for the introduction & line-up of monthly capsules

running from August 2021 to February 2022

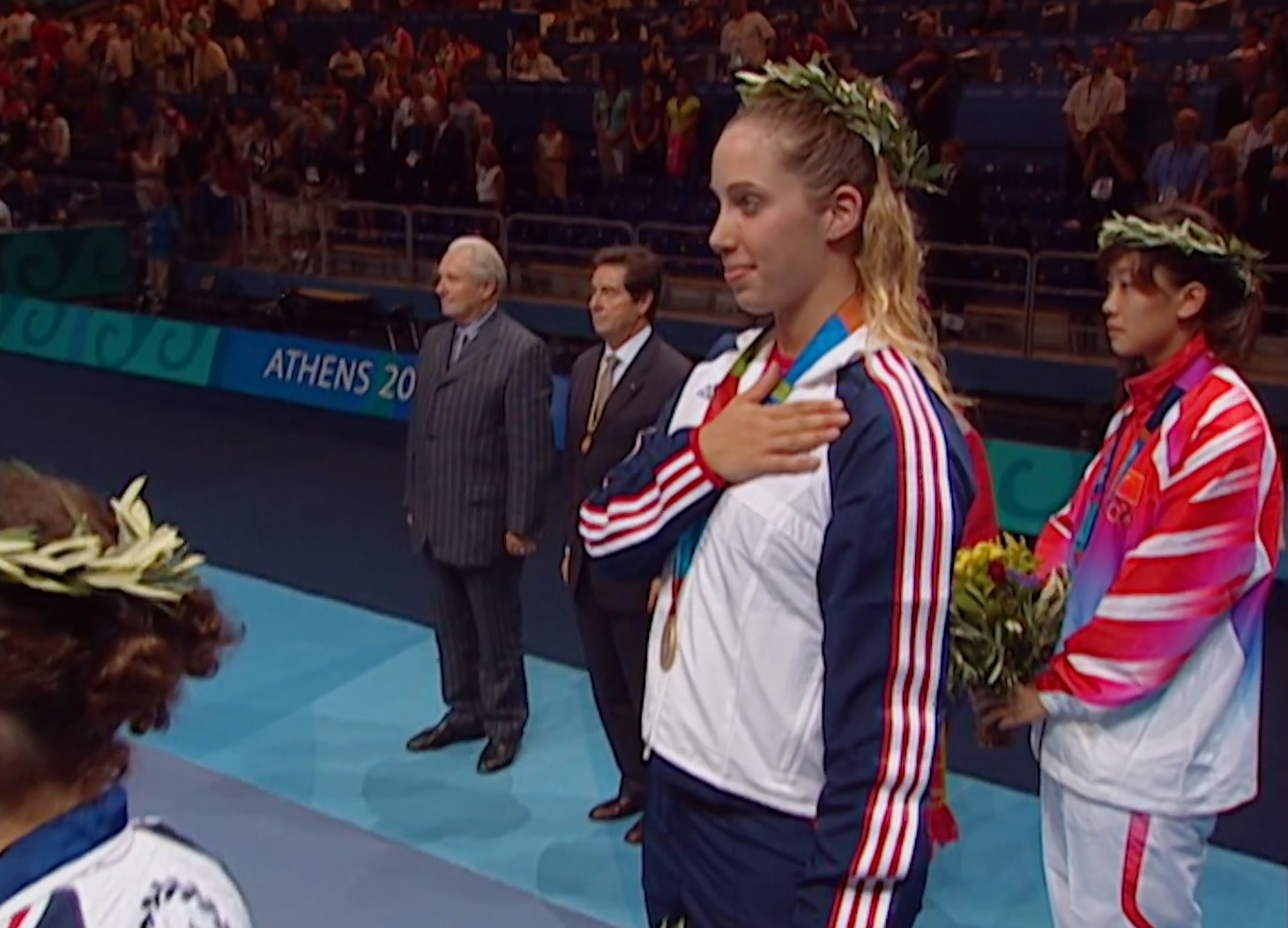

Bud Greenspan's Athens 2004: Stories of Olympic Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Summer 2004 - Athens, Greece

