For the last entry in my my Sight & Sound podcast miniseries, chance - and the directors who placed this film much higher than the critics - delivered me the perfect conclusion. Stalker (1979) has been something I've wanted to discuss for years but never found the opportunity...until now. Andrei Tarkovsky's mesmerizing, maddening high art sci-fi philosophical meditation provides plenty of material to consider, but I was most fascinated by those very tensions within its approach. Conveying emotional experiences via visionary sound/image montages at times, and tearing into blunt, direct intellectual debates at others (and sometimes fusing the two), Stalker is enriched by its awareness of what the form is capable of and what it should dance around. Among the subjects I explore: Tarkovsky's frustrations with his environment, the shifting relationships of the three main characters, the concept of the Zone in popular culture, and the significance of the daughter who bookends the movie. This concludes a series which also included Jeanne Dielman, Beau Travail, Close-Up, and Sunrise and I'm also wrapping up this podcast feed and my public film writing/podcasting between with this episode and an essay going up at the same time - although Patreon and Twin Peaks work (and possibly some non-Peaks videos) will continue. I hope you enjoyed the show!

Showing posts with label russian cinema. Show all posts

Showing posts with label russian cinema. Show all posts

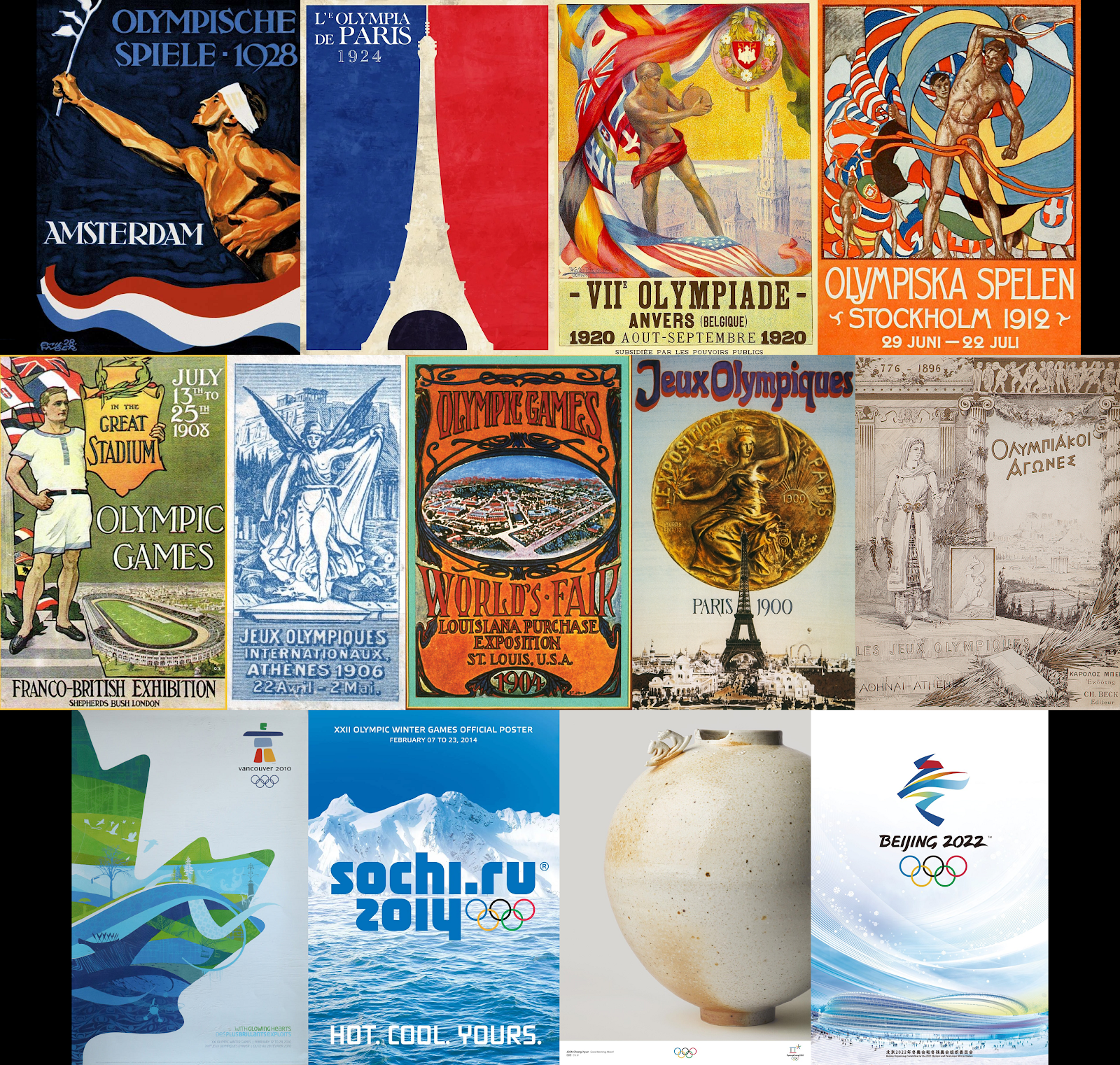

The Olympic Films, part 7 of 7: Summer 1928 / 1924 / 1912 (+ 1920 & 1896 - 1908 bonus) & Winter 2010 / 2014 / 2018 / 2022 (broadcast)

for the introduction & line-up of monthly capsules

running from August 2021 to February 2022

The Olympic Films, part 3 of 7: Summer 1992 / 1988 / 1984 / 1980 & Winter 1960 / 1964 / 1968

for the introduction & line-up of monthly capsules

running from August 2021 to February 2022

Patreon update #48: Training Day (+ Fire Walk With Me as Lynch project, the Soviet War and Peace - 1812 & Pierre, Jonathan, CNN's The 2000s, Twin Peaks fan theories, Ocasio-Cortez clapbacks, Bernie 2020? & more) and preview of Lady Bird review

