for the introduction & line-up of monthly capsules

running from August 2021 to February 2022

A Turning Point, dir. Kim Takal

Winter 1984 - Sarajevo, Yugoslavia

This was the first Olympics of my lifetime (three months after I was born), but the world onscreen is one I have almost no memory of. As with the summer documentaries already discussed, A Turning Point plunges us into the heart of eighties fashion. The welcome committee's uniforms are described as "futuristic" which I suppose they are, in a paradoxically very retro sense: puffy vests, headbands, high boots. It's the Jetsons meets Jefferson Starship on ice - the kitsch levels are, endearingly, off the charts. The athletes themselves are not spared. As I illustrated in this Twitter thread, the national outfits look increasingly ridiculous as the opening parade carries on. First, the Czechoslovakian delegation in normal, even subdued winter overcoats; Canada in slightly more pronounced but still tasteful red-and-white coats and hats; the USSR wrapped in some rather ostentatious scarfs; Great Britain with bulky headgear atop all the ladies; the Americans zipped up into awkward puffy cowboy-in-winter outfits (appropriately, the translation of U.S.A. is S.A.D., carried in front of the delegation by a puffy, zany-costumed representative, in an image that looks like it's ripped straight out of Dr. Suess). Finally, most amusingly, the host country emerges last, Yugoslavs dressed in tightly-belted light gray trenchcoats and blue fedoras, looking for all the world like an army of Inspector Gadgets. The soundtrack feels charmingly dated as well, scored electronically like the last couple winter films but this time with a decidedly pop rather than rock bent. For narration, we're offered the warm, enthusiastic but authoritative tone of David Perry (brother of Bud Greenspan, who'd direct the same year's summer documentary, which Perry also narrated) in a manner that evokes TV specials and film trailers of the era.

More than any other documentary I've watched, A Turning Point attempts to provide the audience with a digest form of how the games actually unfolded, proceeding day by day and cutting back and forth between events according to schedule: we watch the scoreboard change with each finish as if we are processing the outcome in real time. While many other films stuck to chronology for the most part, this one really emphasizes the specific itinerary and groups events together by when they occurred rather than by sport (the film also takes note of events that don't occur, such as the men's downhill races delayed day after day by brutal snowstorms). The emphasis is very much on the individual athletes - their goals, results, and particular rivalries and benchmarks, but despite Perry's presence we're not yet in the Greenspan era. The net is cast much more broadly than in Greenspan's films and while athlete interviews are peppered throughout, they usually take place in the midst of a crowd just before or after a given event, rather than a subsequent, reflective talking head set-up. Takal pays particular attention to the Mahre brothers, fraternal (but near identical-looking) twins who place first and second in the slalom, and explains the dueling claims and personalities of the Austrian, Swiss, and American contenders for downhill medals. Scott Hamilton, a figure skater on the brink of retirement, is a crowd favorite; cheering him on, American fans get to hold aloft the Uncle Sam-booting-Russian bear banner that we saw in 1980, compensation for the U.S. hockey team getting knocked out in the first round (the Soviets, never even having to face off against their American rivals again, cruised to a comeback this year). The only miracles on ice in '84 would occur in the graceful swirls of the figure skaters, most notably the widely acclaimed dance of British pair Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean, rather than the rough-and-tumble of a hockey match.

The movie, like the '80 Lake Placid doc, has an air of a sponsored promotion (I don't know if Mitsubishi paid for product placement - it did sponsor the games themselves - but Takal's camera certainly lingers over every opportunity to feature the corporate insignia). Also like the last film, and quite unlike the '72 and '76 films, we're back to a TV aspect ratio rather than sweeping CinemaScope. This visual shift, plus the more cluttered and weather-beaten Yugoslavian locales, give A Turning Point a less expansive air; everything feels a little more crowded. Takal pays close attention to the cultural milieu surrounding the communist but not Soviet-aligned society's Olympic presentation. These often consist of committees standing before a microphone - in one case, led by Liv Ullmann in a tribute to UNICEF. Witnessing the crowds of children there and elsewhere becomes a poignant experience in retrospect - A Turning Point interviews many youngsters who are excited to have the world arrive on their backyard. All of these cheerful kids are in for an imminent rude awakening. The Sarajevo games were held almost seventy years after the city spawned World War I (with the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand) and less than a decade after this joyous celebration, Yugoslavia would shatter, leaving behind battling national and religious factions. Civil war, ethnic cleansing, and NATO bombs came to define the nineties, transforming this proud modern metropolis into the scene of the worst bloodletting on European soil since World War II. This was certainly not the future foreseen by anyone in the winter of '84, when silver medalist Jure Franko becomes a national hero as the first Yugoslavian to place in a winter event, and the film does not even bother to tell us his ethnicity.

