for the introduction & line-up of monthly capsules

running from August 2021 to February 2022

Where the World Meets, dir. Hannu Leminen

Gold and Glory, dir. Hannu Leminen

Memories of the Olympic Summer of 1952, dir. Holger Harrivirta

Summer 1952 - Helsinki, Finland

Moving back through time with the summer games, we're reaching a point where the impact of World War II can be felt more directly. Many of these athletes were veterans of a conflict that ended just seven years earlier, and the host country was itself directly involved in that conflict. In fact, Finland's longtime desire to host the Olympics was intertwined with the outbreak of war. Remarkably, long before they were allied in combat - or even run by the leaders who took them to war - the capital cities of all three Axis Powers were scheduled for three successive Olympics: Berlin in '36, Tokyo in '40, Rome in '44 (the winter games were also scheduled for those countries). Even before Hitler invaded Poland, the Japanese war with China necessitated a change of venue and so Helsinki, long prepared for such a prospect, was happily volunteered as a replacement. But when the "Winter War" began between the Finns and Soviets, they too were forced to withdraw. A dozen years after that aborted opportunity, Helsinki finally got its chance to host under unusual circumstances. Perhaps the most significant aspects of this particular Olympics were the returns of Japan and a united German team after their '48 ban and the debut of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics; the last time the country had participated was 1912, when it was still officially the czarist Russian Empire. Considering that the Soviets had invaded Finland and the Finns later teamed up with the Germans to drive them out (refusing to call themselves allies, although Hitler saw them as such), one might expect a frosty reception for the former belligerents. Instead, if the narrator of Where the World Meets is to be believed, these first-time Soviet Olympians were greeted with enthusiastic applause.

With the Cold War in full swing, these documentaries - a black-and-white two-parter and a shorter color film - capture a spirit of international camaraderie and friendly competition alongside a bittersweet, even bemused sense of disappointment. The Finns were so hungry for Olympic glory that the gray, rainy weather accompanying the opening ceremony became a sore subject. (Tourists stayed away, Memories of Olympic Summer tells us, and Finns from outside the city assumed there wouldn't be available tickets - although the stadium looks packed to me.) Also surprising was the Finns' extremely underwhelming performance in "athletics" (as the track and field events are officially dubbed) after years of domination; a bronze for the javelin was their only medal. Where the World Meets focuses exclusively on those competitions, never leaving the stadium aside from the magnificent opening torch relay across fields and hills and, eventually, the memorable marathon around the streets of Helsinki. By contrast, Gold and Glory (part two of the official film) travels throughout the city for various non-track/field sports like swimming, diving, equestrian, wrestling, weightlifting, and gymnastics. Here the Finns made up for their medal deficit from the main arena, winning gold in boxing and boating among other disciplines. All of this is captured in striking black and white, facilitating bold compositions and closer camera angles than the color films of '56, which tended toward a wider view of the action (Memories, the color supplement, has more of an off-the-cuff home movie feel, replete with athletes giggling when caught on camera). Great attention is paid to faces in the crowd, including - as in '56 - Olympic enthusiast Prince Philip, this time barely a month past his wife's coronation on the British throne - where, of course, she still sits almost seventy years later.

Speaking of such anniversaries, I found this historical moment particularly fascinating because the opening ceremony was held on the exact day my mother was born. If one could still detect elements of the present or recent past in the last few summer documentaries I've watched, with Helsinki it feels like we've stepped into a more distant history. This series has entered a period in which the summer documentaries don't really indulge in biography, or any interviews whatsoever. Narrators meticulously guide us through these events and we only leave the field of play for travelogue glimpses of the host city. Nonetheless, some athletes do emerge as stars (and there are cameos from figures who'd become famous later, like a seventeen-year-old Floyd Patterson). And we finally get to witness an already-familiar name in his full glory. For the purposes of this series, Emil Zatopek was introduced offscreen in Rome '60 as a legendary marathoner whose record would be impossible to beat (until an unknown Ethiopian went ahead and beat it) and in Melbourne '56 we got to see him in action, albeit falling way back to sixth due to injuries while underdog Alain Mimoun took center stage. Mimoun is present in the Helsinki film too, but this is Zatopek's year to shine. We watch as he pushes himself hard to win the 5000m and 10,000m (passing people who 'd already passed him near the finish). After these victories, the "Human Locomotive" decided almost on a whim to enter the marathon for the first time and went on to set his famous record and earn a third gold medal. Both Where the World Meets and Memories of the Olympic Summer conclude with Zatopek's triumph, and the main documentary includes an extra treat. Dana Zatopkova, Emil's wife, was not only a fellow Olympian but a fellow '52 gold medalist for the javelin - we see her watch his early track accomplishments from the stands before disrobing and stepping onto the field for her own moment of glory.

Nagano '98 Olympics: Stories of Honor and Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Olympic Glory, dir. Kieth Merrill

Winter 1998 - Nagano, Japan

By now, I've encountered many Summer Olympics that commissioned multiple films but this is only the second Winter Olympics captured from more than one perspective (well, sort of - see my next entry for a complication). Thirty years before Nagano, a couple French documentaries - 13 Days in France and Snows of Grenoble - placed a subtly different spin on the '68 Olympics, often overlapping in events and aspects of style even as 13 Days was more overtly experimental. Memory already blurs them together due to a similar visual aesthetic, featuring beautifully bleary mobile shots of Jean-Claude Killy zipping down the course. This time, however, Bud Greenspan's and Kieth Merrill's works couldn't look more different from one another. Both films feature a glowing, at times purple narration (Stacy Keach guides Olympic Glory while Greenspan, since Lillehammer, has replaced his late brother with Mr. Frontline himself, Will Lyman). But the formal similarities end there. Nagano '98, as we've come to expect from Greenspan, tells its "stories of honor and glory" with a mixed-media approach: film stock, video, archive tapes with timecode and TV graphics, talking head interviews with b-roll captured like a news program after the fact. Merrill's Olympic Glory, meanwhile, is a rarity and a treat - the most visually dazzling winter film since the James Coburn-helmed White Rock in '76, it's unmistakably shot on IMAX. The picture quality has razor-sharp clarity, the lenses are breathtakingly wide, and the vistas are so enormous that even on a home television screen the viewer feels enveloped. Merrill also places screens within screens - creating kaleidoscopic mosaics in order to incorporate more conventionally shot, smaller-frame footage. Together, the two films create a pleasing yin/yang impression of the Olympic spirit at the turn of the millennium, bursting with a particularly American self-assurance indicative of this era.