Although its placement is random (these groupings are broken into roughly equal size rather than thematic cohesion) this film provides an appropriate entry point for my much-belated second round of Olympic coverage. The location is Athens, primal scene of both the ancient and modern games - as Greeks were more than eager to remind everyone seventeen years ago. That's a key number, roughly the size of a generation. On my own backwards-looking voyage through summer events, it now truly feels like we are entering a distinct period of history removed from our own. I've already noted how even recent events already indicate the passage of time (especially on the other side of a pandemic) but by this point, most of the athletes we'd recognize from the 2010s Olympics - including those who were already retired by 2021 - have yet to arrive on the scene. Usain Bolt, star of the other three summer Olympic films we've discussed, is probably the most notable absence. There's also the fact that this documentary itself is by design very backward-looking. Each segment, focused on a particular athlete's 2004 struggles, makes ample room for footage from earlier Olympics and other competitions, framing their victories (or final disappointments) as culminations. Past and present are interwoven as we learn the long histories of a Greek weightlifter carrying the entire host nation's hopes on his tired shoulders, a Moroccan marathon runner whose dozens of international victories are overshadowed by his losses at every Olympics, and a deeply religious Polish swimmer who dedicates (and auctions) her medal to the benefit of children with leukemia.

We linger especially long over the journey of American softball pitcher Lisa Fernandez, whose team seeks and achieves gold for the third time in a row - for what would turn out to be the last time. Eighties home movies show her as a child playing in her backyard, and then we follow the '96 and '00 match-ups blow by blow. Now pushing into her mid-thirties, Fernandez rallies the team again - all as their coach grieves the recent death of his wife. By the time of Beijing four years later, the aging Fernandez would be cut from the team, relegated to the role of alternate, so this is her swan song. It's valedictory for filmmaker Bud Greenspan as well. Given the unusual structure of these round-ups, this is our first encounter with him, but he directed nine Olympics documentaries, far and away more than anyone else (the handful of runners-up have just two to their name, usually back to back). Athens was his third summer doc in a row and also the twentieth anniversary of his first effort. Although he'd continue to direct the winter films until his death in 2010, the IOC selected a Chinese filmmaker for the next summer event (as we've already covered). Therefore this series' introduction to Bud is, in a way, through a farewell. Less flashy than his successors (or many of the winter predecessors I've already discussed), Greenspan's preferred approach - at least based on this small sample size - is more focused on storytelling through individual portraits than in aesthetic exploration or painting a larger social portrait. There's a crowd-pleasing touch here; I've watched many of these selections with my parents, and both proclaimed this their favorite. This is also chronologically the last summer film that Criterion presents in a classic, televisual 4:3 frame, further burnishing its old-fashioned credentials.

Fight Without Hate, dir. Andre Michel

Winter 1948 - St. Moritz, Switzerland

This documentary quite clearly expresses its theme through title as well as opening montage, using still photos of past games - going back over half a century - interrupted by two world wars. The otherwise droll narration, initially teasing the fashions of long-ago athletes, strikes a more somber note over images of empty stadiums in '40 and '44. Ultimately, however, the postwar flavor of the second St. Moritz Olympics in twenty years is conveyed more through irreverence than sobriety. Our narrator keeps up an insistent banter with his flaky wife as sidekick - indeed, this movie has a "plot" which takes place entirely on the soundtrack and has little to do with what we're watching. Over images of skiers flying down the slopes or hockey goalies sliding for a save, the jaunty Frenchman tells us (repeatedly) that women are vain and foolish creatures, while debating whether or not to buy his spouse a silk black jersey that she envies on one of the athletes. There's even a third interlocutor, a bumbling foreign policy commentator who makes inane contributions before suspiciously disappearing with the main announcer's wife. Again, these bits are conveyed in cutaways - they are essentially part of a radio play unfolding simultaneously with the collected footage of various events. It makes for a bizarre if amusing experience which I suspect won't be repeated. This is one way to deal with the expectation of sound in late forties cinema, especially since actually recording audio during these conditions would have posed a technical challenge.