Tokyo Olympiad, dir. Kon Ichikawa

Sensation of the Century, prod. Taguchi Suketaro & supervisor: Nobumasa Kawamoto

Summer 1964 - Tokyo, Japan

If eighties Yugoslavia had its chance to show off before descending into wartorn rubble, twenty years earlier Japan was able to stage a tribute to peaceful coexistence after the devastation of war. Tokyo Olympiad does not exactly shy away from the legacy of World War II. The Olympic torch relay travels through still-shattered sections of Hiroshima; during the opening credits, when the narrator intones every single year and location of all modern Summer Olympics, he mentions that the event had to be skipped in 1940 but does not say where where it was supposed to be held: Tokyo. Japanese officials were eager to promote national pride in their postwar recovery, so they took an unprecedented step while planning the cinematic commemoration. Up to this point in history, Olympic committees usually chose established sports documentarians or lesser-known filmmakers to helm the accompanying film, but Tokyo Olympiad was initially offered to none other than Akira Kurosawa himself - not just the biggest name in the Japanese film industry but one of the most acclaimed directors in the world. Kurosawa was a little too big, in fact, demanding a then-huge budget of over a million dollars and even control of the opening and closing ceremonies. (Interestingly, many years later cinematic auteurs like Zhang Yimou and Danny Boyle would be tapped to stage ambitious live opens and closes to the games but not the accompanying films.) So Kon Ichikawa, no slouch given recent triumphs like The Burmese Harp and Fire on the Plains, was tapped instead.

If Ichikawa would not drain their pocketbooks, he would exhaust his patrons' patience in other ways. The filmmaker was less interested in extolling national pride and meticulously documenting the events than in exploring the human element and carving out arresting, often almost abstract images. Although many sports are featured, often from unconventional angles (during the shot put, we cut to black-and-white extreme close-ups of the ball splashing into rain-soaked mud), some of the film's most memorable passages are far afield from what organizers hoped to highlight. After an intermission, the second half introduces us to Ahmed Issa, part of a two-man delegation from the brand new nation of Chad. Wincing in the bright lights and mostly keeping to himself, Issa is shown dining by himself and pacing the track with a sweatshirt over his head as Japanese athletes pass him in the other direction; it's Issa that Ichikawa is interested in, not them. And why? Not because of athletic accomplishments...Issa fails to even qualify for the final round of the 800m. Instead, Ichikawa is intrigued by the quiet, obscure athlete's lonely composure. Describing his past (a father who was a tribal chieftain died of smallpox) and hopeful future (he plans to teach physical education), the director brings us closer to this easily-overlooked individual, but not too close. Issa is never interviewed and the narrator is more speculative than confident about his inner state. After winning a bronze medal in the '65 All-Africa Games, the runner would return to the Olympics in '68 where he also failed to advance beyond the semifinals. Then history loses sight of him, with the only online record of his death listing the year 1983 but no date.

In addition to this unusual sketch of a competitor, almost a short film embedded within the larger tapestry, Ichikawa pays close attention to spectators and judges - figures who are often obscured in Olympic films. He shoots officials climbing up to their seats from underneath the stands, captures offscreen teenagers chanting for their colleague, and utilizes close-ups of children delighting in their first brushes with the larger world as a torchbearer races past. He also, of course, follows the individual heats closely (a sequence on swimmers is the most conventional of these presentations) often alternating between striking, off-center compositions full of empty space and extreme, almost microscopic shots of eyes, mouths, or antsy feet. When he visits a shooting competition, the edges of the men's faces appear starkly against pitch-black backgrounds. We often aren't told the athlete's names or what the stakes are in a given moment, although Ichikawa does end the movie by spending long, quiet minutes with a single figure: Abebe Bikila, the Ethiopian who - without breaking his stride - finished the marathon several minutes out of sight of his nearest rival. Holding his face in profile as the blurred crowd passes behind him, the film facilitates both immersion and contemplation, opening doors but never pushing us through them. (Recall that I've already discussed Ichikawa's work in "The Fastest" segment of Visions of Eight in which he isolated each 100m runner in turn, for a series of slow-motion meditations.)

Tokyo Olympiad's arresting form contributes to its reputation as perhaps the best Olympic documentary - only Leni Riefenstahl's Olympia comes closes. However, Olympic historian Peter Cowie quotes a government minister who was in charge of the project and complained that it "overemphasized artistic aspects, and I do not believe it is a proper record of the event." Sensation of the Century was the Japanese committee's answer to this dilemma, an extensively re-edited version of Olympiad that runs only a little bit shorter but strikes a very different note by using many alternate shots (usually more conventional wide angles to take in all the action), a more uplifting score, and a far more thorough use of wall-to-wall narration and titles so that we're never left in the dark about who is competing and where that competition stands. For the most part, this feels redundant although it's helpful for sports historians and those who were confused about certain events in Ichikawa's version. The film is also much more overtly nationalistic, emphasizing Japanese athletes and medal counts wherever possible. Both movies hit many of the same notes in terms of the games' standouts. The captivating pole vault face-off between Fred Hansen and Wolfgang Reinhardt extends nine hours, from balmy afternoon to the dark of night. Plucky British schoolteacher Ann Turner comes from far behind to win the 800m by several lengths. And Billy Mills, a Lakota orphan raised on a reservation and then in a residential boarding school (and at this time a lieutenant in the Marines) pulls off an extraordinary victory in the 10,000m. Incidentally, though it's not part of either film, an American TV announcer was so excited by Mills' final kick that he started screaming, over the voice of the lead man (who was ignoring this turn of events) "Look at Mills! Look at Mills!", and was fired by NBC for stepping out of line.

