The IX Olympiad in Amsterdam

The Olympic Games, Amsterdam 1928, dir. Wilhelm Prager

Summer 1928 - Amsterdam, Netherlands

The Dutch games of the late twenties offered quite a few benchmarks. For the first time, a giant Olympic torch burned throughout the entire sixteen days (although Berlin would initiate the first torch relay in '36). Indeed, this was the first time the games lasted exactly sixteen days; this was also the first parade led by Greece and ending with the host. Although not featured in either documentary - that I noticed - Coca-Cola sponsored this Olympics as it would continue to through the present day, the Germans finally returned to competition after their decade-long post-World War I ban, and this was the first Olympiad after the retirement of Pierre de Coubertin, founding president of the International Olympic Committee. The 1928 Olympics even invented the universal white-on-blue parking symbol when it created an overflow lot for the influx of automobiles (the city only had a couple thousand spaces prior to the event). In other ways, however, this feels like the end of a particular era. A year before the Depression hit, despite the long shadow of the Great War, there's still a fresh air of rugged innocence about these games. Going backwards through time really underscores how a vestige of the nineteenth century still clung to the Jazz Age, how modernization still felt like a novelty, its shoots springing forth amidst a world still largely recognizable from the Victorian era. Then again, this may just be the subdued charm of Amsterdam shining through; we'll see if this impression lingers when we move back to Paris at the height of the Lost Generation.

The last silent film I watched for this series was The White Stadium, covering the Winter Olympics in St. Moritz from this same year. Full of innovative stylistic flourishes, it truly kept pace with the energy of late twenties cinema. Not so here, especially with the gargantuan record of The IX Olympiad in Amsterdam, emphasis on "record" as well as "gargantuan." Far more than any other Olympic documentary covered thus far, winter or summer, this film exists primarily to record these events as meticulously as possible over the space of four hours. Multiple qualifying rounds are pieced together and the filmmakers often follow a competition from beginning to end. In that sense, this plays more like a broadcast than a film setting out to shape what we see into a contained narrative. Not that IX Olympiad has no perspective; an Italian propaganda studio was commissioned by the Dutch committee and Italian athletes are highlighted throughout, often cheerfully giving the fascist salute. The effect is startling, often because they initially look like they're just waving and also because I recently watched the chilling 1936 Olympia, in which such salutes are ubiquitous and ominous. Here, pre-Nazi Germany, they appear more like a harmless national quirk, one more postwar eccentricity that the other countries are willing to tolerate...to an extent.

The Dutch film community was outraged that Italy had been given the assignment, and organized a counterproduction under the auspices of the German studio UFA. Much of the footage in this second documentary, The Olympic Games, Amsterdam 1928 is identical to IX Olympiad (in contrast to which, William Prager's cut runs a mere, sprightly three hours and twelve minutes). However, Amsterdam, 1928 is interspersed with Dutch titles and assembled with a bit more graceful aplomb. Most notably, it's actually the shorter film that makes room for a lengthy, lyrical marathon sequence against the picaresque backdrop of windmills, rowboats, and leafy parks, whereas IX Olympiad cuts immediately from the marathoners leaving the stadium to the victorious Bourghera El Ouafi (like Alain Mimoun, an Algerian running for France). Other notable athletes from the games, glimpsed in both films, include future Tarzan and current swimming superstar Johnny Weissmuller - who emanates pre-Hollywood charm after climbing from the pool - and Finnish middle-distance legend Paavo Nurmi, who finishes his Olympic career by grabbing a ninth gold medal in the 10,000m. I guess we'll be seeing more of him. Mikio Oda, meanwhile, becomes the first-ever Asian gold medalist by leaping 15.21 meters in the triple jump. In 1964, the Tokyo Olympic flag was raised to exactly that height in his honor.

On a personal note, I must confess that this was the point in the series where I most questioned my path. Seven hours of straightforward footage from sporting events a century past, with nearly half of the runtime just a repetition of the other?! If I'd watched the summer films in reverse order, this one might have killed the project but as I was nearing the end, I stuck to my completist impulse and bravely carried on. Some events held up better than others in this format. As noted, the marathon was a treat and equestrians held my interest. The team gymnastic exercises could be mesmerizing, but some of the swimming events were indecipherable despite the generally fine picture quality (at one point, spectators stand right in front of the camera and applaud as the race ends). And, to my surprise, the boxing matches felt entirely unengaging. Eventually I realized that since there was no period score, just a pleasant but repetitive modern piano accompaniment with occasional cheers mixed in, I might as well listen to something else: the latter four and a half hours of viewing were accompanied by podcasts on a variety of subjects. Perhaps this is the viewing equivalent of doping; if so, apologies to the purists.

Bud Greenspan Presents Vancouver 2010: Stories of Olympic Glory, prod. Bud Greenspan & Nancy Beffa

Winter 2010 - Vancouver, British Columbia (Canada)

After twenty-six years and ten films for ten games (seven of them in the winter, including the last six in a row), the eighty-four-year-old Olympic filmmaker Bud Greenspan passed away at the end of 2010. His last documentary was, it appears, largely produced without his usual supervision since he has no directing credit and was suffering from Parkinson's disease throughout its creation. IMDb lists longtime collaborator Nancy Beffa as the director but presumably out of respect, Vancouver 2010 lists her and Greenspan as producers and ignores the role of director. However hands-off he was on the project, it certainly bears his imprint, following the tried-and-true format he established in the early eighties: an anthology of individual stories of triumph and disappointment. Unlike his purely uplifting 2006 venture, this one does make room for failure, returning to the high-and-low structure of Greenspan's earlier work. That said, the film's uplifting or downbeat qualities depend less on how the subjects place in competition, and more on whether they achieve their personal goals. For example, the story of silver medalist Jennifer Heil, a defending champion who loses despite home turf advantage in moguls, emphasizes the agony of defeat while cross-country sprinter Petra Majdic's bronze is treated as a victory, albeit one no less agonizing.

In fact, Majdic's tribulation is so brutal that we have to wonder if the filmmakers envisioned it as a larger-than-life reflection of Greenspan's own struggle to continue his Olympic career amidst debilitating ailment. Onscreen, we see Majdic, a Slovenian trying to win her country's first winter medal, warming up just a few minutes before her race. She falls into a crevice on the side of the course which is so jarringly out of place that it reminded me of an Acme gag pulled from thin air in a Looney Tunes cartoon. Refusing to get proper medical attention, aside from a disconcerting X-ray in between qualifying rounds, she carries on with three sprints in a row: the quarterfinal, semifinal, and final, collapsing on the ground after each. When she's finally whisked off to the emergency room, doctors discover not just five broken ribs but a collapsed lung, pierced by one of the ribs when she refused to leave the course. Forbidden from attending the medal ceremony, she shows up anyway, hobbling to the platform with a tube in her chest. The episode is as riveting as it is grueling, with cameras capturing every step of the drama including the original accident, and interviews with Majdic placing us inside her head - as if watching her howl in pain during the race footage isn't suggestive enough!