The cinematography remains black and white, perfectly suited to the crisp white landscapes we've visited once before. Particularly striking sequences include subtly kaleidoscopic superimpositions of twirling figure skaters, as well as a camera attached to the front of a bobsled (still dubbed "bobsleigh" in the subtitles), creating a sensation like an amusement park ride as we race down the course at thrilling speed. The male downhill competitors face a particular challenge staying on their feet, and both editors and writers have fun with the Italians taking constant spills; during the opening ceremony, it's noted that they wear "white caps" and their desperate but often disappointed thirst for victory is a consistent theme. Perhaps this is coincidence, though it's notable that Italy was the only Axis power invited to the competition, so they get off lightly with mere mockery. Not only are Germany and Japan absent, I didn't catch any Soviets either (a little research shows, to my surprise, that they didn't compete in any Olympics until the following cycle - I thought I'd spotted them in one or two of the earlier documentaries, but apparently not). With both Cold War and recent World War II enemies absent, it's no wonder that a fight without hate can unfold. By the way, our offscreen protagonist does indeed win his wife back, albeit at the expense of several jerseys instead of just one.

Sydney 2000: Stories of Olympic Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Summer 2000 - Sydney, Australia

Now back to the turn of the millennium. At the end of Fight Without Hate, the narrator wondered if someday future audiences would regard the then-ultra-modern 1940s fashions and sensibilities as relics of the past. This already feels like the case for the once-unimaginably futuristic year 2000. As with Greenspan's 2004 documentary, Sydney 2000 is wrapped in a very nineties aesthetic with its narrow aspect ratio, brightly-lit talking head interviews, and fuzzy video quality. The hairstyles, clothing, and even the general attitude also seem to belong more to the previous decade than the forthcoming one. Prior to 9/11, Iraq, and the financial crisis - for perhaps the last time on such a widespread basis - an air of confident, almost swaggering optimism pervades the dawn of a new century. This feels especially true for the U.S., captured in the cheerful American baseball victory over Cuba a few months after the tensions of the Elian Gonzalez controversy (which the film does not mention) and for host country Australia, jubilantly cheering many of its athletes but particularly Cathy Freeman. The Aboriginal runner became the embodiment of the nation's hopes to surpass its history of racist conquest with a common, diverse sense of patriotism; Freeman lit the Olympic torch at the opening ceremony, won the 400m footrace to a delirious outburst of cheers, and then ran her victory lap carrying the flag of both her country and her people. This crescendo arrives an hour and a half after the film opens with an assembly of rare if obvious flourishes for a mostly meat-and-potatoes production, with Dorothea Mackeller's poem "My Country" read over lush footage of kangaroos and koalas, dazzling shorebreaks and the gleaming red of the tellingly double-named Uluru/Ayers Rock. All countries wish to glorify themselves by hosting the Olympics but few have been more successful than Australia in 2000.

That night of track and field forms the climax of the movie, not only due to Freeman's triumph, but for Michael Johnson's last Olympic appearance (netting another gold medal), Haile Gebreselassie's breathtaking 0.09-second victory in the 10K, and a number of other events like the pole vault and discus throw simultaneously taking place inside the ring of runners. Regarded as one of the most historic nights in sports, this - as well as that general air of optimism - contribute to the IOC president's closing remarks that this has been the greatest Olympiad of all time. Of course, these summer games barely unfolded in the summer at all...since Australia celebrates its summer during the northern hemisphere's winter, the Olympic schedule compromised with a September-October run. While I don't recall much about the 2004 Olympics, I do remember these 2000 events taking place on school nights during my junior year of high school, in contrast to the usual summer vacation backdrop. I also remember the time difference providing a frustrating impediment to live viewing, especially since the previous Summer Olympics had unfolded in the same time zone. Something else I was struck by on this viewing: the athletes were still all older than I was (now, I'm usually older than them). This was the zenith of Generation X's Olympic dominance with almost everyone we're watching born in the sixties and especially seventies. A rare millennial exception is Australian swimming superstar Ian Thorpe, just shy of seventeen, who bests a highly competitive American for Sydney's first shot at hometown pride. Another exception, never shown onscreen but present at the games as a fifteen-year-old, was Michael Phelps. Indeed, Greenspan skips a lot of big athletes in his more focused coverage with perhaps the most notable being Marion Jones, a breakout American star but later as disgraced as any Olympic veteran when all of her medals were stripped due to doping. She appears for just a few seconds in the closing montage.