Moving backwards, it feels to me like the summer games are crossing an invisible bridge, into a more distinctly remote past. There are only a few boomers present, all in their late teens (we're just on the cusp of their dominant era, which would peak in the mid-eighties and mostly disappear in the first few Olympics of the twenty-first century). But in addition to the obvious pre-sixties counterculture milieu, some of the events simply look different than they do today. This is the first time I've seen pole vaulters and high jumpers landing in a messy pit full of sawdust and wood chips rather than a foam mat. And with Dick Fosbury still four years in the future, those high jumpers are all leaping sideways over the bar - no "Fosbury flop" in sight. On the other hand, this was an Olympics of many firsts - the first appearance of a whopping sixteen countries (many of them new post-colonial nations), the first time South Africa was excluded for refusing to send a multiracial delegation, the first games held in Asia. This is also, I'd guess, the first Olympics with little to no significant presence of World War II veterans in the competition. The wrecking ball which opens Tokyo Olympiad, smashing into a delipidated old building to make way for the gleaming stadium, could be seen as the final punctuation on the postwar period - an acknowledgment of what came before as well as what's on the horizon. That wrecking ball is nowhere to be found in the Sensation re-edit; nor, for that matter, is Issa from Chad.

Calgary '88: 16 Days of Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Winter 1988 - Calgary, Alberta (Canada)

Here begins the winter reign of Bud Greenspan - or rather, our first hint of his reign (someone else will direct the next documentary, but he'll be back for '94 and every four years after that until his death in 2010). This is a welcome introduction, because since the high points of Sapporo Winter Olympics and the one-off gimmick White Rock in the seventies, the winter films have been struggling. The less-than-half-hour '80 offering was more of music montage, and while '84 went more in-depth, both felt a bit more like glossy promotional videos than proper movies. By contrast, Greenspan's coverage of the less-celebrated winter events is as expansive his summer debut four years earlier in L.A., running well over three hours. He immediately whips the material into ship by organizing it into his favorite format: individual stories of triumph and disappointment, one-by-one, offering a very human insight into the various events. I've seen some grumbling about his adherence to formula and hegemony over Olympic cinema for two decades. This trepidation may be somewhat understandable in relation to the summer games - in which there's a massive expanse of events and terrains to focus on, fostering a tradition of auteurist innovation and variety (to be fair, Greenspan only helmed four of those films - with just three, from 1996 to 2004, in a row). In winter, however, despite the seventies 'Scope era, the range of options for both narrative and style tend to be more limited. So zooming in on the athletes - with hundreds of options and massive turnover after each installment - offers an endless storytelling buffet.

Calgary '88, after a celebratory opening tribute the Canada's vast expanse and cultural pride (and aside from a few brief action-oriented musical montages), is split into the following chapters: the Quebecois Gaetan Boucher, seeking in vain to echo Sarajevo gold in speedskating as his deeply emotional parents cheer and then weep in the grandstands (Greenspan loves opening with a noble past-his-prime loser); the hope-disappointment-comeback arc of the Swedish cross-country team; supposedly reformed bad boy Matti Nykanen's ski jump sweep; the male figure-skating "battle of the Brians" between an American and Canadian star; the dominance of a Dutch female speedskater over the East Germans (in their last trip to an Olympics); the struggle of an Austrian to stay on the medal podium as his rivals set new records in the downhill race; personnel issues among the East German bobsledders trying to upset the Soviets; one of the film's most unvarnished success stories as a poetic-minded, woods-loving Swede speedskates to record-setting times in the long distance competitions; and the climactic contest between gold medalist Katarina Witt (the first two-year winner since Sonja Henie) and disappointed bronze medalist Debi Thomas - both dancing to passages from the opera Carmen - while Canadian darling Elizabeth Manley sneaks in between to steal silver and the audience's hearts. Though Thomas' drama is the most compelling, and Manley's performance the most exciting, Witt has an arresting, uber-cinematic aura that captures the camera in close-up, creating some of the film's most striking slow motion shots.

Perhaps the most famous of the film's untold stories, at least for millennials who grew up on Disney films during the following decade, is the Jamaican bobsled team depicted in 1993's Cool Runnings. Although the narrator never mentions them, look closely and you can spot their bright green and yellow jackets among the more traditional competitors. Other athletes have had interesting afterstories: Witt, fitting the impression she makes here, would move into cinema, appearing in nineties classics like Jerry Maguire and Ronin (in which she plays the skater unknowingly targeted by a sniper in the middle of her performance). The two Brians, Orser and Baitano, would eventually make news by coming out as gay (the Canadian Orser in the midst of a patrimony case in the mid-nineties, the American Boitano in order to make a statement against homophobic Russian policy before the Sochi games in 2014). As for ski-jumping rebel Nykanen, shown holding his newborn infant and telling us he's a new man after getting arrested and kicked off his team multiple times...if you want a happy ending, stick to the movie. I suspected his redemption arc wouldn't turn out quite so clean-cut as he, his coach, and the director would like us to believe, but it's worse than I could have possibly imagined. A quick internet search reveals that he'd divorce his new wife that very year, go on to an additional five marriages and four divorces, become a stripper in the nineties and porn star, and then face an endless stream of arrests, charges, and convictions for assault and other violent crimes resulting in fifteen divorce requests from his battered wife (two of them carried through, since she married him twice). Perhaps he finally found peace - and let others have theirs - in his later years (as a dramatic obituary suggests), recording music and a cooking show before dying suddenly in his mid-fifties. Either way, Calgary '88 suggests that his only equilibrium was achieved mid-air, briefly suspended above the earth where he caught so much trouble.