Just in time for November, my monthly Ethan Hawke series continues with Training Day - a film mostly celebrated for Denzel Washington's iconic performance as a corrupt LAPD cop but also including an Oscar-nominated turn by Hawke as the rookie protagonist. My "Twin Peaks Reflections" attention to the recent Fire Walk With Me essay resumes; I analyze the Twin Peaks movie as a David Lynch project. I also conclude the reading of my War and Peace essay for "Opening the Archive." There are two long sections this week, as I delve into political subjects I discussed on Twitter in "Other Topics" and share extensive listener feedback for my last couple episodes. At the outset of the episode I lay out more specific plans for 2019, as some tiers will shift and a new Twin Peaks project will launch; meanwhile, for my biweekly preview I share parts of an upcoming review of Greta Gerwig's Lady Bird.

Line-up for Episode 47

INTRO

ANNOUNCEMENT - 2019 Plans for 1st/2nd tier restructure & Twin Peaks rewatch

WEEKLY UPDATE/Patreon: 2nd tier biweekly preview - Lady Bird

WEEKLY UPDATE/work in progress: Cinepoem, Mad Men viewing diary, Mary Shelley review

TWIN PEAKS REFLECTIONS: Fire Walk With Me as Lynch project

FILM IN FOCUS: Training Day

OTHER TOPICS: Jonathan, Ollie Klublershturf vs. the Nazis, random TV viewings, CNN's 2000s documentary - I Want My MP3/The iDecade/The Financial Crisis, CGI Lion King, CBS sports montage, John Carpenter's special effects, Dr. Amp's early musical, The Magnificent Ambersons on Criterion, Evangelion on Netflix, Nicolas Roeg & Bernardo Bertolucci died, ridiculous Dear Prudence letter, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez clapbacks, Stephen Hawking vs. Joe Lieberman at 2000 Democratic convention, "Thomas Jefferson" disses Ocasio-Cortez, donut Twitter celebrates the new Democratic Caucus chair, Bernie Sanders' "not racist" statement, should Sanders run in 2020?, Eric Erickson celebrates Augusto Pinochet, podcast recommendations

LISTENER FEEDBACK: my disclaimer about how I'll respond, Michael & Us covers Donnie Darko, Judy as repetition, different versions of the Palmer house, One Eyed Jack's & spirit world, Teresa & the dirt mound, Cooper leading Carrie to her death?, Laura & the ring, Lynch vs. Frost on Judy, do theories overlook flaws?