Greenspan trims his running length to under two hours for the first time (all of his earlier Olympic documentaries exceeded three, sometimes by a lot). The result is a lean, captivating tour through a particularly gripping set of individual portraits, maybe his most uniformly compelling yet. Nagano '98 begins by setting us up for Brian Stemmle's skiing comeback after a horrifying crash that nearly killed him years earlier. But the film brutally pulls the rug out from under this happy ending, when Stemmle misses a slalom gate on a gold-destined final run and watches his last chance at victory, after four disappointing Olympic appearances and the trauma of his past crash, evaporate in the blink of an eye. This leaves the victorious Frenchman whom Greenspan has also been following as a point of emotional contrast, underscoring the "glory and honor" theme that the film's title introduces. While the director's work has always savored disappointment and struggle alongside triumphant celebration, this film feels especially keyed into a melancholy, stoic but romantic sensibility. So many of the competitors that Greenspan centers (even some of the youngest) find themselves at the end rather than the beginning of their career. Although his L.A. and Atlanta films were grander productions placing him comfortably on his own national home turf, Nagano '98 may be the most quintessential expression of his ethos.

The sequence that follows Stemmle's heartbreak traces former world champion figure skater Lu Chen's bronze farewell after a total psychological and physical breakdown. As in the '94 doc, where he mostly eschewed the Harding/Kerrigan melodrama, Greenspan hones in on the gritty struggle of a foreigner rather than the media-hyped rivalry between two Americans - in this case, flashy pintsize teen Tara Lipinski and the more reserved Michelle Kwan. The rest of the film's sequences are: the double whammy of cross-country icon Bjorn Daehlie collecting the most gold medals in winter history (thanks in part to the relay teammate who prevented an earlier win) and then pushing himself to the most exhausting limit to win a race he had absolutely no need to even enter, given his previous record; the poignant final speedskating race of seventeen-year-old Kristin Holum whose mother/coach Dianne was herself a gold medalist in the same sport as well as coach to the record-setting Eric Heiden while pregnant with Kristin (though the film shows the younger Holum dreaming of a future in art, as of her early forties she's known as Sister Catherine - a nun humbly helping the poor in England); the tight competition between the Italian and Canadian two-man bobsled team which, incredibly, results in an unprecedented tie down to the hundredth of a second; Deborah Compagnoni's giant slalom run to become the first alpine athlete to win gold in three different Olympics; and - after a brief mention of the diminutive Japanese speedskating star Hiroyasu Shimizu - a climactic passage on the most suspenseful home team victory of the games, Masahiko Harada's clutch performance for the ski jump team, compensation for famously choking and ruining their final run four years earlier.

Aside from Shimizu, Picabo Street is probably the biggest athlete whom Greenspan mostly skips over. In Olympic Glory, Merill makes up for this by employing her as a partial host, seated on a desert crag to recall her snowy feats. The IMAX doc also takes time to explore a radical advance in speedskating technology (the flexible clapskate) and lingers on the new competitive sport of snowboarding as well as aerials, perfect for the viscerally transporting format. This was a year defined by Gen X in both spirit and dominant demographics, although millennials like Holum, Kwan, and Lipinski were beginning to pop up as supremely talented juveniles. I remember some of the girls in my eighth grade class preferring Kwan and disdaining Lipinski, just a year or two older than us, because they found her giddy demonstrations on the ice a little too bratty. The press definitely emphasized these different demeanors, probably hoping to emulate the much more violent clash of figure skating personalities in '94. I also remember the two skaters on the cover of TV Guide and can recall the marketing of the four cartoon owls who served as mascots (evoking fire, air, earth, and water). In fact, I even seem to remember the appearance of the Nagano IMAX film at the Omni Theater in Boston, which I may have seen at the time. (If so, this would be the only movie viewed before this series, aside from 1936's Olympia.) Olympic Glory carries itself like a nineties blockbuster, produced by Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall, even borrowing music from contemporaneous films including the soaring score of Forrest Gump. This grandiose cinematic style will be delivered in a different manner by the next film we discuss, as will - to my surprise - the winter setting. Because while we're rewinding fifty years for the lush summer games in London, we'll be spending quite a bit of time in the snowy mountains of St. Moritz...

XIVth Olympiad: The Glory of Sport, dir. Castleton Knight

Summer 1948 - London, England (UK)

I snuck a peek at the 1948 film before I'd finished the Nagano duo and was surprised to discover two things. It's in color, despite the bulk of 1952's coverage being black-and-white. And after an opening tribute to the torch relay in Greece (then in the midst of a civil war between communists and nationalists), an entire half hour is devoted to the Winter, not Summer, Olympics. This was fascinating and, honestly, a bit disorienting as I'd grown used to traveling forward for winter events. Yet here I was back in the postwar period, a time of simpler technology and more conservative fashion. How startling for the bobsleds to become rickety-looking open sided sleighs instead of sleek aerodynamic tubes, manned by heavy middle-aged men rather than fit young competitors. How strange for skiers in light winter wear to cautiously navigate the slalom flags rather than zipping at lightning speed through the course in neon spandex. And how unusual for the skaters, speed and figure alike, to glide on outdoor ponds rather than meticulously maintained indoor arenas. I didn't expect juxtapositions this sharp in the series (at least not within seasons) since my progression has been so gradual, but this was a fun way to glimpse how far we've traveled in a half a century. It also makes for an unusual callback since the last time I watched footage from the St. Moritz games, it was in black-and-white and narrated by a Frenchman more invested in his own farcical romance than the events onscreen (remember that one?).