The Grand Olympics, dir. Romolo Marcellini

Summer 1960 - Rome, Italy

This was the perfect year to hold a Roman Olympics, with La Dolce Vita's caustic if gleeful celebration of the Eternal City causing a sensation around the world. The Via Veneto was at its peak as a magnet for chic, cosmopolitan globetrotters and Italy had clearly bounced back from its post-Mussolini blues. However, both the '60 games themselves and the film commissioned to commemorate them were more preoccupied with Rome's ancient glory than its modern amenities. Although sleek new facilities were built for the occasion, many events were staged inside of millennia-old ruins: for example, Greco-Roman wrestlers appropriately tussled inside imperial basilica while gymnasts leaped and tumbled against the backdrop of public baths (in a surreal juxtaposition, the great heavy stone walls were topped with a billowing, paneled roof). Most memorably of all, our old - or rather, four-years-younger - friend Abebe Bikila wins his first marathon, racing barefoot into the night, calmly and coolly outpacing his competitors as bright bulbs illuminate the scenic landscapes behind them. "I wonder what this Ethiopian's name is?" the narrator knowingly teases us at the starting line. "Everyone knows no one can beat [Czechoslovakian '52 champ Emil] Zatopek's time." Although Ichikawa would find his own way to immortalize Bilkila's tempo (sticking with long, immersive close-ups keeping his pace), Marcellini's sequence is just as effective, this time through brisk cutting, excited narration, and mobile wide shots capturing the unusual nature of this into-the-night run. This was possibly the last time that the runners would not finish at the stadium; Bilkila, the first black African to win a gold medal, celebrates in front of flashing cameras and adoring spectators - they'll remember his name now - under the aged Arch of Constantine.

The Grand Olympics does make time for some contemporary portraiture amidst its longer historical sweep. There's a fascinating montage of the athletes at rest and play in the Olympic Village, scored to boisterous rock 'n' roll and lubricated by glass bottles of Coca Cola. All races and nationalities enjoyed the youth culture of the period, which had its roots in America and was now blossoming everywhere among restless postwar generations. Though not in Cinemascope nor rendered in quite so vivid a color palette as the next couple summer documentaries, this film does have a late fifties/early sixties big screen feel with its relatively wide 1.66:1 aspect ratio and sweeping overhead helicopter shots approaching landmarks like the Coliseum. According to Peter Cowie and others, this is the first Olympic doc to make such extensive use of a telephoto lens, getting us closer to the action (although having watched the later films first, it feels like we are a bit more distanced then, say, Visions of Eight would bring us). Technology even contributes to the drama. In a proto-Blow Up moment, the filmmakers utilize an editor's eye to capture a secret embedded in the relay race, missed by the judges but presented to us through slow motion and freeze-frame: the third place Germans should actually have been disqualified for a late hand-off. As far as its tone and focus goes, the film does not simply adhere to a strict nationalistic view - many non-Italian competitors are centered - but it does indulge in every form of national stereotype you can imagine. Every Russian has been plucked from the snows of Siberia, American players cutting a basketball are "scalping", and cringey Rudyard Kipling references are hurled at the audience almost as rapidly as the ball itself during an India vs. Pakistan field hockey match. The narrator is irreverent but nonetheless admiring: there's no shortage of standout accomplishments and memorable figures to admire.

Although some viewers are disappointed by the brevity of athletes' backstories, my own admitted ignorance of these competitors made each individual tale a surprising delight. Highlights include the odd couple of American Rafer Johnson and Taiwanese Yang Chuan-Kwang, friends who competed and finally embraced in the decathlon; the hot and sweaty cycling contest - as much mind game as physical exertion - between Italian baker Livio Trape and Soviet engineer Viktor Kapitonov (a cyclist died, offscreen I think, amidst this race); and most of all, the amazing sprinter Wilma Rudolph, a handicapped child from a poor family with nearly a couple dozen siblings, who couldn't walk until she was seven but broke world records at twenty. My father, who was twelve in 1960, recalls reading Rudolph's biography in an inspirational comic book. There is, however, one very disappointing absence. I've previously mentioned how probably the three most famous American Olympians are Jenner, Ali, and Owens. One of those athletes is present in The Grand Olympics...a middle-aged Jesse Owens watches Ralph Boston finally break his long jump record. But that's it. Considering these were the games that kickstarted the boxing career of Muhammad Ali (before he was Muhammad Ali) with a heavyweight gold, and that the documentary does take time out for boxing champions (but only the lighter-weight Italians), the oversight is regrettable. I guess no one really knew what they had until he knocked out Sonny Liston four years later. If one sixties icon isn't present, another - Pope John XIII, who would soon initiate the cultural earthquake of Vatican II - is available to bless the games. And this is the second Olympic film to feature a cutaway to Bing Crosby, who also showed up to gawk in the Californian snow for the 1960 winter games.