OPENING THE ARCHIVE: War and Peace (Soviet adaptation)

OUTRO

ANNOUNCEMENT - 2019 Plans for 1st/2nd tier restructure & Twin Peaks rewatch

WEEKLY UPDATE/Patreon: 2nd tier biweekly preview - Lady Bird

WEEKLY UPDATE/work in progress: Cinepoem, Mad Men viewing diary, Mary Shelley review

TWIN PEAKS REFLECTIONS: Fire Walk With Me as Lynch project

FILM IN FOCUS: Training Day

OTHER TOPICS: Jonathan, Ollie Klublershturf vs. the Nazis, random TV viewings, CNN's 2000s documentary - I Want My MP3/The iDecade/The Financial Crisis, CGI Lion King, CBS sports montage, John Carpenter's special effects, Dr. Amp's early musical, The Magnificent Ambersons on Criterion, Evangelion on Netflix, Nicolas Roeg & Bernardo Bertolucci died, ridiculous Dear Prudence letter, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez clapbacks, Stephen Hawking vs. Joe Lieberman at 2000 Democratic convention, "Thomas Jefferson" disses Ocasio-Cortez, donut Twitter celebrates the new Democratic Caucus chair, Bernie Sanders' "not racist" statement, should Sanders run in 2020?, Eric Erickson celebrates Augusto Pinochet, podcast recommendations

LISTENER FEEDBACK: my disclaimer about how I'll respond, Michael & Us covers Donnie Darko, Judy as repetition, different versions of the Palmer house, One Eyed Jack's & spirit world, Teresa & the dirt mound, Cooper leading Carrie to her death?, Laura & the ring, Lynch vs. Frost on Judy, do theories overlook flaws?

OPENING THE ARCHIVE: War and Peace (Soviet adaptation)

OUTRO

Patreon update #47: Steamboat Willie's 90th anniversary & 9 other classic Mickey Mouse cartoons (+ Lindsay Hallam's Fire Walk With Me book, the Soviet War and Peace - Andrei & Natalya, Democrats in the midterms, Vic Berger's Walkaway video, Nazis vs. MAGA normies, Armistice Day, Halloween/political podcast recommendations & more)

Mickey Mouse, Laura Palmer, and Leo Tolstoy star in this week's eclectic podcast episode (with guest appearances by Vic Berger, Kurt Vonnegut, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez). In some ways, though, the lead subject is Lindsay Hallam, an author whom I interviewed last week about her new book on Fire Walk With Me. "Twin Peaks Reflections," continuing its synchronization with my "5 Weeks of Fire Walk With Me" series, discusses that book and the talk we had about. My film in focus becomes films in focus as I celebrate not just the ninetieth anniversary of Steamboat Willie, the first-distributed and first-sound-designed Mickey Mouse cartoon, on November 18, 2018, but also nine more Mickey shorts from the thirties, ranging from sharp black-and-white to lavish Technicolor. These were a lot of fun to revisit.

The bulk of the episode, however, is consumed by a mammoth "other topics" discussion, my first in about a month. There are a few readings or viewings to touch on but, aside from a lengthy segue on Halloween podcasts, the topics are mostly political. A couple weeks after the fact, I finally offer my response to the "blue wave" (or was it?) midterm elections and some of the spillover into the already-coalescing new Congress. I share a hilarious Vic Berger video about a rally gone wrong (including some audio), muse on the ridiculous but unsettling exchanges between fascists and run-of-the-mill Republicans on Twitter, and reflect on the centenary of Armistice Day. And of course, I offer another big round-up of podcast episodes, all featuring a political context but with subjects ranging from existentialism to the Haitian Revolution.

The podcast closes with part one of my War and Peace review from ten years ago, discussing the Soviet adaptation's structure and the parts focused on the characters of Andrei and Natalya. I'll pick up with the 1812 and Pierre sections next week - see you on the other side of Thanksgiving.

Oh and one more thing - early on the episode, I discuss some potential ideas for my approach to both Patreon and Journey Through Twin Peaks in the new year. Expect more concrete plans for this in the next few weeks including some public Patreon posts.