One of the film's biggest names is much older: foulmouthed Dodgers legend Tommy Lasorda turned seventy-three while guiding his motley crew of amateurs to their aforementioned victory. Sydney 2000 lavishes great attention on his age-defying energy and no wonder, given the fact that Greenspan celebrated his own seventy-fourth birthday a few days before Lasorda. Greenspan does not receive writing credit (that goes to Bruce Beffa) and his role may have been less hands-on traditional director and more "executive" as IMDb lists him, side by side with two co-directors whom Criterion doesn't mention (Andrew Squicciarini and Sydney Thayer). However, the film's structure and style are obviously linked to the later Greenspan doc I just discussed. In this case he doesn't fold in past Olympics as thoroughly Athens 2004 did, but both films spend long stretches honing in on a few competitors - allowing their individual stories to provide the muscle on the larger event's bone. There are five distinct focus points in Sydney 2000 before the aforementioned track and field "night of nights": swimming, equestrian, baseball, cycling, and the decathlon. The central figures tend to be the victors, with some attention given to close runners-ups - this film is less interested in digging into disappointment than the later documentaries I've watched, in keeping with its jubilant tone. That isn't to say it ignores the darker side of competition even while emphasizing the silver lining: the chronological and emotional centerpiece of the narrative is carried by thirty-year-old Dutch cyclist Leontien van Moorsel, an early nineties superstar who descended into a horrific and presumably career-ending battle with anorexia. Greenspan captures her triumphant return under a new name - Leontien Zijlaard - which she briefly adopted in gratitude to the husband and trainer who helped her dig (or pedal) her way out of despair.

The VI Olympic Winter Games, Oslo 1952, dir. Tancred Ibsen

Winter 1952 - Oslo, Norway

Surprisingly, it took twenty-six years for the the Winter Olympics to reach Scandinavia. The Swedes, Norwegians, and Finns make the most of their traditions, crowding out the other competitors in many skiing events. Ibsen (yes, he's from that Ibsen family) opens the film with a tribute to centuries of sport in the region, shooting the descendent of a famed skiing legend lighting the torch in the fireplace of a mountain hut and then sending it on its way down the glistening slopes. From this primitive origin, however, Oslo 1952 shifts to a more modern locale. For the first time, the games unfold in a bustling metropolis rather than a quaint resort town (although the Lake Placid newsreels reveal a more crowded event than prior or subsequent films). Hockey in particular appears to have taken a great leap forward - no longer a slapdash affair on a frozen pond, it's now conducted professionally in a boisterous arena with a large scoreboard and penalty box to keep the frequent fights in check. Crowds are enormous, especially for the final ski jumping competition, with 140,000 people sprawling into the distance around and beyond the landing area.

The camera goes a bit further than it has in the past, capturing hockey pucks in motion and even helmeted drivers in the foreground of its inside-the-bobsleigh run to let us know we're right there with the athletes themselves, an effect that the selective use of (usually post-dubbed) sound effects also contribute to. There is, notably, no jocular narration this time, just a highly serious and technically detailed commentary on what we're seeing - albeit still one to indulge in the occasional aside about a pretty young athlete. While Fight Without Hate was particularly keen on the media's activity, following reporters as they phoned in their observations and photographers wiring their snapshots across the Atlantic, Oslo 1952 is more interested in the athletes themselves, tracing their leisure moments including a Spanish faction (are these tourists? I don't recall any Spaniards in the competition) who stage a mock bullfight in the middle of a restaurant. Incidentally, if the measured beauty of the composition and lighting/exposure feels reminiscent of Ingmar Bergman's precise, evocative Swedish cinema, that may not be a coincidence - at least some of the footage was taken by Gunnar Fischer, Bergman's cinematographer in the late fifties.