One Light, One World, dir. Joe Jay Jalbert & R. Douglas Copsey

Winter 1992 - Albertville, France

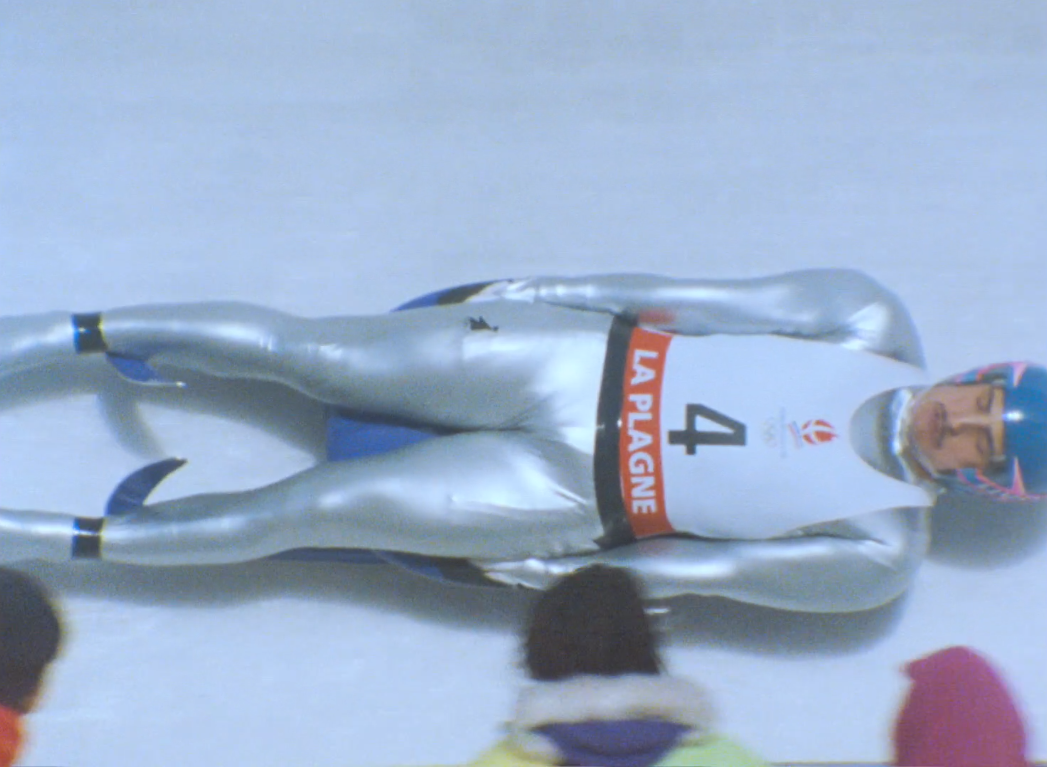

For the first time since summer in Barcelona (at the outset of the third round-up), I'm discussing a film which coincides with my own personal viewing history. I was eight years old when Albertville provided my introduction to the Olympics. Without recalling many specifics - I thought this was Dan Jansen's year but apparently that was next time - I mostly remember feeling enraptured by the striking scenery and the fast-paced excitement of the sledding, speedskating, and downhill skiing events, especially true in '92 given the introduction of the bumpy-ride ski mogul and crowded-field short track speedskating. When the summer games followed half a year later, I was mildly disappointed that the sports seemed less evocative of a particular season - they weren't as shaped by outdoor features as the winter games - and that a footrace or basketball game lacked the sleek visual dazzle of a bobsled run or ski jump. One Light, One World mixes 16mm and varying-quality video in order to capture that need for speed from all angles and in all conditions. One of the most striking sequences zooms in on luge drivers while their bodies swoop horizontally past spectators in the track's foreground, and the narrator makes special note of a new ski-jumping technique - spreading the tips into a V-shape - to gain speed and distance. But it's not just physical exertion that gets the filmmakers' attention. A unique passage is set aside for athletes to discuss their spirituality and how it shapes their performance and peace of mind, using a medieval village up in the mountains above Albertville as an evocative backdrop.

This concept of a metaphorical light glowing within, in addition to the literal Olympic torch, provides the "One Light" part of the title. The film even opens with an ordinary French teenager awakening early, zipping up her snowsuit, and stepping out onto the street as part of the torch relay in the countryside. As for "One World," this is given voice by beloved American figure skater Kristi Yamiguchi, who wistfully hopes these games can cohere a global community after observing that certain unnamed countries have just recently collapsed. She is obviously referring to the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, states that ceased to exist mere weeks before the Winter Olympics, after surviving for seventy-five years. As in Barcelona that summer, the ex-Soviets - frequently described by the narrator simply as "Russians" - were caught off guard and improvised by competing as the Unified Team (aside from the newly independent Baltic republics who preferred to go it alone). The early nineties was also a moment when the sixties generation was emerging into full-on leadership roles. This is represented onscreen by Jean-Claude Killy, the skiing legend whom we recognize from the two '68 documentaries, now heading the French Olympic committee. Albertville welcomed the first Olympics in France since that fateful year, and moody footage from the Grenoble games is often sampled as a reference point. That decade's zeitgeist is also expressed by extreme and improvisational "freestyle" aerial and ballet skiing, which the narrator informs us was "born out of the revolutionary American lifestyle of the 1960s." Aside from moguls, these new ski events were not yet part of official competition, but they were permitted as demonstrations (speedsking was also a demonstration sport...still no snowboarding though).