Indeed, if I have a criticism of the material, it's that parts of the interviews appear redundant as athletes narrate incidents we're already watching with our own eyes. I don't recall this sensation with previous Greenspan docs, so perhaps this aspect is partly due to his absence but it's a minor qualm. These narratives are some of the strongest any Olympic documentary has offered and they are handled with passion and sensitivity. Vancouver 2010 also continues the trend in his later work of looking back on previous Olympics, often including his own footage. The best example of this features Clara Hughes, a Canadian speedskater who was inspired to turn her wayward teen life around after watching Gaetan Boucher's heartfelt race in the late eighties (remember those devastated parents in Greenspan's first winter film?). But the '10 documentary not only includes footage from her inspiration in Calgary '88 and her own bronze and gold performances in Salt Lake City '02 and Turin '06, it also includes her summer bronze medal in Atlanta '96 in video footage that was definitely used in Greenspan's documentary of those games. Hughes, it turns out, was once an Olympic cyclist as well as a speedskater, and what's more she's an active participant in the Right to Play charity that featured so prominently in the Turin '06 documentary, founded by Johan Olav Koss, whom Greenspan highlighted in Lillehammer '94. Thus this entire sequence feels like a visual/narrative survey of Greenspan's own work as well as Hughes', a fitting valedictory for both.

I also enjoyed the documentary's efforts to provide history lessons about the sports themselves. Only now, however many dozens of movies into the series, do I fully get the distinction between Nordic and Alpine skiing (the first encompasses both ski jumping and cross-country, while the latter - only popularized with the introduction of mechanized ski lifts - refers to downhill, initially dismissed as a leisurely pastime for dilettantes). And the final full sequence kicks off by waxing poetic about the glory of hockey as the Canadian gift to sporting, outlining its formation while quoting from - and interviewing - Roch Carrier, who wrote The Hockey Sweater. This is all to set up the film's climax, Canada's sudden death overtime victory against the United States, a rematch of the Canadians' half-century drought-ending gold medal victory in 2002 but this time with even higher stakes on the soil of Vancouver. Indeed, I've already mentioned the previous hockey tournament's staggering audience numbers, but the narrator of Vancouver 2010 informs us that this game received even higher ratings: an estimated 80% of the Canadian population tuned in. Even more than usual, this movie emphasizes the host nation's hunt for podium glory (it did not win gold either of the past two times it hosted the games, in Montreal for the summer of '76 and Calgary in winter '88).

After an unusual introductory montage teasing the upcoming stories, the film tells the following tales: aforementioned veteran Heil's defeat by American freestyle up-and-comer Hannah Kearney; Chinese coach (and former disappointed Olympian) Bao Lin's three figure skating pairs, one of whom - professional partners-turned-spouses Shen Xue and Zhao Hongbo - finally snatches the gold from Soviet/Russian dominance after a staggering twelve-Olympic streak (forty-six years!); Hughes' unexpected speedskating bronze medal in her last race; the American team's multiple-medal breakthrough in Nordic combined, one of only two winter competitions that the U.S. had never medaled in; Majdic's awe-inspiring cross-country endurance test; and of course, Canada's hockey euphoria. I notice that all but two of these have already been mentioned in this piece, a testament to the documentary's stellar selection of material, much of which demanded a deeper discussion than usual. The production team's attention certainly isn't on who generated the most headlines. Ski sensation Bode Miller, winning his first gold in his fourth Olympics (he has just one more in him), is ignored yet again. And, as in Turin, snowboarding superstar Shaun White is neglected along with the entire snowboarding discipline, aside from some demonstrations in the opening ceremony.

As with Turin, my memories of this Olympics are vague and more to do with where I was living at the time than the events themselves. I recall several late nights during a deep Massachusetts winter, bundled up on a fold-out couch in my apartment's living room (I'm not sure why, though it may have had something to do with which rooms were best heated), falling asleep while watching the bobsled and luge. My overwhelming impression is of low-key excitement and soothing comfort - at once both relaxing and stimulating, like a mug of mulled cider.

The Olympic Games as They Were Practiced in Ancient Greece, dir. Jean de Rovera

The Olympic Games in Paris 1924, dir. Jean de Rovera

Summer 1924 - Paris, France

The director of the first Winter Olympics film returned for the Summer Olympics later that year (both were held in the same country, as were all games until after World War II - including those scheduled for '40 and '44 - aside from the Amsterdam/St. Moritz split in '28). Up above in this round-up, I wondered if the busier Paris location and innovative, impressionistic nature of French silent filmmaking would give this documentary a different feel from the Amsterdam one but no, it generally feels of a piece with - and runs nearly as long as - the three-hour Amsterdam 1928 (if not quite as lethargic as the four-hour Italian cut). This earlier era of Summer Olympics filmmaking really brings Leni Riefenstahl's thirties breakthroughs into relief; none of the '24 or '28 films aside from the St. Moritz winter one are interested in painting a larger picture of the place, its residents, the athletes, or their sports. The closest we get to the competitors are those series of static, formal medium shot portraits in which they face the camera following a title card with their name, nation, and achievement. The films do sometimes find interesting - if not exactly startling - angles on the action, but if I'm not mistaken the primary purpose of this Olympic footage was to be chopped up into serialized presentations provided like TV broadcast highlights to theatrical audiences of the time. My viewing of them in this way is obviously an anomaly (at least in terms of intention).

De Rovera's 1924 output does include one more offbeat curiosity, the eight-minute The Olympic Games as They Were Practiced in Ancient Greece, which captures models on a dark stage re-enacting exactly what the title suggests, clad only in speedos and occasionally plumed helmets. At times they are frozen in individual poses, segmented phases of the proper procedure for a javelin throw or footrace, at others one performer (or two, in the case of wrestling) goes through the entire process himself. Much of this is photographed in slow motion - as is much of The Olympic Games in Paris 1924, for that matter. This is one of the few ways in which strict reportage is subdued for aesthetic effect, although of course the drawn-out action serves an analytical purpose as well: allowing the spectator to better appreciate the economy and force of movement. As is so often the case, Paris 1924 reserves most of its early reels for track and field, highlighting Paavo Nurmi and his rival (in '28 as well) Ville Ritola, and also the British sprinters Harold Abraham and Eric Liddell, later immortalized in the 1981 period drama Chariots of Fire - maybe the most popular Olympic film of all time (whose theme rivals Leo Arnaud's "Bugler's Dream" as the most popular Olympic music of all time - take your pick if you prefer the grandeur of John Williams' amplification). Other events include a cross-country race (won by Nurmi), which I initially mistook for the marathon, held on the rustic outskirts of the city. In addition to this event and the marathon, the film's later reels travel further afield for swimming, fencing, sailing, and so forth. There is no closing ceremony, and the ending of the movie could seem a bit perfunctory especially after all those hours. However, the image of two boxers joining in a friendly embrace, moments after they've finished battering one another, does speak to a broader theme of the games, and by extension this document of them.