Atlanta's Olympic Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Summer 1996 - Atlanta, Georgia (USA)

Due perhaps to the centenary - the first modern Olympics were held in Greece in 1896 - or maybe because the games are back on American soil after a dozen years, Bud Greenspan depicts the Atlanta event in an epic three and a half hours. Presumably the documentary was split into installments for TV viewing, though notably the photography has a more cinematic feel than some of his follow-ups with its grainy celluloid texture (the frame is even letterboxed for the grand opening). Greenspan has obviously dominated the summer coverage with his trilogy in this round-up (plus the L.A. games in '84, his Olympic debut) but overall he was more of a presence in the winter department, with a total of seven documentaries there. Like his other films, Atlanta's Olympic Glory concentrates on single athletes and deep-dives on particular sports rather than attempting to cover a broad swathe of the competition. This includes several areas we haven't spent much time on elsewhere, including archery (in which archetypal X teen Justin Huish sends his father's very nineties camcorder reeling in joy after his victory) and crew (in which the unusually working-class British rowing star Steve Redgrave anchors both his vessel and Greenspan's narrative - as well as the entire UK Olympic team, collecting its only medal). Greenspan also spends plenty of time on the usual suspects like swimming, cycling, and track and field. As always, runners provide the most crowded field with the film making room for various marathon, sprinters, and short-and-long distance stars. This includes - among others - Wheaties cover man Michael Johnson's record-setting performance; the legendary Carl Lewis' fourth and final gold in the long jump; the injured, retiring Jackie Joyner-Kersee's touching, hard-fought battle for a bronze; and Inger Miller's family-fueled fourth place photo finish, one of the few times Greenspan dwells on someone who doesn't place in their main event (although she does go on to collect a gold with the relay team).

The personal approach hits its peak with a trio of portraits. Jeannie Longo, a French "monstre sacre" cyclist whose international status has failed to materialize in a win amidst injuries, misunderstandings, and other frustrations, finally gets her gold. Chinese-born gymnast Donghua Li also emerges a champion after leaving his country and awaiting Swiss citizenship for five years (foregoing a likely star performance in '92 in the process), all to be with the love of his life, whom he met and fell for over ten days in Beijing. And Josia Thugwine, a black South African coal miner who dedicates his very close marathon victory to Nelson Mandela, only recently inaugurated as the president of a united post-apartheid nation. We're reminded here as elsewhere of how the new the world of '96 was. This is also true of post-Cold War, re-located athletes like both the featherweight lifting silver and gold medal winners, Valerios Leonidas and Naim Suleymanoglu who, respectively, left behind the USSR and Bulgaria to return to ancestral homelands (and nationalistic rivals) Greece and Turkey. (Suleymanoglu in particular has an extraordinary story, sneaking away from his Bulgarian team during a time of ethnic persecution and eventually defecting to Turkey, which paid $1,000,000 to release him from prior citizenship claims.) Greenspan depicts their competition as a thrilling, methodical back-and-forth, with each one upping the weight count and trying to outdo the other. The nineties flavor is perhaps at its highest ebb when discussing Michelle Smith, a controversial Irish swimmer who so radically improved her physique and timing in a span of several years that she was widely suspected of cheating; it didn't help that the improvement took place under the training of husband Erik DeBruin, who disgraced his own athletic career by doping. (Although Smith would later be suspended for tampering with a random drug test, she was never caught cheating during competition and she retains her '96 medals.) At one point, Smith tells us, she received a visit from none other than President Bill Clinton - a ubiquitous presence during these election year games - who congratulated her on her victory and for withstanding the media onslaught.