Jalbert, who got his start in filmmaking as technical advisor and stunt man on the Robert Redford ski film Downhill Racer (speaking of sixties influences), produced the Sarajevo documentary. One Light, One World often evokes that earlier work in its breathless narration and wall-to-wall music, this time wailing rock guitar and mystic new age rather than keyboard pop. There are more talking head interviews now, perhaps inspired by Greenspan's seminal work four years earlier, although Jalbert employs these commentaries mostly as punctuation for the events themselves. He does not carve up the narrative into the standalone individual stories that defined Calgary '88. Nonetheless, certain athletes do emerge to focus our attention on particular competitions. We're encouraged to root for '88 speedskating champ Bonnie Blair with frequent cutaways to her elderly mother (very much a Greenspan touch); mogul gold medalist Donna Weinbrecht watches her friend and rival Raphaelle Monod collapse with mixed emotions; and Alberto Tomba's thrilling, risky acceleration in the second half of the slalom, after he sensed himself falling behind, is narrated for us by no less a luminary than Killy. The climax of the film, as with Calgary, is reserved for figure skating with two Americans emerging on the female singles podium. Gold medalist Yamuguchi may be the only '92 star who I remember as a big name among my schoolmates at the time - with the exception of bronze medalist Nancy Kerrigan (for reasons unrelated to this particular Olympics). You never know what an Olympic film will choose to include or exclude, but I'm pretty sure we'll be hearing about Kerrigan again.

Olympic Games, 1956, dir. Peter Whitchurch

The Melbourne Rendez-vous, dir. Rene Lucot

Alain Mimoun, dir. Louis Gueguen

Summer 1956 - Melbourne, Australia

+ bonus on equestrian events in Stockholm, Sweden: The Horse in Focus

There are a number of unique features about the '56 Summer Olympics. This is almost literally true in the cinematic sense, since four films were produced (albeit only one full-length feature, accompanied by a midsize documentary and two shorts). Only Seoul '88 rivals that record, and one of its four films merely compiles footage from the other three. Another unique quality was due to the equestrian events, held half a year earlier in Sweden due to Australia's complicated horse quarantine rules. These were the first games - of either season - hosted outside of Europe or the U.S., and also the first to unfold in the southern hemisphere. This caused some scheduling complications. After all, Australia observes summer when most Olympic competitors experience winter. Often in later years, even in host countries above the equator, the "Summer" Olympics would take place in September or even October. This time, however, the IOC pushed it all the way back to November 22 - December 8. Still not quite winter (this was technically Australia's late spring) but closer to the mark than a July date would have been, the timing makes for some delightful incongruities. In The Melbourne Rendez-vous, we watch a couple young Singaporian athletes giggle at window displays of Santa participating in summer, rather than winter, Olympic games, swinging the shot put in a warm, grassy stadium as his reindeer cheer him on. This is part of a larger pattern in that film, which frequently breaks from the competition to linger on also-rans who've already been eliminated but are now free to enjoy the lush scenery as tourists.

This adventurous, wandering eye is typical of Rendez-vous, a French film equal parts sports doc and travelogue. It's the longest of the quartet and the most inventive. By contrast, Olympic Games, 1956 is as straightforward a depiction as its title suggests, running sixty minutes and consisting mostly of athletic action and an announcer-like narration (with a lengthy, almost country-by-country breakdown of the Opening Ceremony parade). This could be tedious and redundant if viewed after the more expansive Rendez-vous, but Criterion wisely places it first. As such, it provides an enjoyable introduction to the games, allowing immersion into the events themselves - albeit from a distance, lacking the extensive telephoto observations of later films, similar to how the breadth of the field would be presented on television but with the helpful assistance of writers who know what's going to happen next. The camera follows runners round and round the track as we're told to focus on particular participants and watch them advance or fall back, an approach most striking in the come-from-way-behind triumph of the Irishman Ron Delaney in the 1500. Twenty-year-old Al Oerter - looking slimmer and more youthful than the version we've already seen in later games - surprises spectators by beating European favorites for his first of four gold medals in the discus throw, a streak extending all the way to '68. And there's much attention paid to Shirley Strickland, a hometown favorite who won two golds in the hurdles and relay.