INTRO

THOUGHTS ON MY APPROACH TO PATREON & TWIN PEAKS VIDEOS IN 2019 (plus a brief update on my Lindsay Hallam interview)

TWIN PEAKS REFLECTIONS: Lindsay Hallam's Fire Walk With Me book & my interview with her

FILM IN FOCUS: Steamboat Willie (+ 9 Mickey Mouse shorts from the 30s)

OTHER TOPICS: The 2018 Midterms & Democrats in the House, Hill Street Blues, Mary Shelley and biopics, Frankenstein LIFE special edition, Halloween podcast recommendations, Vic Berger's Walkaway video, Nazis vs. "normie conservatives", Kurt Vonnegut & a centenarian on Armistice Day, political podcast recommendations

OPENING THE ARCHIVE: War and Peace (Soviet version)

OUTRO

The Favorites - The Mirror (#13)

The Favorites is a series briefly exploring films I love, to find out what makes them - and me - tick. The Mirror (1975/USSR/dir. Andrei Tarkovsky) appeared at #13 on my original list.

What it is • Everything is in luminous black and white, as if the images had been etched in a glowing stone. Awakened by a distant whistle, a child (Filip Yankovsky) slides out of bed and walks toward a large doorway. A split-second before the cut, something white floats through the frame, a garment caught in a gusty breeze even though we're inside. Then we are watching a stern man (Oleg Yankovsky) step out of view, revealing the woman (Margarita Terekhova) whose head he has just soaked. Her hair hangs down in an uncanny fashion that suggests her hair is her face (an effect recalled in the Japanese horror film The Ring and its American remake). We float back as she dangles her wet locks back and forth in slow motion; parts of the ceiling collapse in wet chunks, splashing onto the watery surface of the floor while a flame shoots up out of a stove in the background, an act of lonely defiance amidst the indoor torrent. The woman passes across our sight, parting her hair to reveal a strikingly beautiful face which locks eyes with us for a moment - although in fact this is her reflection, caught in several mirrors clustered around each other. We continue to slide away until all is dark. • The scene is set in color, defined by the greenery of the surrounding grass and trees, the brown wood of the log cabin, and the golden-orangish glow cast through the cabin's window. These colors are faded yet somehow still vibrant, exuding a warmth which is soothing, but not quite comforting. The boy and the woman, his mother Maria, huddle outside this cabin and introduce themselves as strangers from Moscow who have been relocated to the countryside. Shivering in the drippy weather, Maria's polite conversation implicitly asks for an invitation inside, but the woman of the cabin (Larisa Tarkovskaya), exuding a quiet defiance, is not particularly forthcoming. The child watches, lips locked and eyes scowling, soaking up the tension without necessarily being able to articulate why it exists. Turning near the window, outlined in the low light's glow, her hair tied in a kerchief so tight it resembles a skull cap, the hostess looks for all the world like a figure out of Vermeer. If the previously described sequence clearly spoke in the silent, subconscious language of dreams this moment plays out as an authentic fragment of reality, poetically pregnant but not revealing its secrets. The significance is locked away beneath the functionality of the gestures and speech. • Between these two marks, a boy (the same actor but a different character) wanders through an empty house. An offscreen chorus builds to an ominous crescendo as a frosty smudge on glass evaporates, and then all is quiet again except for a ringing phone. The boy answers it and speaks to his father (the grown version of the boy we saw in the other sequence), who tells him that when he was his age, during the war, he was in love with a redhead. And then we are back in time, looking at this bundled-up girl as she tramps through the snow. The following series of events, photographed in the pale white, blue, and brown of a Russian winter, could almost stand as a self-contained short film - an instructor (Ignat Danitsev) tries to impress firm but not too harsh discipline on a group of very young adolescents, including the stubborn orphan Asafiev (whose actor I can't find). Asafiev resists his orders and nearly destroys them all with a grenade that fortunately turns out to be a dummy (thinking it's live, the instructor leaps on top of it, ready to sacrifice himself for the hapless child warriors). Then we are suddenly viewing old, scratchy newsreel images of soldiers dragging supplies through icy tundra, thick mud, and rippling waterways. Loud splashes and sighs fill the soundtrack, clearly added afterwards to the pre-existing footage, a present erupting from the past. • I chose all three of these sequences at random, by jumping back and forth across a YouTube video of The Mirror in its entirety. Like fragments half-remembered from a dream, they can hint at hidden treasures. I can't hope to approximate "what it is" in a mere paragraph, however long, so it seemed right to dip inside the film and explore certain moments up close before pulling back to explain why they add up to something so memorable.