The photography throughout The Glory of Sport is just gorgeous, a delightfully classical approach in vivid Technicolor that makes room for flashes of documentary naturalism - holding on a shot just long enough for us to marvel at the immediacy of these athletes' expressions and exertions, even ensconced in a culture and form far from our own. One memorable moment captures, from a distance but with unmistakable clarity, an argument between two furious cyclists: they've crashed into one another and the angry Turk storms off to sulk by the side of the road. This overall visual panache is particularly welcome since the narration is often quite dry in that formal British way. (This also means that the film avoids the embarrassingly condescending sexism of other postwar documentaries, as well as the bizarre racial tics of the '52 Finnish film, which was incapable of showing black athletes without remarking upon their skin color - at one point even asserting that a white boxer couldn't see his opponent because he blended in with the dark background.)

In terms of its event coverage, the film attempts to be thorough and systematic. After carefully attending to each winter sport in turn before shifting to the bright blue and green of an English summer, Knight focuses his attention entirely on the stadium for about an hour, exhausting the track and field material before traveling off-campus for a variety of other events. He only returns to the stadium in the end for the concluding marathon (won by Argentinian Delfo Cabrera), which once again proves a cinematic highlight. The pounding music and editing rhythms immerse us in the exhausting race but the camera also wisely lingers on the visibly spent Etienne Gailly. Initially in first, he slowly slips back in the last couple minutes, barely able to keep himself from collapsing long enough to win a bronze. The final leg of this epic race - the last stretch on the track when the finish line is right there, in view but not yet reached - has never seemed so excruciatingly drawn-out; the sequence is a bravura stylistic accomplishment.

There's no Zatopek in the marathon this time although we do catch him earlier, experimenting with his inhuman finishing kick to close a gap and nearly win the 10,000m after already winning the 5000 - a double victory he'd have to wait another four years to pull off. I don't recall the narrator mentioning Zatopek's wife but she must be onscreen somewhere, given the attention paid to the women's field events (to be fair, the two Olympians wouldn't marry until later that year so she competed under her maiden name). Fun fact: when Dana eventually medaled alongside her husband in '52, Emil joked that she was inspired by his win and she playfully snapped back, "Really? Okay, go inspire some other girl and see if she throws a javelin fifty meters!" The two would remain together into the twenty-first century, through trying times. Although a prominent Communist in Czechoslovakia, Zatopek's democratic leanings led to punishment following the post-Prague Spring crackdown. He was banished from his wife in the city and eventually demoted to a clerical job, until Vaclav Havel and the Velvet Revolution provided rehabilitation. Zatopek died in his late seventies while his wife joined him just a year and a half ago, at ninety-seven. This film will be the last time time we see either of them as we push further back through the summer games.

Speaking of nonagenarians who passed in the 2020s, London marked the Duke of Edinburgh's first appearance as an Olympic spectator (his father-in-law King George VI opens the games). I also recognized sprinter Shirley Strickland, whom we met at Melbourne for the end of her career, just starting out in '48 (she medaled in three races but was outpaced for gold at every turn by the remarkable Fanny Blankers-Koen). In the winter sequences, we are re-presented with big names from that period like figure skaters Dick Button and Barbara Ann Scott. The film is particularly enchanted with Scott's cheerful smile, initiating a pattern in which athletes grin at the camera and then slowly move toward it, filling the frame. And we glimpse '52 gold medal decathlete Bob Matthias' first victory at just seventeen; when asked how he'd celebrate, the teenager quipped, "I'll start shaving, I guess." That quote is not in the film, of course (nor, unfortunately, is any of Matthias' athletic accomplishments, though we do see him on the winner's stand). We are now very much in the era of silent footage with narration and sound effects added only after the fact. I doubt these film crews carried their own sound equipment in the field.

All of the youthful energy onscreen carries additional weight considering the dozen-year gap between this and the previous Olympics; no wonder The Glory of Sport is eager to encompass winter and summer both. An entire generation of athletes lost the chance to compete at the Olympics between '36 and '48, and in many cases they were unable to appear even when the games finally returned - lost to age if not quite literally lost to the physical ravages of war. The London Olympics of 1948 also makes a striking contrast with the London Olympics of 2012, one depicting an older United Kingdom ready to unfurl its banners of peace after World War II but still retaining some of its proudly straight-arrow wartime posture, while the other captures the pop-inflected, cosmopolitan flash of pre-Brexit Britain. As the critic Peter Cowie observes, The Glory of Sport makes a point of emphasizing Canada, India, and other nascent nationalities as "Dominions" of the British Empire. Jamaica, meanwhile, sent its first team that year, despite its status as a British colony (independence within the dominion would come in the early sixties), and Arthur Wint won the country's first gold medal in the 400m.

Fourteen nations appeared for the first time, many post-colonial, and the Soviets declined their invitation but sent observers to prepare for next time. (This means that, since all films from 1952 to 1992 have been covered, that's a series wrap on the Soviet juggernaut that dominated both summer and winter for so long.) The world - and the Olympics with it - was beginning to change, but the shadow of war still hung over these games. Germany was not allowed to compete but individual Germans did contribute to the London Olympics, since Wembley Way was constructed by POW slave labor (still retained three years after defeat, although the last of these prisoners were likely released just days before the opening ceremony). An initial plan for the captives to work in teams collecting cigarette butts during the actual games was scuttled, as authorities feared it would present too negative an image to the visiting public. Our next trip to the Summer Olympics will land us in Berlin at the height of Hitler's power...but for now? How are the mighty fallen.