Strickland is introduced early in Rendez-vous, snipping her roses and playing with her toddler in a lovely suburban home while international flights soar overhead. Director Rene Lucot is fascinated by these contrasts, and by the simultaneous wild exoticism and familiar domesticity of Australia about which he waxes lyrically over images of koalas, kangaroos, and the ordinary brick-and-mortar neighborhoods of the usually sleepy, suddenly bustling Melbourne. The French voiceover also exhibits the requisite horniness we've come to expect from older Olympic movies (especially the French ones), with endless commentary on the female figure and even advice that perhaps one of the shot-putters should slim down her figure to be more "lovely." This condescension includes an overtly ogling, lascivious montage of female athletes stripping out of their warm-up outfits in front of the stadium crowd - perhaps the most cringeworthy passage in any selection thus far (though a female filmmaker herself may provide some competition of a very different kind when we rewind another twenty years). In other moments, the filmmaker's affectionate if teasing interest in his subjects is more endearing. This is, for better and worse, an unusually reflective entry in the canon (Cowie calls it "more observant and more inquiring") with some gorgeous photography including dawn on a black swan-studded lake which long rowboats will interrupt for perhaps the only time in centuries.

The closing ceremony that ends both Rendez-vous and Olympic Games emphasizes the coming together of different nations: this was the first time athletes from around the world marched together in a cheerfully disorganized crowd, a tradition that would continue to the present. Curiously, it's the more focused and staid Olympic Games film that observes (without naming) the global conflicts catalyzing '56 via black-and-white footage of guns firing at sea. The Suez Canal crisis and Soviet repression of Hungary affected the games in a handful of modest boycotts: Egypt, Iraq, Cambodia, and Libya due to the former; Israel, the UK, and France due to the latter. Communist China also began a longstanding protest of Taiwan's recognition as "the Republic of China". Tensions ran so high during the games that a full-on brawl emerged when the Soviet Union and Hungary faced one another in water polo - an incident not captured in either of the main movies unless I missed it - and the police had to be called in to get the match back on track (at least Hungary eventually won that particular confrontation). Another ongoing conflict, which did not affect the Olympics as directly as these others, was the Algerian War. The complications of an anticolonial rebellion in a country that was officially considered a part of France were exemplified by the figure of Alain Mimoun, the determined thirty-five-year-old living meagerly in Paris, who unexpectedly beat defending champion Emile Zatopek in the marathon.

Mimoun's triumph climaxes both Rendez-vous and Olympic Games but comes most sharply into focus in Alain Mimoun, a clever biopic that combines documentary footage of his Olympic race and past competitions with re-enactments in which Mimoun plays himself (even covering his moustache with unconvincing makeup to invoke his days as a young soldier). Photographed in crisp black and white unlike the other '56 Olympic films, the short leads us from his early days as an accidental athlete through his traumatic World War II experiences, the humble working-class day jobs that funded his amateur career, and even the birth of his daughter half a world away as he stays in the Olympic Village. The war passage is particularly striking - his golden foot was nearly amputated on an Italian battlefield, before German fire forced an evacuation and a medical reconsideration. As for that other war, the Algerian one, the film does not mention it, but several years later Mimoun would announce himself to Charles De Gaulle with a full salute: "Born in Algeria, but forever French." Unfortunately, as Pat Butcher's biography The Destiny of Alain Mimoun relates, "To the French, Mimoun is Algerian. To the Algerians, Mimoun is French." Nonetheless, he remains an athletic icon for both countries, living to ninety-two and carrying the torch through Paris in its 2004 journey back to Athens.

Finally, Criterion presents The Horse in Focus, necessary for the sake of completionism not just for horse lovers but because the Stockholm Equestrian Olympics had its own distinct promotions (see that striking poster above), torch relay, and opening ceremony that even the Queen of England - who ghosted her own Commonwealth host nation later that year - attended. With good reason: her own horse was one of the competitors. By her side, and present alone to open the Melbourne games as well, is the Duke of Edinburgh who died at ninety-nine less than a year ago looking, admittedly, a bit worse for wear than the dashing figure he cuts here in his thirties. The brisk Swedish narrator details the ins and outs of the various competitions - dressage, show jumping, and eventing - and the film has an alluring, curiously autumnal feel with its stately fields and old brick stadium, left over from the 1912 games (which we'll eventually reach as this series winds down). This offers a relaxing coda for one of the busiest chapters in Olympic cinema history.

Lillehammer '94: 16 Days of Glory, dir. Bud Greenspan

Winter 1994 - Lillehammer, Norway

While 1992 introduced me to the Olympics and created an overall impression of the winter sports, I can recall the Lillehammer '94 games in greater detail, from the vivid Norwegian scenery to the spindly stick figure iconography to the larger-than-life personalities involved. The Nancy Kerrigan/Tonya Harding drama, in which Harding's bungling associates (with or without her knowledge) attacked and injured Kerrigan during her figure-skating trials, remains to this day the biggest Olympic scandal I've ever witnessed - this was the height of the tabloid nineties, with the O.J. Simpson case just months away. On a less sordid note, speedskater Dan Jansen's miraculous comeback provided the perfect material for Greenspan, given his taste for suspenseful, heartstring-plucking stories of athletic struggle. Though it took this film to remind me of the specifics, I've always retained the broad outline in memory: personal tragedy, fateful accidents on the ice, impossible odds, impending retirement. Back at Calgary in '88, Jansen vowed to win gold in honor of his sister Jane who died hours before his heat. Instead he slipped on the ice in both of the races he was expected to win, and four years later in Albertville he failed to medal - coming in fourth just as he had in his debut at nineteen in Sarajevo.