One striking feature of these early century Olympic films is their attention to group gymnastic exercises (I can't figure out if these were competitive events or merely demonstrations), in which dozens of teammates synchronized their movements in an open field. This mesmerizing practice reaches its apotheosis in Riefenstahl's work, where it evokes a larger collective fascination that seized both the left and right in the thirties, but it's almost entirely absent from the postwar documentaries. On the other hand, there's no sign of an event which makes its mark on many mid-century documentaries: race-walking, with its contorted expressions and eccentric postures (the competitor must never let both feet leave the ground, which leads to some humorous images). Neither the team exercises nor individual race-walkers are shown at all in later films. Why do certain features of these sprawling Olympics gain and lose traction over the years, at least in terms of cinematic representation? Is it down to coincidence, the influence of the documentaries on one another, or larger trends of public interest? Paris 1924 also dwells extensively on action-oriented team sports like polo, rugby, and soccer (sorry, I mean football!), stretching out many plays with slow motion and letting the sequences run for many minutes, no doubt to a contemporaneous audience's delight. Tennis also shows up for one of the only times I can remember in any summer film - I recall a second or two featuring one of the Williams sisters in Greenspan's 2000 documentary and that's about it.

With only one more proper summer film to go, I wonder which events - besides the obvious track and field highlights - will attract a feature/serial filmmaker's attention. But before we reach that documentary, or the penultimate winter film, we'll take a peek at some shorter newsreels to commemorate the return of the Olympics after World War I.

+ bonus on summer 1920 newsreels from Antwerp, Belgium - no film produced

Some of the most arresting images from the Antwerp games aren't even from the games themselves. A Pathe newsreel opens with footage of the Princess Matoika, a German transport ship which had been commandeered by the U.S. Navy three years earlier. Its deck has been transformed into an almost comically crowded training quarters, with boxers sparring, rowers rowing in place, and runners jogging around the perimeter. A salt water swimming pool is even constructed on the deck, while javelins and discuses are tied to the ship so they won't be lost when tossed out to sea. The whole set-up looks like a jolly lark in this clip, but the American team was quite miserable with these conditions as well as their generally tight and uncomfortable quarters. They submitted complaints to their national Olympic committee before landing, an incident that was later memorialized as "the Mutiny of the Matoika". A similar spirit of grueling physical hardship and beleaguered post-war (and post-pandemic!) malaise characterized much of this Olympiad, held in Belgium in honor of that country's place in the previous conflict. Many governments grumbled about sending delegations - an idealistic, peaceful gathering of nations seemed absurd in this moment - and the previous summer had been reserved for the Inter-Allied Games, in which only the victorious belligerents were allowed to participate (Antwerp's official Olympiad expanded the field to include nations neutral in the war but excluded the defeated Central Powers). The IOC and the Belgians pulled the event off despite these hindrances, and so the tradition continued, and grew; indeed, Antwerp was the first time the Olympic flag was unfurled.

Interestingly, as the last Summer Olympics held without an official winter companion (although unofficial international competitions had been staged for several decades), the 1920 games actually incorporated a week of "winter in summer" sports including hockey and figure skating. From that humble beginning, let's jump forward to the lumbering behemoth that Winter Olympics would become ninety-four years later...

Rings of the World, dir. Sergey Miroshnichenko

Winter 2014 - Sochi, Russia

The first post-Greenspan Winter Olympics film marks a jarring departure from his formula, or indeed that of any other Olympic filmmaker. That's less because Rings of the World abandons its antecedents than because it synthesizes several components of them. The visual style feels closest to the dramatic experimentation and extreme point of view shots popular in the seventies winter documentaries while the adrenalized editing rhythms (and wall-to-wall music) echo the early eighties winter documentaries. Like those 1980 and 1984 pre-Greenspan films, this has a bit of a "big-budget TV commercial" feel to it although in this case Miroshnichenko is not advertising a product or even the games themselves, so much as the host nation. Without leaning too heavily into the "Putin is Hitler" comparisons that all too many contemporary commentators are so fond of, no Olympic film has featured a head of state this prominently or frequently since Leni Riefenstahl's 1936 Olympia (although Prince Philip is ubiquitous in the fifties Melbourne films). This may also be as flamboyant and stylized as Riefenstahl's work. The opening sequence features a muscular model in a sleek, skintight suit dissolving each credit with her winter breath, a combination of Olympia's brooding prologue and a James Bond introduction. Long gone is Greenspan's make-do reliance on lo-fi race footage and brightly lit talking heads. Rings of the World has that unusual, archetypally Soviet flavor of monumentalism and kineticism. Its best moments crackle with the energy of Eisenstein; the pounding, dissonant score is certainly going for a Prokofiev effect although the film does sometimes lapse into being a heavyhanded, and rather exhausting, three-hour music video (take, for example, the quick cuts back and forth to a coach yelling in time to the throbbing soundtrack).

With Greenspan gone, this film lacks the familiar focus on biographical build-up, but the American documentarian's imprint can still be felt in the way Miroshnichenko relies so heavily on the voices of the athletes themselves to guide the movie. Indeed, there is no narration aside from these chopped-up interviews - similar to Caroline Rowland's First from two years earlier. The participants tend to reflect upon the sports themselves rather than detail their own personal trials and tribulations leading up to the competition (although there is a bit of that too, especially when figure skater Evgeni Plushenko leaves the ice following one too many injuries, never to return). They are also prompted to discuss gender quite a bit, with some scoffing at the notion of direct male vs. female competition while others muse that it could and should be possible. Perhaps the most Greenspan-esque passage of the movie is its focus on the American and Canadian hockey coaches, of both men's and women's teams: we hear them muse about their focus and the mercurial shifts within a game, and watch as these phenomena take their toll in real time. Also dramatically potent is the showdown between the Russian-born Swiss snowboarder Iouri Podladtchikov and, finally, Shaun White in one of his rare halfpipe misses - a sequence which incorporates a striking collage of snowboarders floating midair simultaneously, echoing a similar superimposition during the ski jump sequence. Such dual portrait of respectful rivals were a Greenspan trademark going back to his blow-by-blow of the 1984 decathlon.

Aside from those other cinematic comparisons, the film (and Olympics) that Rings of the World most consciously evokes is O Sport, You are Peace!, which covered Moscow in the summer of 1980. One of the 2014 mascots, a giant bear, even cries in its final moments (along with many of the spectators), just like good old Misha. Like those games, the most boycotted in history, this Winter Olympics would also fall under a heavy cloud albeit one whose greatest impact was felt after, rather than during the event. In this case, a massive doping scandal led to the retroactive disqualification of many medalists and a humiliating penalty that lasts to the present day: the proud host of 2014 can no longer compete under its national flag or name, relegated to a delegation of officially approved-but-unaffiliated athletes on the neutered "Russian Olympic Committee". Interestingly, the film includes a passage in which the interviewees all condemn the use of performance-enhancing drugs (for what it's worth, none of them would be among the disqualified). Even in the lead-up to Sochi, there was a lot of negative press expressing concern with the IOC's decision to go forward, with great emphasis on Putin's authoritarianism and persecution of homosexuality; there may have been some projection/deflection going on, as the U.S.'s own conversion to the pro-gay marriage position was less than a year old at this point. Corruption tied directly to the Olympics itself also received extensive coverage, with oligarchs pocketing huge sums in a flurry of construction and promotion. This quickly ballooned into the most expensive Olympics in winter or summer history.