Salt Lake City 2002: Bud Greenspan's Stories of Olympic Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Winter 2002 - Salt Lake City, Utah (USA)

Olympic locations are selected far ahead of their scheduled dates: appointed in one era, delivered in another, with no real anticipation of how the host might reflect geopolitical events and trends that aren't even remotely on the horizon. And yet over and over (as we'll very much see in the next entry), these choices coincide with larger forces. The IOC designated the Mormon desert enclave of Salt Lake City as the first twenty-first century winter games host in the summer of '95. At that time the country was reeling from the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil two months earlier: the far right bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City - targeted due to homegrown resentment and fear of the national government. When the Olympics arrived in Utah seven years later, the U.S. was once again reeling from the deadliest terrorist attack on U.S. soil (this time numbering casualties in the thousands rather than hundreds) but the context was entirely different. Instead of militia types, the terrorists were foreign representatives of an insurgent ideology and in response Americans rallied around the flag - and the militant state waving it - as never before. As seen briefly in the unusually hushed introduction to Bud Greenspan's fourth winter documentary (no narration until the last few seconds of this sequence), President George W. Bush anchors the opening ceremony - a glimpse mingled with mythic depictions of torchbearers ascending magnificent frontier vistas. Bush is flanked by the Republican governor of Utah and the state's most famous if not exactly loyal politician, Mitt Romney, who actually organized the games as head of their Olympic committee and then used this PR triumph to launch a gubernatorial run (in...Massachusetts). They are receiving the tattered flag that flew at the World Trade Center from a delegation of New York policemen and firefighters.

A sense of rah-rah patriotism - still, if barely, more exuberantly defiant of enemies than aggressively domineering toward critics - envelops this Olympics and this film. Flags and chants of "U-S-A" are even more ubiquitous than usual, screaming eagles adorn helmets, and competitors wear "NYPD" or "Let's Roll" hats as they warm up or sit for interviews. Salt Lake City 2002 is perfectly situated to convey a zeitgeist that only lasted for a year, maybe just a few months, between the unity following the 9/11 attacks and the clear shift toward a more controversial invasion of Iraq. The flavor of this era, a vague but determined purpose, an elevation tinged in primal fear, anger, and anxiety, still feels palpable to those of us who lived through it, especially those who were young enough to enter adulthood at this time: a sense of the world simultaneously opening up and closing down (I was eighteen when these games unfolded exactly twenty years ago, a senior in high school heading off to New York in the fall). This would be the last time America ever felt so unified, although in retrospect - and for those more clear-eyed at the time - it was unified under an increasingly conservative regime, violently jingoistic in politics and narrowly brittle in cultural affect (hell, on an entirely superficial level, even the haircuts are shorter and tighter than we've seen in Olympic films for decades!). Americans wanted to do something and sought symbolic affirmation everywhere, in random interpersonal acts, in films or shows shot for entirely different purposes, and yes, in athletic achievement. A little over a year later, this need for action - and the ominous dependence upon unworthy leaders to tell us what form this should take - reached its disastrous apotheosis in Baghdad. For now, however, it could find expression in the crowning of an intergenerational gold medal legacy, or even a third place finish for a one-last-chance team leader after years of bitter disappointment.

Greenspan is perfectly suited for this approach, given his propensity to let individual competitors carry much greater narrative weight. The quintessential passage of Salt Lake City 2002 is its first (after the opening ceremony), chronicling the gung-ho Jimmy Shea's victory in the skeleton, a head-first sledding race back in the Olympics after decades of absence. He's following in the footsteps not just of his father, a cross-country skier who competed at Innsbruck in '64, but also his grandfather, a fellow gold medalist who triumphed in speedskating at Lake Placid in '32. That this same ninety-one-year-old grandfather hoped to watch history repeat itself, but was killed by a drunk driver just weeks before the race, only contributes to the pathos of the Shea story, embedding it within a larger quilt of American resilience in the face of tragic loss. Greenspan also locates a similar sense of national struggle and vindication outside of the American camp. His second sequence, perhaps the most dramatically compelling in the film, traces an Olympic trajectory to Salt Lake that goes back even further than the city's selection (albeit not further than the Shea clan's competitive lineage). In 1990, a dozen years in advance, the Yugoslavian handball star Ante Kostelic began planning for his children to make their Olympic debut and carry on the family legacy. Son Ivica was ten, daughter Janica just eight, but sure enough their already-apparent skiing talents would manifest on the Croatian team shortly after Janica's twentieth birthday when she'd win not just one, but a record three gold medals right on schedule. During the intervening decade, their former country was torn apart by war and, lacking both climate and resources, they had to train in the muggy Croatian outdoors and through occasional trips to the Austrian Alps, in which only the little girl was allowed to sleep inside the van (they couldn't afford hotels). If the American sequences - even those tracing Olympic veterans - are fixated on the present tense of national history, the Koselic story casts its gaze back on the global traumas of the nineties, offering hope on the other side.

As for the rest of Greenspan's stories, once again neatly delineated from one another with fades to black and only the occasional side glances at other events: in a rare diversion from rooting for the red, white, and blue, he depicts the Canadian men's hockey team - under the watchful eye of recent NHL retiree Wayne Gretzky - overcoming a half century's humiliating medal drought in a championship match against the U.S. (over a third of Canadians tuned in live to vicariously glory in gold); Stefania Belmondo bookends her ten-year Olympic career with a second gold despite injuries, stolen skis, and a broken pole halfway through a cross-country race; warm weather Australians lose their best chance to finally attain winter gold when aerial champ Jacqui Cooper badly injures herself on a test run, only for teammate and rival Alisa Camplin to win the event in her absence (although Australian gold is achieved unexpectedly before Camplin's performance, when the speedskater Steven Bradbury sails past favorites who'd just crashed into one another and added "doing a Bradbury" to the national lexicon); and finally Greenspan delivers the long-awaited podium appearance of American bobsleigh driver Brian Shimer, considered among the best in the world yet struck with an endless array of bad luck in four previous Olympic appearances. Shimer won bronze despite fierce competition from not only the dominant Germans and Swiss but a fellow American's team - even his rivals couldn't help rooting for him in the end. With America's second- and third-place finishes treated as victories, and Aussie Cooper's bitter disappointment eclipsed by Camplin's charismatic euphoria, Salt Lake City 2002 is perhaps the Greenspan film least absorbed in the poignant valor of a worthy loss or unlucky break. These stories of Olympic glory may be fed by disappointment, grief, or difficult odds, but ultimately they all have happy endings.