Why I like it •

The Favorites - The Man With a Movie Camera (#35)

The Favorites is a series briefly exploring films I love, to find out what makes them - and me - tick. The Man With the Movie Camera (1929/USSR/dir. Dizga Vertov) appeared at #35 on my original list.

What it is • Experimental filmmakers of the twenties had a penchant for "city-poems," documentaries that recorded the daily life of a city, either in short form or, in the case of Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, over the course of an entire feature. The Man With a Movie Camera follows this course with explosive results although - appropriately enough - it "cheats" a bit, using four cities (Kharkiv, Kiev, Moscow, and Odessa) despite implying that we are gazing at a single metropolis. This is in keeping with the spirit of Movie Camera, a defiantly anti-fiction film which is nonetheless lively with creativity. There are a few staged shots, but for the most part this creativity is expressed through manipulation of the image, an anti-"verite" vision of documentary cinema. This ferociously fast visual cascade was radical during the slower-paced silent era and remains startling today. Superimpositions, backwards-motion, kaleidoscopic montages, and buoyant dollies give the movie a sense of endless motion. "Without the Use of Intertitles...Without the Help of a Scenario...Without the Help of Theatre!" the first (and last) title card declares. Vertov, in his early thirties at the time, had already spent years experimenting with revolutionary newsreels and avant-garde shorts, overlapping the two categories and pushing the medium to (and past) its limits. This film was the culmination. If it seemed Vertov was kicking open a door, that door quickly closed: within a decade, severe Socialist Realism was the mandatory state style. Future generations, far afield, would have to pick up where the fiery young turk had left off and today The Man with a Movie Camera seems more relevant than ever. When it unexpectedly cracked the prestigious Sight & Sound top ten for the first time in 2012, David Thomson noted: "Dziga Vertov’s 1929 film is the single work in the new top ten that seems to understand that nervy mixture of interruption and unexpected association" of the online era.

Why I like it •

The Favorites - Ivan the Terrible, Pt. II (#73)

What it is • The Ivan the Terrible films are among the most unconventional biopics of all time: more about gesture and expression than action. Eisenstein stylizes his live actors and physical sets into grotesque cartoons (J. Hoberman notes that the film "approach[es] animation...Nikolai Cherkasov’s stooped, skinny Ivan might equally have been modeled on a Disney vulture"). Even so, Ivan the Terrible Pt. I (1944) comes much closer than Pt. II to conventional biopic format. Its story documents a series of notable events in Ivan's life, from his coronation and victory in battle to the loss of his wife and triumphant return to Moscow after a temporary abdication. The first film also depicts a notable physical transformation, with Ivan slowly morphing from dashing, fresh-cheeked young man to bearded, wizened old(-looking) man. The second film, on the other hand, zeroes in on one specific story, narrowing its scope in both time and space (other than the dazzling checkerboard-court sequence in Poland that opens the movie). The aristocratic boyars who plotted against Ivan throughout Pt. I are now closing in on him in Moscow and only through his diabolical cleverness and dedication is he able to outwit their attempts to humiliate and eventually assassinate him. Although Ivan's wit and charm, contrasted with the devious sobriety of his opponents, secures him as a sympathetic protagonist, he also seems quite grotesque - calling him a "good guy" would certainly be stretching it. This was ostensibly why Joseph Stalin, who had endorsed the first movie, suppressed the second, chiding Eisenstein and Cherkasov for obscuring the motivations for Ivan's "terrible" actions (something Stalin knew a bit about, and must have taken personally). However, Stalin and the censors in his employ also seemed perturbed by the film's avant-garde nature, which takes the experimentation of the first film to new levels. Pt. II mixes garish, hellish colors with stark black-and-white, playing with light and shadow across Ivan's face so that he looks more like an axe murderer than a noble head of state, and distorting its human forms until they exist more as tactile shapes in their own right than easily-understood signifiers. In short, Ivan the Terrible Pt. II is as concerned with form as content, conceiving form as content in a way that simply didn't compute with Soviet preferences for social realism.

Why I like it •

The Battleship Potemkin

This is an entry in "The Big Ones," a series covering 32 classic films for the first time on The Dancing Image. There are spoilers.