Despite world records and championships, Jansen could never seal the deal on the biggest international stage of all. The 500m in '94, his fourth and final Olympic appearance, was supposed to be his redemption tale but when his skate skidded on a corner he lost a few hundredths of a second and fell out of contention. All the remained was the 1000m, an event where Jansen was so weak that he almost considered dropping out rather than exiting on that note. Of course, he went ahead with the last race anyway. I still remember cheering Jansen on to his ecstatic, unexpected victory - not just gold, but a new record - when CBS aired the event (a live broadcast, I believe), following the biographical package they'd assembled to set his story up. Jansen's wife and baby daughter, named Jane after his lost sister, watched from the stands and afterwards he skated around the rink with the infant in his arms. A feel-good story that swept the nation that week, this race remains one of my formative sports memories, probably the only one unrelated to a New England franchise. This passage may be the crown jewel in Greenspan's assembly of mostly feel-good narratives (in other documentaries, he lingers longer on noble losers).

As always, he packs his three-and-a-half hour film tight. The introduction sets the stage with rough video images establish the magnificent Norwegian countryside through northern lights and Viking ships carrying the Olympic torch (the cauldron is eventually lit by a ski jumper after soaring through the air). From there, Greenspan moves through the following stories: "Espen the Eagle" facing down a cocky German competitor in an attempt to restore Norwegian ski-jumping glory after a long national absence from the podium and his own dismal performance at Albertville; the hardscrabble upbringing of Ukranian waif Oksana Baiul who overcomes injury to win gold under the tutelage of fellow '94 gold medalist Viktor Petrenko (Greenspan touches on the Kerrigan/Harding conflict only in passing, though he does include the infamous shot of Harding breaking into sobs as she skates up to the judges and points to her broken footwear); the admiring rivalry of Italian and Russian female cross-country skiers; Jansen's moving tale right in the film's middle; the inspiring fortitude of middle-aged Italian cross-country skier Maurilio de Zalt who endures the first leg of the relay despite his age and size; the distinctively red-suited Johann Koss' extraordinary record-setting run in distance speedskating; the juxtaposition of the German bobsledding juggernaut and Monaco's good-natured Prince Albert (not just the son of Grace Kelly, but grandson and nephew of previous Olympians), a royal who humbly drives his team to a fourth-from-last finish; superstar Alberto Tomba's disastrous slalom runs before a magnificent return for a hard-earned silver; Viktor Smirnov's cross-country triumph on behalf of newly independent Kazakhstan to the cheers of a vast Norwegian fanbase; and the quintessentially Midwestern Bonnie Blair - a feature of several winter documentaries now - who retires in glory as an extended cheering section celebrates from the sideline.

The contrast between Lillehammer and the previous Norwegian games, in Oslo, is striking (Greenspan includes occasional footage from the black-and-white '52 film throughout). That time, I noted how urban the setting felt, in contrast to the usual resort town vibe of the winter games, but Lillehammer strikes a much more enchantingly rural impression. Neither the opening nor closing ceremony gets as much attention as it might deserve - the glimpses of the costumes and light displays are mesmerizing but the intro and coda are brief for such a lengthy feature. Greenspan does make room for one significant moment from the opening, as the IOC president asks the crowd to stand for a moment of silence in honor of Sarajevo. Ten years after those cheerful games, the once-proud city had descended into brutal factional warfare and ethnic cleansing. I remember, for years, thinking that the first Olympics I watched in '92 was held in Sarajevo rather than Albertville; when I eventually discovered my mistake, I wondered why I'd been confused.

After viewing Lillehammer '94, it makes more sense: athletes and officials mention the city repeatedly (Koss runs a charitable operation in Lillehammer to help out desperate Bosnians), not just due to its current place in the news but because so many of the competitors got their starts there. Over and over, Greenspan shows raw video footage from '84 to introduce Jansen, Blair, and others (in their cases, as scrappy teenagers making their debuts the last time that speedskating was held on an outside rink). This is also the first time competitors can mark a decade's anniversary from Olympics to Olympics; in the late eighties, the IOC voted to stagger the two seasons beginning in '94 - resulting in the first "off-year" winter games (I recall Lillehammer as an unexpected treat two years ahead of schedule - savored especially as I only discovered the Olympics in its last "winter and summer the same year" incarnation). The ten-year mark lends an additional emphatic punctuation to the Sarajevo flashbacks, as well as offering an appropriate bookend to conclude my arbitrary round-up of reviews, which began this week in a country that no longer exists.

We'll return to Scandinavia - after Sweden and Norway, it's Finland's turn - to kick off next week's collection, this time for summer (Helsinki 1952 followed by London 1948 and the infamous Berlin 1936, alongside a bonus: newsreel glimpses of Los Angeles 1932). Winter will begin with another nineties Olympics I well remember (Nagano 1998 followed by Salt Lake City 2002 and Torino 2006). In addition to the notable appearance of Leni Riefenstahl, this next entry will be the most Bud Greenspan-heavy round-up since the second (which covered his run of summer documentaries for Atlanta, Sydney, and Athens) - this time due to his consistent winter output.

No comments:

Post a Comment