Olympia Part One: Festival of the Nations & Part Two: Festival of Beauty, dir. Leni Riefenstahl

Summer 1936 - Berlin, Germany

Olympia opens, as do many Olympic films, in a facsimile of ancient Greece. This time, however, we aren't presented with a brightly-lit, neatly-costumed play of heralds receiving the Olympic torch from a priestess. Instead, in moody, richly-grained black and white, we are immersed in mist and darkness, columns and facades towering overhead, masks and the heads of statues consuming the frame. This is not a tidy, orderly model for civilizations to come but the Greece of the gods, Apollonian perhaps in scale (and brooding tempo) but suggesting the Dionysian in its hypnotic, trancelike quality. The men we see, clad only in loincloth, themselves exhibit a godlike quality, their tactile physicality somehow only reinforcing their impressive stature as they jog in slow motion, cradling a spear or tossing a heavy sphere from palm to palm. When the torchbearer does emerge to race his flame into the fog, we follow a map tracing lines through a dark continent - this is a vision of Europe at least as invested in a notion of primal, pagan power as the European image of Africa. The Olympic stadium in Berlin is presented as a kind of evil overlord's castle, crushing the spectator beneath its blocklike parapets, whose banners are adorned with a harsh occult insignia. Thus opens the first part of Olympia, Festival of the Nations (which will be set entirely within this stadium in order to focus on the warriorlike figures of the track and field stars). In one of the most vivid sequences - apparently reconstructed after the actual competition so that the director could deploy her lights and cameras in more dramatic fashion - pole vaulters arc overhead like slow-motion missiles, spotlit in chiaroscuro, at times almost floating against the black of night. This is one half of Riefenstahl's vision.

The other half is light, endless light, shimmering on the surface of a stream, softly warming the faces of exuberant youths exercising on the Olympic Village lawn, streaming through a narrow window onto the sweaty brows of naked men packed tightly into a sauna, or broken into shivering, cascading crystals by the swooping divers whom the film depicts - celebrating their freedom by taking it further than physical reality would allow - flying out of the water as well as into it, at times suspending them midair by cutting to another slow-motion flip. Again, humans take flight, this time as dark shapes soaring amidst clear skies or a bank of afternoon clouds filtering the sunlight, reversing the elements in the pole vault. So climaxes the second part of Olympia, Festival of Beauty, after opening with that gentle stream, a meditation in nature. Olympia is quite consciously a work of art as well as a sports documentary, and this is especially true of part two. Perhaps due to its influence, many of the footraces and discus tosses inside the stadium feel familiar to someone working their way back to this point. Travelling around, however, Riefenstahl's aesthetic is liberated - or rather, she's better able to impose her own yearning for beautiful order upon this raw material. When, on certain occasions, the footage becomes a bit too rote, Riefenstahl surprises us. An ordinary long-distance shot of rowers gives way to a palpitating perspective inside the boat itself, thrusting us into the megaphone of the coxswain, a delightful visual twist. This constant tension between documentary and contrivance enriches the film, simultaneously allowing a home movie-like glimpse into what it felt like to be a golden youth at this particular moment while also bending human spontaneity into gorgeous formal abstraction. The mesmerizing effect conveyed by the height of these experience is art's for art's sake.

But of course Olympia does not only exist as art, and those images are enlisted in larger purposes. The first purpose is to capture the input and outcome of the various events (especially at a time when live broadcast coverage wasn't really a thing, although viewing rooms stationed around Berlin did allow these to be the first televised games in a limited fashion). This purpose is particularly acute in part one but present throughout; at times, this practical demand brings the movie crashing back down to earth in a fashion one might appreciate as an Olympic historian but resent from a cinematic perspective. For all of its exceptional style, it is striking how Olympia fits within the larger genre which, again, it helped to create. Even the split structure, track and field in one half vs. outside events in the second, would be echoed later on, and of course in comparison to something like Visions of Eight or Marathon, significant stretches of Olympia feel almost conventional. As with most of the films from '68 or earlier, there's also no attempt to sculpt any narrative or biographical aside. Event follows event follows event - that tends to be the structure these early films rely upon; after all, in the pre-saturation era of Olympic broadcasting, documentary features had to pull double duty as reportage as well as creative exploration. Perhaps some of the innovations in Festival of Nations will come into sharper focus when I watch the handful of remaining silent films and glimpse how close they do or don't get to the action. Something else that hit me due to my method of viewing backwards: none of the athletes are familiar given the long pause between Berlin '36 and Helsinki '48. A continuity has been broken with one big exception, a participant we meet in later films as a spectator...but we'll discuss Jesse Owens momentarily.

Other notable athletes onscreen include Koreans Sohn Kee-chung and Nam Sung-yong winning gold and bronze for Japan, the nation that had swallowed up their own. German victories with the javelin, hammer, and shot put were kept from a clean throwing sweep by American Ken Carpenter's discus throw. Owens' rival Luz Long offered (offscreen) advice to help Owen win, both of them setting records with each long jump and establishing an enduring friendship despite fighting on opposite sides of the coming conflict (Owens would eventually deliver Long's personal correspondence to his orphaned son after the war). Silvano Abba is the Italian victor in the riding portion of the pentathlon, eventually winning the bronze when all five events were completed. This was a precursor to his death at Stalingrad in the last cavalry charge of millennia-old military history. And the American team won the first-ever women's 4 x 100 relay when the almost guaranteed-for-gold Germans drop their baton. Of particular note on that U.S. team is its third leg, Betty Robinson, whose backstory remains untold in the film (Bud Greenspan would never have let this one slip through the cracks). Victim of a 1931 plane crash, she was presumed dead when found in the wreckage, packed into a trunk, and delivered to a morgue before anyone realized she was actually in a coma. There have been some extraordinary comebacks for gold (marathoner Alain Mimoun's near-amputation comes to mind), but I think this might be the one to beat. Finally worth mentioning is Glenn Morris, whose prowess so impressed the Germans that they invited him to stay behind and make a series of sports films. He chose Hollywood instead and became one of four Olympians to play Tarzan. In 1936, this extraordinary decathlete broke a world record and also, it appears, the filmmaker's heart. Riefenstahl later reported a torrid love affair with Morris in her memoir, although at least one detail of the story appears to be made up. She claims he kissed her breasts in front of the entire crowd upon receiving his medal, but the historical record shows an ordinary ceremony in which the gold was presented by another famous figure's lover: Eva Braun.