The Battleship Potemkin could be subtitled "A Story of the Sea." For while the men who scurry about its frame - those anonymous and amorphous masses - instigate the action, it is the ambiguously gleaming waters around the ship, and the ship itself, that most reflect the narrative arc. When the film begins, the sea is forbidding, isolating, intimidating: a mass of impenetrable emptiness encircling the starving and discontented battleship. Its shimmering presence heightens our impression of the sailors as imprisoned by their circumstances, and zeroes our focus in on the ship that holds them; after all, there's nothing else to look at, for them or for us.

Yet the film concludes with another shot of these waters and suddenly our interpretation is quite different. At this point the battleship Potemkin steams toward the squadron sent to shoot it down, only to discover that the other ships have been overtaken by sympathetic sailors, more interested in saluting than shooting the mutinous barge. And suddenly the sea is an open field, a liberating space upon which anything is possible. Its shimmers seem friendly winks, its little waves infinite possibilities, its wide-open landscape a heroic horizon. Eisenstein's title tells us that the ship is waving the flag of freedom and it's as if this banner is clearing the air, swatting away the mosquitoes of reaction and the haze of oppression, parting the waves as crisply and cleanly as the ship's bow itself.

Bed and Sofa

Husband and wife are lying in bed, early in the Moscow morning. Kolia (Nikolai Batalov), the husband, is up first, groggy but awakened by the couple's energetic pet cat, who's leapt onto the bed. Mischievously, he grabs ahold of the kitty and shoves it in his sleeping wife's face. Liuda (Lyudmila Semyonova) reacts as any interrupted sleeper would, batting it away and jerking up from her comfortable recline. Rubbing her eyes, smoothing down her bobbed hair and bangs, she glances at the grinning man-boy in bed next to her with a mixture of amusement and irritation. He laughs, but he's playing with fire by provoking her so. Before the day's over, he'll have introduced a creature much more threatening into the marital bed, even if old Red Army buddy Volodia (Vladimir Fogel), visiting from out of town, is initially relegated to the sofa.

Husband and wife are lying in bed, early in the Moscow morning. Kolia (Nikolai Batalov), the husband, is up first, groggy but awakened by the couple's energetic pet cat, who's leapt onto the bed. Mischievously, he grabs ahold of the kitty and shoves it in his sleeping wife's face. Liuda (Lyudmila Semyonova) reacts as any interrupted sleeper would, batting it away and jerking up from her comfortable recline. Rubbing her eyes, smoothing down her bobbed hair and bangs, she glances at the grinning man-boy in bed next to her with a mixture of amusement and irritation. He laughs, but he's playing with fire by provoking her so. Before the day's over, he'll have introduced a creature much more threatening into the marital bed, even if old Red Army buddy Volodia (Vladimir Fogel), visiting from out of town, is initially relegated to the sofa.October

Years ago, I saw a few brief scenes from October which engendered in me a passionate desire to see the whole movie. One moment stood out especially - Eisenstein cuts between a group of cartoonish bourgeois women beating a man with umbrellas and a drawbridge going up, with a cart and dead horse hanging from the precipice. Eventually the cart tumbles down the broad, erect face of the bridge, which is beginning to resemble a skyscraper. The horse finally plummets as well, over the other side of the bridge, into the water. The cutting, the movement onscreen, the vividness of the photography: all added up to one of the most rhythmic, hypnotic, and startling uses of cinema I'd ever experienced. Another sequence which stayed with me was the juxtaposition of Kerensky with the mechanical peacock - again, the cutting between the two figures, the movement within the frame, created a marvelous sense of tension and release, almost musical.

Years ago, I saw a few brief scenes from October which engendered in me a passionate desire to see the whole movie. One moment stood out especially - Eisenstein cuts between a group of cartoonish bourgeois women beating a man with umbrellas and a drawbridge going up, with a cart and dead horse hanging from the precipice. Eventually the cart tumbles down the broad, erect face of the bridge, which is beginning to resemble a skyscraper. The horse finally plummets as well, over the other side of the bridge, into the water. The cutting, the movement onscreen, the vividness of the photography: all added up to one of the most rhythmic, hypnotic, and startling uses of cinema I'd ever experienced. Another sequence which stayed with me was the juxtaposition of Kerensky with the mechanical peacock - again, the cutting between the two figures, the movement within the frame, created a marvelous sense of tension and release, almost musical.I sought out October for a while, trying to order it through a video store without luck (though the clerk informed me that Coppola had decided to become a director after seeing October for the first time). Finally I saw it on a big screen ... and was disappointed. What was brilliant in short snippets didn't quite hold together in long form. There was not enough of an arc to tie in all the effective moments, and the didactic, propagandistic aspect which was easy to overlook for a few minutes became overbearing over the course of two hours. The lack of central characters also had an unfortunate effect - while relatively anonymous ensembles are a regular feature of Eisenstein's silent work, they're usually smaller in number and more distinctive in appearance and behavior; here, the drama is dispersed too widely, and becomes diffuse.

