorgeously blue twilit skies crowning the athletes and spectators inside the stadium. Like the seventies winter films, but unlike the summer ones, The Olympics in Mexico is presented in a wide aspect ratio. Another interesting point of contrast with later and elder documentaries is captured rather than chosen by Isaac: the fashion. Many women sport short haircuts and while the men's hair is "long" by fifties standards - meaning a few inches more around the edges and on top - it's not actually, you know, long. These are jocks, not hippies, and while the era is peak sixties, the touchstones of the counterculture remained quite "counter," only crossing over into mainstream hegemony a few years later. But the energy of youth is evident everywhere, the restless, explosive zeitgeist and brightly decorated, sweltering locale working as perfect complements.

Structurally, the film is most interested in capturing as wide a range of sporting events as possible, so we don't spend a lot of time lingering on the athletes in a personal manner. The cameras treat them as subjects to observe rather than interview. (In one tasteless sequence, a montage of female derrieres punctuated by comical musical cues, that observation becomes a little too leering.) Isaac is also excessively fond of slow motion, drawing out most of the races and many of the other competitions, which tends to dilute the technique's effectiveness and extend an already lengthy runtime although it does also result in numerous striking shots. This is perhaps most evident during the equestrian passage, a riveting yet hard-to-watch sequence that underscores how dangerous the course can be for the riders (not to mention the horses). Isaac may be the only Olympic filmmaker who was also an Olympian himself, competing as a swimmer in '48 and '52. This special understanding of what it feels like to perform under these conditions is best manifested during his coverage of the marathon. Isaac, of course, captures the victorious Ethiopian Mamo Wolde and his victory lap following the record time. But he seems more interested in the last-place finish of John Akhwari. Cramped and injured along his run (he's seen limping at times on a bandaged leg), the Tanzanian must frequently stop and resume if he does not want to drop out. Arriving at the stadium when it's pitch black outside, Akhwari finally staggers across the finish line hours after the winner. If not the symbol of meteoric revolution that those times so desperately wanted, he remains a symbol of determined, defiant endurance that all times need.

Having crossed the stream in 1976, next week's entry will continue through the sixties and fifties with the Summer Olympics (Tokyo 1964, Rome 1960, Melbourne 1956, and equestrian events held separately in Stockholm that same year) and the eighties and nineties with the Winter Olympics (Sarajevo 1984, Calgary 1988, Albertville 1992, and Lillehammer 1994).

No comments:

Post a Comment