As for the film's other purpose, beyond documenting a world sporting event? Well, you know where this is going.

Shortly before writing my review of the Salt Lake City film, I began watching the 2022 Winter Olympics - tuning in live to the broadcast and also accessing earlier events on demand. This was the evening before the parade of nations and lighting of the torch, so I hadn't expecting anything to be on TV but apparently certain events are scheduled ahead of the actual games (curling and the figure skating short program, as well as qualifying heats for ski moguls). Due to this unexpected timing, by the following evening I found myself alternating between the final passages of Riefenstahl's Olympia and NBC's prime time presentation of the opening ceremony in Beijing. I'll be discussing the latter in more detail eventually, as the final entry in this series, but for the sake of this piece it's the political context that holds the most salience. With comparisons to the '36 event already in the air, the network awkwardly attempted to provide its usual glowing coverage of athletes and spectacle while simultaneously addressing a myriad of human rights and national security issues (not just with China but also Russia, given the current massing of troops of the Ukrainian border). The mix was heavy-handed, at times even darkly comedic, but one imagines - charitably, perhaps - that the programmers were haunted by the ghost of Leni Riefenstahl and wanted to avoid being implicated in the glorification of a human rights abuser. Certainly switching between these two modes of viewing the Olympics was a surreal experience for me, highlighting the limitations of both approaches which exist at almost opposite extremes. In comparison to Riefenstahl's gorgeous and disturbing mythic reverie, the executives of NBC (and their U.S. State Department handlers?) came off as almost Brechtian, subverting themselves as well as the Chinese Olympic Committee - a gap not only of purpose but of finesse.

Of course, Olympia holds its own seeds of self-subversion. Riefenstahl, like D.W. Griffith birthing blockbuster entertainment with his Ku Klux Klan-celebrating The Birth of a Nation, is all too good at her job but, also like Griffith, history has made it impossible to view her work as originally intended. I once wrote of Birth: "It's as if Griffith was secretly hearkening to avant-garde political filmmakers of fifty years later, the types who would like to link up manipulative filmmaking techniques with political repression and reaction. With the hindsight of 90 years in a post-civil rights era, the movie seems to be using the Reconstruction era to deconstruct itself." Likewise, in Olympia the dazzling, often immersive photography of athletes is sprinkled throughout with swastikas, Nazi salutes, and glowing close-ups of grinning officials who would be hanged for war crimes in less than a decade. Any moment we may begin to fall entirely under the film's spell is rudely interrupted by a reminder of where all of this is headed. A swimmer celebrates her victory, the sun glinting off her flaxen hair, and we could be experiencing a heightened vision of mid-thirties Hollywood glamor on a golden afternoon - oops, there's a smash cut to a grinning Adolf Hitler descending through the crowded stands to join the fray. This reminds me of the avant-garde montage used to train assassins in the 1971 thriller The Parallax View, in which warm images of home and family are intermingled with jarring images of pain and violence (including of Hitler himself, by that time synonymous with evil). Except that Riefenstahl, of course, wasn't trying to pull us out of the swim meet by reminding us of Hitler, she was trying to build enthusiasm for him in an audience already softened by the athletes' and spectators' joy, by the music, cutting, and play of light across the swimming pool ripples. This effect only backfires because of our later knowledge of World War II and the Holocaust.

The film also brings to mind another quote from an early piece of mine, in this case covering Riefenstahl's own Triumph of the Will (with significant asides on the Nazism-as-aesthetic documentary The Architecture of Doom and Susan Sontag's essential essay "Fascinating Fascism"):

"What I was reminded of was the stereotypical American reaction of the time: as Hitler ranted and raved on and on about his glorious Fatherland, I pictured a wisecracking Yankee newsman chewing loudly as he rolls his eyes and jots down every crazed word of the Teutonic loon. This dismissive response, perhaps a form of self-protection as much as anything else (those nutty Germans, they aren't like us commonsensical, democratic folks) has been obscured by the very real damage Hitler unleashed, but watching the film as an American, and one well-acquainted with films like The Great Dictator, To Be or Not to Be, and numerous anti-Hitler Bugs Bunny cartoons, this attitude was reawakened in my mind."

Naturally, the crushing monumentalism of Olympia does not find room for a sarcastic takedown of the Fuhrer (the closest it comes to comedically undermining militaristic impressions is during an extended eventing montage of fully-uniformed officers crashing their steeds in a river). That said, the film does allow for a subtle American undercutting of another sort, in the form of Jesse Owens' legendary four gold medals. Riefenstahl focuses extensively on what may be the greatest athletic feat of the games, one that spurred some resentment among Nazi officials. Before the 800m is won by another African-American - John Woodruff rather than Owens - we even hear an offscreen announcer intone, "Two Negroes competing against the strongest of the white race." But Owens, captured in close-up repose and preparation as well as full-body depictions of his strides and leaps, is generally treated with admiration...if not (for better or worse) the objectifying, fetishizing gaze that Riefenstahl lavishes on Aryan archetypes, who parade before her camera in staged displays of fitness and dexterity in both halves of the film. Long revered as a symbol of American pluck and talent in the face of foreign fascism, Owens' status is of course complicated by the way he was treated back home by the Jim Crow status quo. As he once resentfully observed, it was ultimately Roosevelt, not Hitler, who snubbed him: "The president didn't even send me a telegram."