Upon re-viewing the film for the first time in years tonight, my opinion largely remains the same. However, and this is a big however, the final half-hour is excellent and ranks with Eisenstein's very best work. It's a strong finish, not quite enough to make me see the whole film as a masterpiece, but powerful nonetheless. Here Eisenstein ties his bombastic, electric montage agitprop to a more focused narrative (after spanning months and several locations, he settles on the night of October 25 for the last 30 minutes) and a more humanistic aesthetic - several faces begin to emerge from the crowd, lending the "symbolic" proletariat a soul. There's also a fascinating ambivalence in Eisenstein's use of art, particularly sculpture, which manages to represent both the overbearing power and privilege of the upper classes and the romantic spirit of the revolutionaries. All in all, it's a rousing finale and remains one of the more effective depictions of revolution onscreen.

This post was originally published on The Sun's Not Yellow.

Ivan the Terrible

Over the course of two films, released fourteen years apart due to Soviet censorship, legendary director Sergei Eisenstein chronicles the infamous Russian tsar's ascension to and assertion of power. Ivan (Nikolai Cherkasov) begins as a handsome young prince, crowned at the opening of Part I while the corrupt nobles whisper conspiracies under his very nose. By the end of Part II, Ivan is a wizened, shrewd tyrant, foiling an assassination plot by using a simple-minded relative as bait. In between, he leads troops into battle, throws decadent parties, loses a wife to poison, and is betrayed repeatedly until his paranoia makes him wise beyond his years - and authoritarian beyond his foes' wildest expectations.

Over the course of two films, released fourteen years apart due to Soviet censorship, legendary director Sergei Eisenstein chronicles the infamous Russian tsar's ascension to and assertion of power. Ivan (Nikolai Cherkasov) begins as a handsome young prince, crowned at the opening of Part I while the corrupt nobles whisper conspiracies under his very nose. By the end of Part II, Ivan is a wizened, shrewd tyrant, foiling an assassination plot by using a simple-minded relative as bait. In between, he leads troops into battle, throws decadent parties, loses a wife to poison, and is betrayed repeatedly until his paranoia makes him wise beyond his years - and authoritarian beyond his foes' wildest expectations.The film is a masterpiece - the above plot description guides the action, but the essence of the movie is in the extreme close-ups Eisenstein lavishes upon the bizarre faces of his players, the lavish yet cleverly designed set pieces (dinners with huge white, and later black, swan statues; a diplomatic detente in which the figures are placed on the checkered floor like chess-pieces), and the magnificent score contributed by Prokofiev. One should not expect a historically accurate recreation, a politically correct manifesto, nor even an especially straightforward narrative; to enjoy the movie one has to appreciate the campy effects Eisenstein employs and recognize that their campiness is not really unintentional. Even Ivan the Terrible seems in on the joke, half-flirting with an effeminate usurper just to get his way, wickedly grinning as he poses for Eisenstein's flamboyant camera. Part II is even better than Part I, if only because it further abandons the dutiful rollout of Ivan's rise to power for the immersion in his decadent, paranoid, baroque milieu.