I remember watching, with a co-worker, a VICE News program investigating this particular issue, and then returning a few weeks later to this close-quartered, attached bungalow apartment in Hollywood to watch the closing ceremony. We were impressed by the spectacle, however troubling the underpinnings; I can also recall watching the opening ceremony (probably in my own Pasadena home) because the giant, floating hammer and sickle representing the communist period of the country's history left a vivid impression. Looking back on those Californian evenings, I realize this must be the only winter games I watched in a warm climate. As with the previous two winter games, my picture of this particular broadcast is tightly wrapped around where I lived and worked at this particular time, with both global controversies and personal viewing habits part of my larger mosaic of Olympic memories. Regular readers of this site may also find it interesting that the Sochi games ended just a handful of days before my still-ongoing Twin Peaks focus began; in fact, the ceremony aired on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the night Laura Palmer was murdered. More pertinent to the games themselves, the last five days of the Olympics coincided with the anti-Russian Maidan revolution in Ukraine, whose aftereffects we are very much still dealing with right now. And I do mean literally right now. We've reached a point in our march forward through Winter Olympic history in which the tendrils of the past are beginning to touch the present.

The Games of the V Olympiad Stockholm, 1912, dir. Adrian Wood in 2017

Summer 1912 - Stockholm, Sweden

Although this round-up has a few more rounds to go, this is the final film I'll be discussing from the Criterion Collection's 100 Years of Olympic Films boxset. It's both the earliest and, in a sense, the last of those documentaries. Shot a couple years before World War I a few months after the sinking of the Titanic, this footage is obviously older than anything else in the series, but it was re-discovered in the twenty-first century and edited by Chris Rodmell under the supervision of director Adrian Wood and the IOC record-keepers (who assembled the events chronologically). No one onscreen was alive when The Games of the V Olympiad Stockholm, 1912 got its proper release and no one who worked on that release was alive when the games themselves took place. As a documentary whose own creation spans a century, this film provides a proper endpoint for our summer survey. Perhaps because the footage was assembled with a modern audience in mind, or else simply because of the novelty of its place so early in cinematic history, I found this to be the most compelling of the three silent Summer Olympics. Peter Cowie's accompanying essay - the first in the companion book and the last I read - captures the magic of this glimpse into a long-ago past, "the immediate intimacy of so many of its shots, as athletes, posing after a victory, stare into the camera as though reaching out across the years to a future audience; some smile, some gaze sternly, others scowl brashly." In his conclusion to the book, Cowie describes this collection as "a panoramic vision of life across the decades, on and off the field, commencing with the belle époque elegance of Stockholm in 1912 and concluding with the multicultural jamboree of London in 1912."

It's a treat to see the grand, stately brick stadium a second time, since it also featured in the 1956 equestrian documentary (when those events were held away from the rest of the Melbourne Olympics due to quarantine rules). This location contributes to a broader "old-fashioned" aura alongside other elements: the highly formal fashion, the women's massive hats, the horse-drawn carriages with hardly an automobile in sight unloading aged royals who must have been born deep into the nineteenth century. Indeed, even the spry youngsters onscreen hail from the 1800s - unless one of the pint-size coxswains in a rowing contest was twelve or under. On the other hand, there's a certain breezy freshness to the film, similar to what I detected in the 1928 doc but even more so here. The effect Cowie describes is profound: the swimmers who giggle and hide from the camera's unblinking gaze behind towels; the cheerful marchers and spectators in an extended street parade that consumes one of the movie's most irrelevant yet absorbing passages; the kid in what looks like a boy scout uniform who playfully jostles Duke Kahanamoku (the legendary Hawaiian who went on to popularize surfing) on his way out of the pool, reminding him to look at the camera. All have the casual, unpresuming air of people going about their everyday lives without announcing that they live in a distinct historical era, yet all belong firmly to yesteryear (a quaint phrase itself, suggestive of a time when the old or even middle-aged could sigh nostalgically with warm, firsthand reminiscences of this period - when it was out of reach but not out of mind).

There are darker moments too, treated in the same laid-back, straightforward manner as the victors' joy: one title informs us that the exhausted man we're about to see, sipping water at a rest stop in the marathon, will soon be dead. Francisco Lazaro, the Portuguese standardbearer, had waxed himself head to toe with animal fat to remain fleet and free of sunburn, but instead he restricted his own perspiration; reportedly, he told someone before the race, "Either I win or I die" (the only source on this cites "the story goes..." so take that as you will). Does this man's acute proximity to his own mortality have any particular significance when everyone in the movie is, to use Barry Lyndon's turn of phrase, equal to him now? It feels different, but this is one of those mysteries that the Olympics - a recurring testament to the momentary solidity of quicksilver youth and vigor - can only provoke rather than answer. This comes to mind when we glimpse - only in an awards ceremony, alas - the original "All-American": decathlon/classic pentathlon gold medalist Jim Thorpe, whose medals were soon stripped because he'd briefly played baseball for pay as a youth (his standing was posthumously restored in the eighties). Even in death, Thorpe was haunted by the conflict between financial need and a dignified legacy. His widow shipped his remains to a random town in Pennsylvania which, looking to attract tourist attention, built him a monument and renamed itself in his honor. The rest of his family has fought ever since, in vain, to bury him on Native American land. Another soaring Olympian yanked down to earth. To quote the great final line of Patton, "All glory is fleeting." Incidentally, that future World War II general was himself at these very games, and in this film, fencing in the modern pentathlon.