The biggest story of these weeks is also one of the most indicative of this whole period, given both the right-wing plotter responsible for it and the cruel mass media harassment of the ordinary security guard who tried to thwart it. However, the event is mentioned only briefly; Greenspan tactfully nods to the deadly terrorist bombing of the Centennial Olympic Park on July 27 but defers to the IOC president's statement, echoing the 1972 hostage crisis, that "the games must go on." Though not as routinely backward-glancing as, say, Greenspan's 2004 film, there is definitely a sense of history at play throughout - starting with Muhammad Ali himself lighting the Olympic torch with a hand trembling from Parkinson's. For several of the most prominent athletes, the Atlanta games form a bracket with L.A. '84 and if there's often a sense of distinct eras within Olympic history (as I've already noted with the mid-zeroes to mid-teens period dominated by Usain Bolt and Michael Phelps), then '96 may be more of a culmination than a new beginning. It also functions as a transitional midpoint within a larger history; situated, like the giddy 2000 games, halfway between the tense bipolar conflict defining the Olympics for half a century and the new chaotic and embittered international landscape of the present. By the time this special finally aired a year and a half after it was shot, I suppose there were aspects of the mid-nineties zeitgeist that already felt dated. This might explain why, despite the time capsule quality of Atlanta's Olympic Glory, there is one gaping hole in its depiction of the summer of 1996: not a single participant or spectator is seen performing the Macarena.

White Vertigo, dir. Giorgio Ferroni

Winter 1956 - Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy

When I saw that the late fifties winter documentary would be in color, I was initially a little disappointed. The high contrast of black and white has been so fitting for the snow and ice sports of these games that I was sorry to see the format go. That regret evaporated instantly upon the very first frame of White Vertigo, whose opening sequence is easily my favorite passage in any Olympics film I've watched thus far. It has nothing to do with the main event until its final moments, as a skier descends the freshly crowned slopes, his Olympic torch held aloft and illuminating the tracks below his skis with a warm orange glow. Before then, the first ten minutes are consumed by the end of autumn in a quiet Italian village. The gorgeously rendered palette is brown and gray, a potentially dull spectrum conveyed with exquisite sensitivity in breathtaking compositions. Ferroni employed Aldo Scavarda, a first-time director of photography who would shoot L'Avventura in a few years, setting the standard for sixties cinema. Here he meticulously follows the onset of winter in the old-fashioned rustic community, melancholy and full of longing until the first snowfall brightens the mood and completes the effect. (The Criterion Channel account, knowing what they had in their possession, highlighted screenshots from White Vertigo in a Twitter thread during the last Winter Olympics.)

The rest of the documentary follows a more conventional approach, albeit with some delightful experimentation thrown into the mix. Building on previous depictions of ski jumpers (especially in the '36 German Youth of the World), the film leaps deliriously between midair shots of the soaring athletes in order to sustain their collective flight. Most notably, Ferroni crosscuts between different events to set up both parallels and contrasts, the latter quality underscored (literally) by shifts in music. The earliest example alternates between a gliding speedskater to the beat of an aloof jazzy piano roll and swerving slalom racer wrapped in a classic serenade of harp and strings. The shift in fifties mood is notable not just in the bold Eastmancolor flourishes and the rhythms of modern jazz, but also by moments like the lights on the sleek new stadium flashing on before a hockey match - we are suddenly a long way from the Old World charms featured in the opening montage. The sensation is much like wandering in Disneyland (which had just opened the year before) from the medieval European stylings of Fantasyland to the sleek proto-Space Age design of Tomorrowland. The weary rigidity and anxiety of the early Cold War era has given way to a fresh, restless energy, with the narrator himself marveling that these friendly competitors, quite chummy outside of the arena, would have been mortal enemies just a few years earlier. Even the Soviets - eight months shy of ruining some of this newfound goodwill with the invasion of Hungary - are now in the mix, with rival Finns always nipping at their heels (especially during the grueling cross-country races), sometimes pulling ahead in the end. And is that Sophia Loren smiling away in the crowd? Yes, the filmmakers are quite happy to confirm.

A mere forty years now separates my summer and winter coverage, a gap that once spanned nearly an entire century. The next round-up will bring the events even closer together as we explore the sunny eighties (Barcelona 1992 giving way to Seoul 1988, Los Angeles 1984, and Moscow 1980) and the snowy sixties (Squaw Valley 1960, Innsbruck 1964, and Grenoble 1968). Because this entry was delayed for so long - it was originally planned for September - I'm obviously abandoning the monthly schedule and moving to a weekly approach instead. (I'm writing these words a dozen days ahead of publication, so no worries - I've got a good backlog going or you wouldn't be reading this.) See you next Wednesday.

No comments:

Post a Comment