Meanwhile, Marty Glickman, a Jewish runner on the U.S. team, felt that he and teammate Sam Stoller were dropped from the relay line-up at the last minute for fear of embarrassing Hitler inside his own stadium. Certainly American Olympic officials were worthy of suspicion. Avery Brundage, the head of the delegation at the time, later the head of the entire IOC, decried a "Jewish-Communist conspiracy" against American participation in the games. When he went on a Nazi-guided fact-finding mission in 1934 to determine whether Jews were being discriminated against, he ended up pleasantly commiserating with his guide about how he too attended athletic clubs with exclusionary provisions. The German government temporarily lifted many racist restrictions in the city leading up to the Olympics, although they further "cleaned up" Berlin by imprisoning Romani people in concentration camps. They also permitted Jewish participation, even re-importing a Jewish fencer (Helene Mayer) who'd fled to America following Hitler's rise, placing her on the German team. When she won a silver medal she offered a stiff-armed salute from the podium. Mayer later said she hoped this gesture would help her relatives still trapped in Germany, although she became a controversial figure upon her return to the U.S. According to the Holocaust Museum, eight other Jews medaled in Berlin - half of them Hungarian. Most lived to a healthy old age, although another fencer, the double gold-winning Endre Kabos, would be killed when the Germans destroyed a bridge he was crossing to deliver food between two Jewish camps. Over four hundred Olympians would lose their lives in World War II and while I haven't done a close check, it would stand to reason that the majority of those casualties competed in Berlin. Who knows how many in the cheering, saluting crowds would also be dead within a decade, once this glittering city was reduced to rubble?

In addition to its poisonous political undercurrents, Olympia exists in a strange space inhabited by many interwar works, even those created during the grueling devastation of a worldwide depression. We're often trained to read history as progressive evolution - a trajectory that the rapidly-shifting technology of cinema only reinforces: from silence to sound, black-and-white to color, academy ratio to widescreen, celluloid to digital, and so forth. Even on a backwards journey, as with our survey of these summer documentaries, the steps along the way feel orderly. But twenties and thirties cinema presents us with a picture of affluent, middle-class, even at times working-class modernity and comfort that would be utterly decimated by World War II, yanking Art Deco glitter into the Dark Ages. Given enough time, every face in every film will become haunted by its own future, but few faces are as haunted as those captured just before the worst war in history. Olympia closes, as do many Olympic films, when the flame in the grand cauldron is extinguished. The effect is bone-chilling. Though utterly unintended, the symbolism of this moment feels less ambiguous than anything else in the film, its trail of smoke evoking a metaphorical dream snuffed out, a literal city burnt to ashes, or simply the awful pyre of a crematorium. The black hole to come will swallow up everything, including the Olympics and including many of these Olympians. Because I'm watching this after the subsequent films rather than before, I retained a subtle, haunting impression of uncanny recurrence. I'd already viewed the documentaries which ponder the legacy of the war, proclaiming values of peace and tolerance and brotherhood. And yet here we are, slipping with such incredible ease into the familiar sights and sounds of the eternal Olympiad - embedded in an environment we now instinctively recognize as the epitome of evil, inside a world hurtling toward an apocalypse. Many back then recognized this too. Many did not. We want to shout a warning at the screen, but perhaps the warning is for us.

+ bonus Summer 1932 in Los Angeles, California (USA)

As noted while briefly covering the '32 winter games in Lake Placid, YouTube has many more newsreels (and home movies) available for the Summer Olympics of that year. I didn't watch all of them. But after viewing three or four, totaling over an hour of footage, I got a pretty good survey of the events ranging from rowing against the industrial backdrop of Long Beach to swimming and diving in the same outdoor pool, to, of course and especially, the track and field events at the familiar Memorial Coliseum. That location feels quite familiar from the '84 film and the stadium will be employed for a record third time in ninety-six years, when L.A. becomes the third city to host three Olympics (the others are London in 1908, 1948, and 2012, and Paris in 1900, 1924, and 2024). This makes the Coliseum among the most consistent icons of the modern Olympics, since cities usually build new facilities every time they host. The online clips tend to be photographed from a distance, especially when it comes to races, so there's plenty of room to take in the sweep of this structure. That said, one program does feature the victors smiling in close-up after presenting each of their accomplishments.

Although America hosted two Olympics in '32, President Herbert Hoover declined to open either of them. In this case his Vice President, Charles Curtis, assumes the duties, probably better optics for Hoover than during the winter, when the man who'd end up challenging and beating Hoover for the presidency opened Lake Placid (after all, Roosevelt was then governor of New York). As expected from newsreels, the emphasis is on the moment of competition with the results on a title card (most of these videos did not have any accompanying sound except an occasional moody, ambient modern score, reinforcing the sense of distanced nostalgia). One particularly notable moment: Eddie Tolan is granted the gold in a 100m photo finish despite recording the exact same time as Ralph Metcalfe, who would always claim it should have been a tie (the stopwatch back then measured in tenths rather than hundredths of a second). Perhaps the most evocative footage from these games captures inviting bungalows under the warm California sun, as a Chinese athlete warms up in the Olympic Village. It helps, of course, that I'm currently writing this while looking out the window at an icy New England winter.

Bud Greenspan's Torino 2006: Stories of Olympic Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Winter 2006 - Turin, Italy

From the most notorious Olympic film, and Olympics, we now turn toward one of the more obscure - both the film and the event itself. At least that's how it feels to me; setting off on this journey, I had trouble even remembering where the 2006 winter games were held despite being twenty-two at the time, probably more in line with the athletes' ages than I would be before or after. (Or so I thought; looking it up, the average age is actually twenty-seven...see you in Vancouver.) Despite distinct memories of watching something in my Brooklyn apartment - I think maybe the first-ever team pursuit speedskating (with groups of opponents going in opposite directions around the rink) - this is probably the Olympics I paid the least attention to. I was preparing a big project and had other things on my mind; looking back now, the there-but-missed-it quality only adds another layer of poignancy to the nostalgia. Many of the YouTube comments on the Olympic Channel's upload reinforce this: "I'm from the US, but there was something about this winter Olympics. Turin made the world feel that we all came from the same village, city, country. Still my favorite Winter Olympics :)" And so forth. To indulge a digression, I'm also reminded of the way I began my recent Journey Through Twin Peaks return video, by superimposing the title "2006" over David Lynch's digital short Ballerina, from about this same time. Its blurred presentation of a dancer in a red dress, enveloped in gray fog, evokes the athleticism and even the digital aesthetic of this other mid-zeroes artifact (there's that Lynch/Bud Greenspan connection for your bingo card). That year ends up feeling, to me, like a subtle but important bridge between past and the present for personal as well as broader cultural reasons.