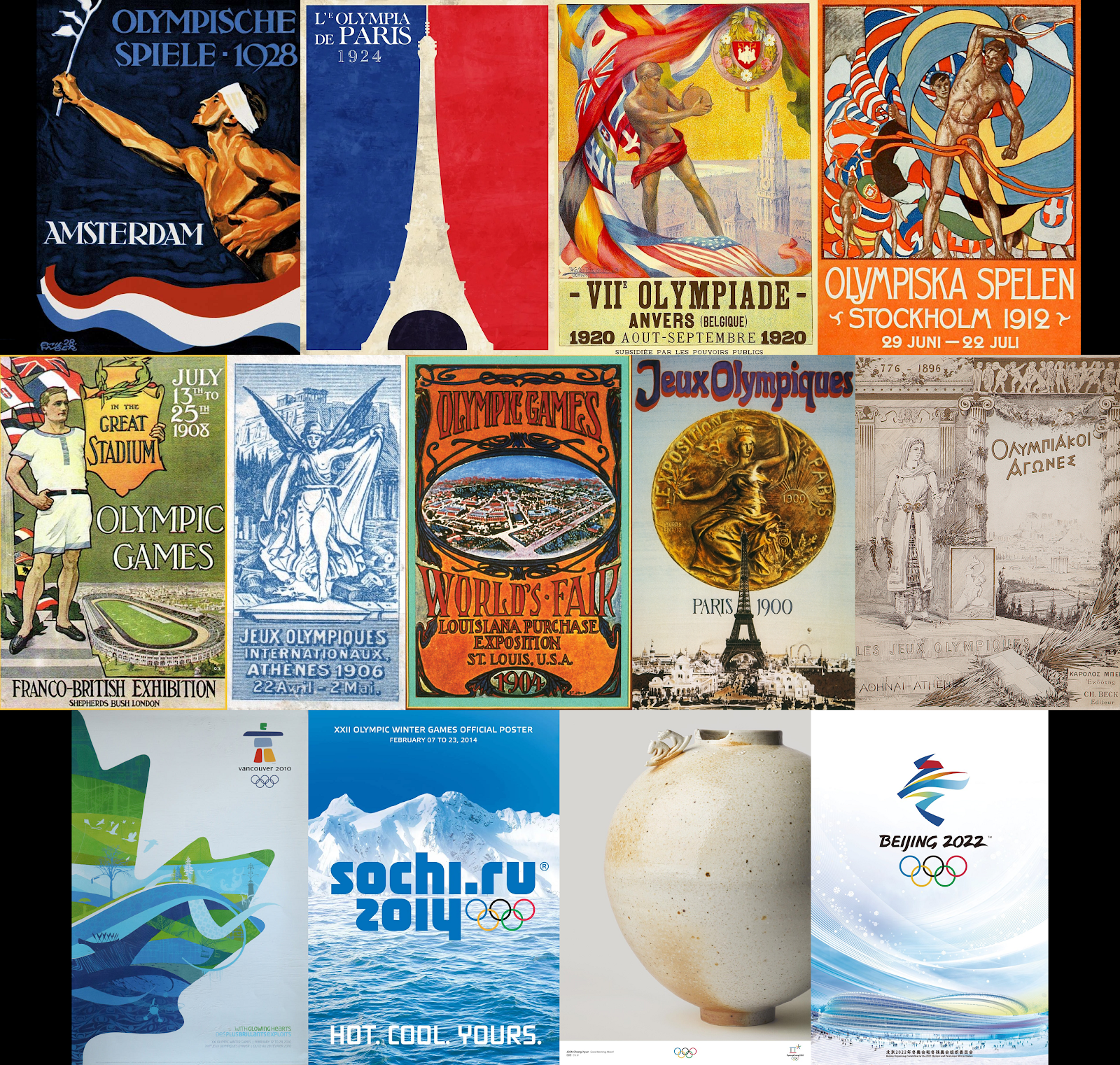

Let's end this reflection with a tribute to the way that celluloid (and, eventually, digital) can capture, extend, and suspend that brief moment of glory, mixing it with others across eras and around the globe, woven together to transcend the limits of space and time. Here is the vivid montage compiled as an official teaser by Criterion:

Now it's on to three more stops: the distant past, the immediate past, and the present. We'll conclude as we began, beyond Criterion's parameters.

+ bonus on summer 1908 newsreels from London, England (UK); 1906 newsreel from unofficial "Intercalated Games" from Athens, Greece; 1904 newsreel from St. Louis, Missouri (USA); 1900 newsreel/photos from Paris, France; 1896 photos from Athens, Greece - no films produced

In the twenties and thirties, available films are interspersed with Olympics only covered by newsreel. Now, beyond even the earliest feature, newsreels give way to no film record whatsoever (I could only find crowd footage from Paris, while videos with images from the very first Olympiad are limited to montages of still photography). The 1908 Olympics is first on the docket and arguably the most important, probably the most noteworthy, and certainly the most well-documented of the five remaining summer events. I watched several of these records, with a fair amount of overlap, on YouTube and felt I was traveling even beyond the sensation provided by Stockholm, 1912 into a past so remote, and a filmmaking approach so rudimentary, that there wasn't anything left to be wistful about; the last chain of connection to the present had been broken. Which isn't to say these events were uninteresting on a human level; however, this dramatic quality tends to be captured more by later re-tellings than the fragments available from the time. The piece of film that speaks the loudest on its own - a bustling crowd of officials and policemen hurriedly accompanying a slight Italian man across the marathon finish line - is even more absorbing when you learn the context from a book or, as I did, this BBC documentary about the London games.

Dorando Pietri was a baker who took up running spontaneously when a footrace passed by his workplace one day (as the legend would have it). In London, he found himself at the front of the marathon in the final stretch but collapsed multiple times on the track. Disqualified because the surrounding crowd practically carried him into first place, he was nonetheless considered a hero for his effort. Much intrigue swirled around this controversy with some alleging that officials had been desperate to give the gold to a non-American (given that Johnny Hayes was close on Pietri's heels) while others claimed that Irish judges were actually trying to interfere and get Pietri disqualified in favor of the Irish-American Hayes. The rivalry between the U.S. and Britain was intense, with James E. Sullivan, head of the American delegation, eagerly feeding the press anecdotes of the hosts' perfidy (never mind that Sullivan himself had an odious legacy connected to the 1904 games, which we'll get to in a moment). Next to the marathon, the greatest tumult occurred in the 400m when judges snipped the tape before the race was over and kicked out an American who allegedly hit the Brit trying to pass him. The other two Americans refused to run again, leaving a single man to run by himself and collect the gold. None of this was in keeping with Baron de Coubertin's lofty ideals of international brotherhood through sport, but the turmoil generated a great deal of public interest and made 1908 the year that the Olympic Games finally solidified themselves as an institution. This tension between the utopian dream of the Olympic movement and the eye-catching drama of national rivalry and interpersonal conflict remains quite relevant up to and very much including 2022.

Moving back from that moment of consolidation - the first Olympics in which teams entered under their own national flag instead of individuals forming an athletic melting pot - the early history of the games is littered with embarrassment, obscurity, and notoriety. In 1906, the tenth anniversary of the modern Olympics, there were "Intercalated Games" in Athens with the intention that the original Olympic homeland would host such events halfway between the Olympics in other countries (however, this would be the first and last such event and the IOC retroactively stripped 1906 of its official status). These newsreels, often mislabeled as "1896", show Greek and British royalty gathering inside the stadium to watch a "standing high jump" in which - many, many decades before the Fosbury flop - competitors rigidly leap straight up and down over the bar. St. Louis 1904 rivals London 1908 for the most drama, mostly because of an astonishing marathon in which the hallucinating, deathly sick Thomas Hicks arrived at the finish line having consumed raw eggs, several flasks of brandy, and literal rat poison - and he only got the gold when it was discovered that the man who finished first had cheated by hitching a car ride for part of the race. Of course, none of this is present in the few celluloid fragments I found online; for the details of that incredible story, and much, much, much more, I beg you to watch this incredible twenty-minute video about one of the most extraordinary incidents in Olympic history. It's equal parts horrifying, darkly hilarious, and poignant...well, maybe mostly horrifying. The aforementioned 1908 delegation head Sullivan, who organized the 1904 games alongside a racist "human zoo," ensured that there would be almost no water stations along the marathon route so that he could observe the effect of dehydration upon the runners, a ghoulish scientific experiment.

Both St. Louis 1904 and Paris 1900 were completely overwhelmed by their attachment to international expositions surrounding them. Both Olympics stretched for months on end, in Paris' case often coterminous with and indistinguishable from non-Olympic sporting events. Indeed some of the "gold medalists" (a distinction not actually introduced until St. Louis) had no idea they were even officially considered Olympians when they entered and won their competitions. This leaves us finally with Athens 1896, which appears like a breath of fresh air amidst these sordid catastrophes - the idyllic origin story of the modern games. While researching, I sampled parts of an eighties miniseries which romanticizes and mythologizes the first Olympiad, centering in particular the Greek shepherd and soldier Spyridon Louis who won the marathon to unanimous delight. Louis' national roots, his noble ideals, and his quintessentially amateur status endeared him to the crowd, launching the modern games on an appropriately poetic note. Unfortunately, his final Olympic appearance was in 1936, forty years to the day after his marathon victory, leading the Greek national delegation and offering Adolf Hitler a literal olive branch from Mt. Olympus as a gesture of peace. Several years later, Louis would die on the eve of the fascist invasion of his beloved homeland.

My months-long audiovisual experience of the Summer Olympics ended with a few final videos, frozen, pixelated images set to techno music with colorful titles and 3D transitions imposed over them - the closest I could get to this long-ago event. And so the mists of time enclose and envelop one of my two directions, the one which began in the warm weather of Tokyo seven months ago. Now we can only move forward to our wintry conclusion, with one more stop along our path to the present.

Crossing Beyond, dir. Seung-jun Yi

Winter 2018 - PyeongChang, South Korea

Perhaps inspired by the five Olympic rings, Crossing Beyond focuses on five teams or individuals in five different sports - with five very different outcomes but a similarly optimistic takeaway. Although Bud Greenspan's influence can still be felt, Yi's aesthetic is closer to Caroline Rowland's First from London 2012. They also share an impressionistic documentary style and immersion in the subjects' points of view, perhaps reflective of larger aesthetic trends. The profiles and competitions are cross-cut (rather than isolated into distinct standalones episodes within an anthology), although much more time is spent building these competitors up than watching them actually compete in the second South Korean Olympics; the opening ceremony does not appear until about halfway into the documentary (and it samples that familiar "Hand in Hand" theme song from the first South Korean Olympics). The Afghan alpine skiers Sayed-Ali-Shah Farhang and Sajjad Husaini are shown practicing in their war-torn homeland, where the few interested locals resort to thick, rough-hewn wooden skis and poles, hoping to merely make it down the mountain standing up. Seeking world-class training in St. Moritz, these two initially skied alongside more experienced children, developing skills at the slalom that gave them a real shot at an Olympic presence if not an Olympic podium. Akwasi Frimpong also found himself out-of-place in winter sports, with an experience that spans both disciplines and cultures. Born in Ghana, raised as an undocumented immigrant in the Netherlands, schooled in Utah where he now raises a family, Frimpong found success as a hardworking vacuum salesman (we follow him door to door in one of the more unexpected passages in any Olympic film). But he couldn't shake his athletic dreams and used this day job to fund his passionate pursuit first as a Dutch sprinter and then, after a devastating injury, as the first African to compete in the skeleton.

Also struggling with a sense of displacement and belonging is Park Yoon-jung (otherwise known as Marissa Brandt). A Korean-American adopted into a white family as an infant, she spent years avoiding her heritage, only to embrace it when invited to participate on the South Korean hockey team. In a remarkable story that isn't really the film's focus - you could even miss it while watching - Park's sister Hannah Brandt was also in PyeongChang, competing for the gold-winning Americans. While Park's team did not achieve the same glory, they found themselves in an even bigger spotlight...arguably the biggest of the entire games. With just weeks to go, Park and her colleagues were joined by North Korean athletes to form the only unified Korean team of this or any other Olympics. In what may be the film's dramatic centerpoint - where its personal stories coincide with the grander tale of the 2018 Olympics and, indeed, world history - we watch the North and South Koreans awkwardly meet, train, and grow to respect and enjoy one another's company until, at Crossing Beyond's conclusion, they tearfully part ways and promise to meet again, even though they know the odds are stacked against that. The other two profiles are, by contrast, quieter and more personal. Unlike the other three stories, they feature athletes who arrived in PyeongChang with great expectations. The Austrian Daniela Iraschko-Stolz was a previous silver medalist in the ski jump, a participant in the first-ever women's competition for that sport in 2014 who hoped to repeat or even better her achievement four years later. First-time Olympian Billy Morgan was a British skater-turned-snowboarder who (like Farhang, Husaini, Frimpong, and arguably even Park) had trouble training in his home environment.

When we finally reach the conclusions of these separate narratives, many feel - quite purposefully - anticlimactic. Indeed, the Afghans never even got to PyeongChang at all, failing to qualify at a crucial preliminary trial. The film also shows Iraschko-Stolz coming in a disappointing sixth place, falling just short of the hundred meter mark she'd reached in the past. Frimpong, perhaps unsurprisingly given how new he is to the sport and how limited his training options have been, came in a distant thirtieth out of thirty on the sliding track, while the Korean hockey team barely managed to score a couple goals in their three losses before getting eliminated. That said, one of those goals, thanks to an assist from Park, earns a celebratory presentation worthy of Greenspan - as does Frimpong's triumphant, crowd-pleasing dance after landing in last place: he got to be there, and that's all that counts. In an interview near the jump, Iraschko-Stolz observes that if only the relative handful of medalists, among the thousands of competitors, could consider themselves satisfied then the Olympics wouldn't be worthwhile, would they? Of the five, only Morgan ended up on a PyeongChang podium; following some hair-rising big air runs, he landed his signature "quad cork" and earned a bronze medal. The emphasis here is clearly on the preparation, the camaraderie, the personal discipline, the dream - not the victory or loss.