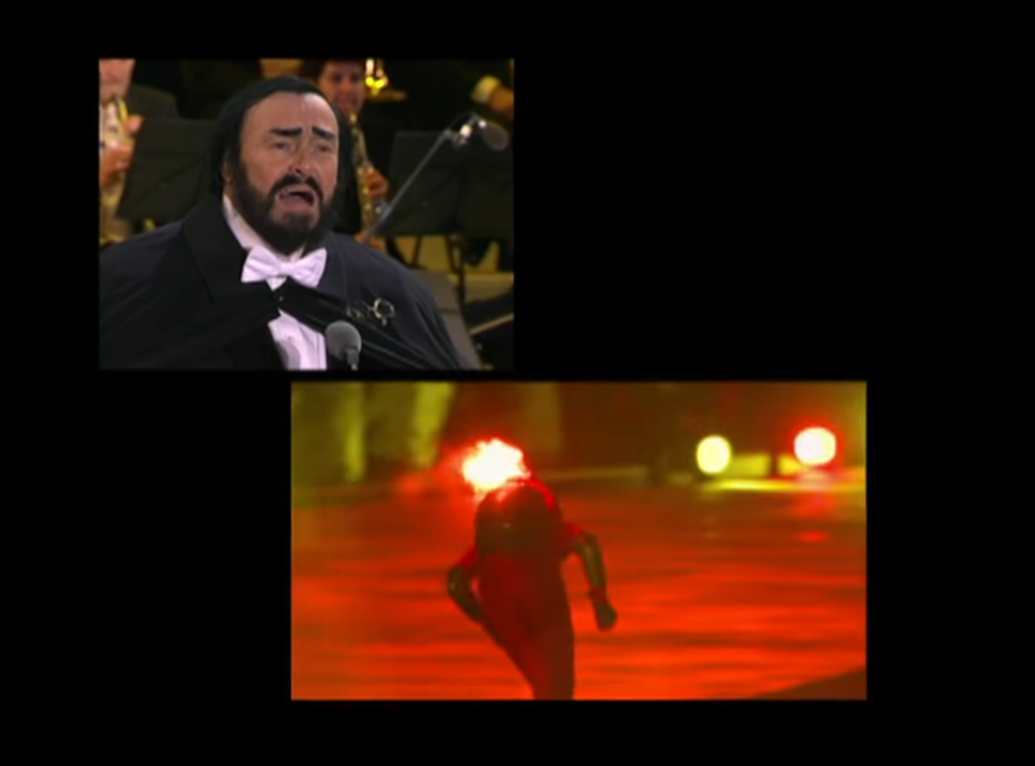

Greenspan, a long way from the spartan spirit of Salt Lake City, allows a flamboyant Italian mood to infuse his depiction of the opening ceremony (the film notes in its closing narration that Turin is actually perceived as one of the most reserved cities in the country, but threw this reputation aside to embrace the motto "Passion lives here"). Luciano Pavarotti sings - or rather, lip-syncs due to the extreme cold - Nessun Dorma in his last public performance before dying a year and a half later, and Greenspan uses checkered screens to juxtapose this aria with other elements from the gaudy, operatic opening ceremony. This is a crescendo for the director too, sealing off a dozen-year uninterrupted run as the auteur of Olympic cinema - even the '98 IMAX film was produced alongside, rather than instead of, his effort. Turin was the seventh Olympics he covered in a row, the ninth overall (his fifth winter). However, Torino 2006 is also one of Greenspan's shortest documentaries (less than an hour and a half) and the one that most feels made-for-TV although many of his later works were also produced for Showtime. He, like Pavarotti, may have been getting tired with age - the next summer film would be the first that he didn't direct, and the subsequent winter entry would be his last, requiring a collaborator to finish the work after he died. The stories are also a bit lighter than usual in terms of dramatic stakes and personal depth, and there's a sense that Greenspan is becoming a figure of Olympic past more than its present.

This is most evident in the surprising exclusion of what may have been, for Americans, the breakout story and star of these games: the emergence of snowboarding as a frontline event in the American media thanks to a team headlined by Shaun White, who'd go on to win so many medals in his long career that Wikipedia requires a separate drop-down menu to count them all. The nineteen-year-old's distinctive orange locks are nowhere to be found onscreen in Torino 2006, as Greenspan prefers to trace more grizzled veterans pursuing one last chance at glory. Perhaps if he was still around, the director would be more interested in documenting White today, since the athlete is right now pursuing a fourth gold medal in his fifth and final Olympics. (By the time you read this, you'll know if he succeeded.) Instead, Greenspan focuses on the following subjects: nineties rollerblader turned zeroes speedskater Joey Cheek, who dedicates his gold medal bonus to charity and devotes himself to helping the victims of ethnic cleansing in Darfur; the overlooked Japanese figure skater Shizuka Arakawa, ascending to the top of the podium as her favored competitors stumble; Enrico Fabris, honoring the host country with his completely unexpected speedskating bronze followed by two golds, thanks to his exceptionally strong final laps in every race; Norwegian legend Kjetil Andre Aamodt cementing his five-Olympics run with a fourth gold (third in the Super-G and eighth medal overall); and Giorgio Di Centa, brother of cross-country star Manuela who featured in Greenspan's '94 documentary, carrying on the family legacy by delivering the Italian team two more gold medals in the event. For the first time, every Greenspan subject is a medalist; hell, for the first time, every Greenspan subject is a gold medalist. The filmmaker, so often enamored of noble failure, spends his last full production glorying in unvarnished success.

The current Olympics will end in four days. I'll be back next Wednesday to conclude with the earliest available summer documentaries (Amsterdam 1928, Paris 1920, and Stockholm 1912, mixed with newsreels or even photo-based coverage of Antwerp 1920, London 1908, Athens 1906, St. Louis 1904, Paris 1900, and Athens 1896) and winter documentaries leading right up to my response to the latest broadcast (Vancouver 2010, Sochi 2014, PyeongChang 2018, and finally Beijing 2022).

No comments:

Post a Comment