Since 2018, most of these competitors have moved on. Park was not on the 2021 South Korean hockey roster, not that it mattered - after years of decimation from Covid restrictions, lack of public interest, and attrition from "imports" returning to the U.S. (perhaps Park was among these), the women's team was unceremoniously shut out during the qualifying rounds long before Beijing. Frimpong, who had qualified in 2018 due to a continental quota, was unable to compete in 2022 due to a rule change, despite his protests. Most tragically of all, but in keeping with this general theme of how much has changed since just a few years ago, Farhang and Husaini were forced to flee Afghanistan during the U.S. withdrawal, collapse of Kabul, and Taliban takeover last summer. They've re-located to Italy and are uncertain about their future in the sport. Already they'd been having trouble properly training for competition in 2022 and were unable to attend the games even in a representative or observational role, as originally planned, due to passport issues. Morgan decided to retire on top (or near it) a couple years ago, while Iraschko-Stoltz was the only one of these six to appear in Beijing. However, in one of many scandals of these games, she and several others were disqualified prior to jumping because their outfits were considered too loose in an advantageous way. North Korea, meanwhile, whose last-minute reconciliation with the South was such an enormous story in 2018, was barred by the IOC in a convoluted response to their own Covid-inspired boycott of Tokyo. Almost everything we see in this film, the most recent piece of Olympic cinema available to us, already belongs to the past.

For me personally, this trip back to PyeongChang also represents a moment to come full circle and make contact with the present. In 2018, I lived in the same place and did the same work I do now - if other Olympic films have reminded me of what I've left behind, this one underscores my current conditions. These games were also the only ones I ever discussed as part of my Lost in the Movies online work, in this case for my then-brand-new Patreon podcast; I spent several minutes musing on the appeal of the Winter Olympics generally, reflecting on the Korean peace moves, and recommending relevant podcasts. A month afterwards on a family visit, I'd watch Moon Jae-in and Kim Jong-un greet each other across the Korean border with my mother, my aunt, and her nine-year-old grandson - telling him that he was watching history unfold. Of course, it was hard to expect a deeper peace process to unfold beyond that gesture, and indeed it hasn't really (putting aside the high comedy of the Trump/Kim summit later that year - I'm thinking of the North and South rapprochement that Moon carefully arranged). Still, something about this particular Olympics caught a mood of idealistic coming-together which the Olympic movement always seeks, often evokes, and seldom truly achieves.

When I remember these games, they don't just evoke the heady, unnerving, and oddly hopeful political zeitgeist, so much of which seems to belong to an entirely different world. I also envision a parade of prominent American athletes never seen, or only momentarily glimpsed, in Crossing Beyond - skiers Lindsey Vonn (at the weary end of her career) and Mikaela Shiffrin (at its bright start), snowboarders Shaun White (staging a comeback after the disappointment in Sochi) and Chloe Kim (experiencing her star-making breakthrough) - all of whom would find their way to 2022 in a variety of roles: retired commentator offering advice to former teammates and rivals, tragic figure in the blinding spotlight, aging competitor making his last attempt, and champion solidifying her reputation. And of course, as with all the games I lived through, I marvel at the threads that connect me to that moment in my own life as well as those that have long since been cut. Therefore, I find myself experiencing both a poignant nostalgia for a particular era and a feeling that it doesn't quite belong to the past despite the intensity of the intervening period. February 2018 was also when I came up with this project, I think due to a particular podcast I listened to at the time, which introduced me to the Criterion series. I hoped to prepare this long beforehand (ha ha ha), and knew that it would stretch from the Tokyo games scheduled for the summer of 2020 (laugh or cry at that one too, take your pick) to the Beijing games scheduled for the winter of 2022. And indeed, the work took me right up to that limit.

As I write this, the TV is paused in the other room; NBC is about to run (or re-run, given the time difference) the final bobsled heat followed by skiing and skating events on its last night of live coverage. The disappointed Shiffrin has one more chance to get a medal, albeit as part of a team rather than individually, and hundreds of other moments and events lay waiting on demand depending how late I decide to stay up (all night?) before the opening ceremony runs live early Sunday morning. When I return tomorrow to compose the last entry of this last round-up, my reflections will follow a broadcast rather than a movie and the journey will officially be over. But tonight there's still more to explore. This is my last night of Olympics after months spent in this world, so I hope it's a long one.

(epilogue following Beijing, China - Winter 2022)

When this series began last summer with the Tokyo 2021 broadcast, my write-up was relatively short and only touched briefly on a handful of athletes or events. Not so with Beijing 2022; whether due to my own preference for the snow and ski sports over the warm weather alternatives, the fact that this entry follows months of concentrated Olympic coverage, or the actual nature of these games - which were rife with shock, controversy, and other forms of drama - it just feels like I have more to say about this than Tokyo. Let's start with the political/historical context that preceded this Olympics and haunted it throughout. As in 2008, Beijing's initial selection was controversial but as the games got closer the discontent only grew, climaxing with a U.S. diplomatic (but not athletic) boycott. The Americans cited both the repression of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang Province and, directly related to Chinese sports, a bizarre and convoluted episode involving tennis superstar Peng Shuai and her allegations of sexual misconduct and abuse of power by a prominent Chinese Communist Party official and Olympic organizer. The neverending Covid-19 pandemic also hung over the proceedings as in Japan, but China took a much stricter approach: a "closed loop" quarantine that isolated the competitors and severed all Olympic participants from the broader population.

Given this context - and caught in the perpetual tension between the U.S.'s capitalistic impulse to do business with huge markets and its hegemonic determination to outflank and overpower any rival superpowers - NBC struggled to both celebrate the Olympic spirit and reflect from a distance on this presentation as a piece of propaganda. As discussed in my review of Olympia from the previous round-up, this resulted in a disorienting voiceover during the opening ceremony: as a cheerful child chorus sang in front of giant snowflake, the announcers informed the audience about China's now-defunct "One Child" population control policies. Setting off on an awkward foot which would continue throughout the broadcast, these games received the lowest ratings of any Olympics in American TV history - probably due in large part to the larger shift in viewing habits during the pandemic. And they were full of disappointments for those Americans who did tune in. The biggest disappointment was the most hyped figure coming into Beijing: skier Mikaela Shiffrin, one of the premiere talents of PyeongChang who was scheduled to compete in six separate events and possibly medal in all of them. Instead, she medaled in none - and failed to even make it down the slalom course in her three strongest competitions. The image of her sitting forlornly on the side of the mountain, holding her helmet in disbelief, will remain one of the most iconic of this Olympics; a grim complement to the equally-hyped, equally-jittery Simon Biles' exit last summer. Shiffrin eventually came close to bronze with her teammates in the exciting mixed-team race on the last night of the Olympics, but she is now leaving Beijing empty-handed, something nobody expected.

There was a general sense in 2022, as there often is, of old stars falling as new ones rise. Shiffrin handled her humiliation with grace in post-run interviews, and she's only twenty-six, with plenty of time for a comeback. Still, it was hard not to remember her cheerful triumphs in 2018 when a wistful-looking teammate Lindsey Vonn, on the eve of retirement and having recently lost her beloved grandfather, struggled to pull of a bronze while the chipper young Shiffrin soared onto silver and gold. This time, it was Shiffrin's turn to appear world-weary. Coming immediately off a bout of Covid (and still grieving her father who died two years earlier, unrelated to the pandemic but at its outset), she faced the toughest athletic challenge of her career. The thirty-five-year-old Shaun White, meanwhile, said his farewell in the halfpipe, holding his own against much younger rivals (some of whom were literally infants when he revolutionized the sport at nineteen). When he fell on his last run, he doffed his helmet and rode off to the finish to respectful cheers: the end of an era. Other early millennials had more luck. Forty-one-year-old Frenchman Johann Clary became the oldest alpine medalist in history with an unexpected silver. Two other eighties babies, Lindsey Jacobellis and Nick Baumgartner, made history in the thrilling mixed-team snowboard cross race, my favorite memory from these games and one of the most exciting competitions I've ever watched (Jacobellis also won an individual cross event). And American bobsledders Elana Meyers Taylor and Kaillie Humphreys racked up medals - though they couldn't unseat the Germans - and captivated reporters with their unique stories; Taylor fought off Covid to become the most decorated black athlete in Olympic history while Humphreys left her Canadian team (citing harassment) to become an American citizen. This will probably be the last Olympics to feature my age bracket in any significant manner, so this felt like a fitting tribute.

Zoomers, of course, also left their mark. Alongside Shiffrin and White, NBC zoomed in (no pun intended) on returning early twentysomethings Chloe Kim and Nathan Chen; in 2018 the first exploded onto the snowboarding scene and the second stumbled and dashed his figure skating dreams. This time, both won gold. However, the real Beijing breakout was an eighteen-year-old freeskiing fashion model from San Francisco, who scored a 1580 on her SATs and is headed to Stanford this fall. A perfect success story for the American media, right? Well, not exactly. In fact Eileen Gu's triple-medal Olympics - two golds in big air and halfpipe and a silver in slopestyle - only underscored America's growing unease in a world that no longer seems under its sway. Wrapped in the red-and-yellow-starred colors of the People's Republic of China, Gu chose to compete for her mother's homeland, causing many Americans to look on with discomfort as the Chinese public embraced her wholeheartedly (unlike Zhu Yi, an American figure skater who went so far as to renounce her citizenship in order to compete for China but took a humiliating spill on the ice). Meanwhile, as Russian troops massed along the Ukrainian border and triggered an international crisis that ran through the entire games (and remains unsettled at the time of this writing) the officially nationless "Russian Olympic Committee" also caused quite a stir in Beijing, resulting in the biggest and most damaging story of the 2022 Winter Olympics.

Notorious figure skating coach Eteri Tutberidze (unlovingly dubbed "ramen sister" and "noodle hair" by Chinese social media for her distinctively wavy blonde locks) arrived in Beijing with the three strongest contenders in the women's team and singles event - and a reputation for horrific abuse from her Sambo 70 skating club in Moscow. Consisting of Anna Shcherbakova, Alexandra Trusova, and Kamila Valieva (two seventeen-year-olds and a fifteen-year-old), her team won the gold and seemed poised to sweep all of the top spots as individuals too. Astonishingly talented but also, in many observers' eyes, harsh and cold in their style, the teens delivered technically exacting performances as they landed quad after quad, their gloved hands swinging sharply to abrasive music choices (covers of Requiem for a Dream and Iggy Pop). Long gone was the sweetness of Sonja Henie or the spunk of Tara Lipinsky. Some defended this approach as a step forward for ladies' figure skating (comparing it to the routines expected of men) while others mourned the emphasis on precision rather than passion. And then the other skate dropped: Valieva had tested positive for a banned substance - she would be allowed to compete pending appeal but if she won any individual medal, there would be no ceremony for anyone. An outcry emerged; Lipinsky herself, co-hosting the program with the flamboyant former Olympian Johnny Weir, devoted much of their commentary to a scandal that shook their understanding of how the sport was supposed to work.

And then, the final event. Valieva, never one to stumble, fell numerous times in her performance - the more conspiratorial viewers wondered if she was put up to it, to ensure her teammates their public recognition. A shocked world watched as she collapsed into her coach's less-than-comforting arms, while Japanese skater Kaori Sakamoto wept with relief for her bronze, Trusova (furious that her record five quads and staggering technical score resulted only in a silver, rather than gold - and perhaps about other, unspoken, stresses and pressures as well) screamed in Russian at Eteri and initially refused to take the podium, and a dazed Scherbakova stood, masked, silent, and alone with nobody congratulating her for her gold. All was caught on camera in excruciating close-up as it unfolded, in one of the most bizarre and uncomfortable moments in broadcast sports history - closer at times to a dark reality show that a dignified contest. Will there be consequences for the adults who threw these children into such a cauldron? Even risk-averse IOC President Thomas Bach, perhaps trying to compensate for the fury he'd stoked by permitting Valieva's performance in the first place, condemned Eteri's response to her devastated pupil as "chilling." This is one of those moments that unfolds in real time but can only be more deeply understood afterwards - precisely where an Olympic documentary could potentially go further. For now, however, the story ends there.

With its full sweep behind us, the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing presents an appropriate endpoint with its world-historic context, thrilling and devastating victories and defeats, and dips into ongoing athletic sagas that unfold and overlap through several Olympics. Despite their many thrills and delights, these may be among the darker, more sobering games in history, something of a contrast to the hopefulness that shimmered briefly in PyeongChang. The Winter Olympics have now been tied to a long run of high-stakes host countries: Russia in 2014 on the eve of the Ukraine crisis, South Korea in 2018 in the midst of North/South reconciliation, and China in 2022 in the wake of Covid and human rights scandals - and amidst another Ukraine crisis, although perhaps Russia's Olympic-concluding hockey loss to Finland late last night presents a promising omen (update, a couple days later: it did not). By contrast, 2026 will be hosted in Italy in what promises - or hopes - to be a reprise of the warm, soothing Turin games twenty years earlier. At the Beijing closing ceremony, a theme of "Duality Together" played out over both specific and archetypal images of city and country, to honor the two hosts: Milan and Cortino d'Ampezzo (the latter for a second time, after the '56 event which inspired that dazzling color documentary I reviewed a few weeks ago). Depending how long the Olympics continue on from there, what I've explored in this series may only be half the story, or even less than that.

This story was, and is, one of cinema as well as sport but most of all it's a story of human experience, both the extraordinary and the everyday, stretching through modern history. These films provided a perfect window to view the past - both as "the past" and "the present," telling us how people saw these moments as they unfolded, while reflecting back on their own pasts before that. This form of movement, back and forth, with clear delineations yet infinite variations, feels right for a series centered around such physical activity. I'm reminded of Kon Ichikawa's perpetually looping slow motion depictions of each athlete in a 100m race in Munich '72 - a sequence in Visions of Eight, one of the very best Olympic movies. At least in this regard, time can be rewound, repeated, stretched out, unstoppable if also eternal. The torch is lit and the torch is extinguished, but what unfolds between those flashpoints can fuel a lifetime.

No comments:

Post a Comment