Eisenstein had been one of the signature pioneers of Soviet silent film, when his films focused on the power of "montage" - rapidly cut sequences which often employed visual metaphors and rhyming images. Ivan the Terrible employs a wider variety of tricks, but the execution is still tight, controlled, and rhythmic - not in a cold fashion, but bursting with enthusiastic passion. As Stalin clamped his iron fist down on the Marxist state and narrowed the range of the arts, preferring drab socialist realism to inventive avant-garde agitprop, it was hard to see where Eisenstein fit in this totalitarian vision. He was freed up to create Alexander Nevsky, a heroic history film and his first collaboration with Prokofiev, in the late 30s. But the film's anti-German slant became a mark against it with Stalin's ever-shifting political line and it was a good five years before Eisenstein was cautiously given permission to proceed with Ivan, seen as a tribute to the latter-day despot. How times change! Suddenly ostentatious monarchism, nationalistic xenophobia, and subservience of the masses to the rule of one man were celebrated in the name of the Leninist revolution. Apparently, Stalin approved of Part I, was dismayed by Part II (whose release was delayed until after his death), and canceled Part III. Eisenstein's career was over, he died at fifty, and the Soviet cinema entered its deepest deep freeze, only to be alleviated with Joseph the Terrible's own demise. Today, some see Ivan the Terrible as a Stalinist apologia, while others find in it a subversive attack on the dictator. Perhaps both viewpoints are correct, which only adds to the attraction of this warped classic.

This review was originally published at the Boston Examiner.

Strike

The title of this post does not refer to my (unintentional) absence from this blog - though 5 days is by far the longest sabbatical I've taken since starting up in July. It's not that I don't have anything to write about it - indeed, I've pretty much got the rest of December mapped out: a "paranoia" series featuring The Parallax View, The Conversation, and the 90s Will Smith movie Enemy of the State (which is bizarrely a semi-spin off of The Conversation); the conclusions to the Auteurs and "Twin Peaks" series; a few write-ups on recent DVDs I've purchased or received as gifts (my 25th birthday passed not so long ago) - Some Came Running, Kiss Me Deadly, and the long-promised Disney World War II cartoons; and perhaps a series of shorter-than-usual reviews on films I've seen in the past few weeks but didn't take the time to write up: the weirdly enjoyable buddy flick Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the amazing Bing Crosby alcoholic performance in The Country Girl, and maybe even the intriguing but as-yet-unseen Notes from Underground, a modern update of one of my favorite novels, starring Sheryl Lee whom I've yet to see in anything other than a David Lynch project (she of course is the reason I discovered and Netflix'd the movie, way back in August). So anyway, as you can see, there's plenty on the back burner which will be tackled before I take an even longer break for Christmas and New Years, returning in 2009 for all kinds of fun & games which I'll avoid previewing now. Why the avoidance of blogging if I have all this raw material? Blame it on the aftereffects of whatever that chemical is in the Thanksgiving turkey - I was too tired to engage. Or something. At any rate, if my absence was a "strike," it's now coming to an end with - appropriately enough - Strike, the 1925 Sergei Eisenstein debut.

The title of this post does not refer to my (unintentional) absence from this blog - though 5 days is by far the longest sabbatical I've taken since starting up in July. It's not that I don't have anything to write about it - indeed, I've pretty much got the rest of December mapped out: a "paranoia" series featuring The Parallax View, The Conversation, and the 90s Will Smith movie Enemy of the State (which is bizarrely a semi-spin off of The Conversation); the conclusions to the Auteurs and "Twin Peaks" series; a few write-ups on recent DVDs I've purchased or received as gifts (my 25th birthday passed not so long ago) - Some Came Running, Kiss Me Deadly, and the long-promised Disney World War II cartoons; and perhaps a series of shorter-than-usual reviews on films I've seen in the past few weeks but didn't take the time to write up: the weirdly enjoyable buddy flick Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the amazing Bing Crosby alcoholic performance in The Country Girl, and maybe even the intriguing but as-yet-unseen Notes from Underground, a modern update of one of my favorite novels, starring Sheryl Lee whom I've yet to see in anything other than a David Lynch project (she of course is the reason I discovered and Netflix'd the movie, way back in August). So anyway, as you can see, there's plenty on the back burner which will be tackled before I take an even longer break for Christmas and New Years, returning in 2009 for all kinds of fun & games which I'll avoid previewing now. Why the avoidance of blogging if I have all this raw material? Blame it on the aftereffects of whatever that chemical is in the Thanksgiving turkey - I was too tired to engage. Or something. At any rate, if my absence was a "strike," it's now coming to an end with - appropriately enough - Strike, the 1925 Sergei Eisenstein debut.War and Peace

Opening on barren, empty battlefields, whizzing past telephoto close-ups of grass and dirt with a bizarre, avant-garde audio collage enveloping the soundtrack, then soaring into the sky through clouds to reveal a breathtaking panorama, War and Peace immediately confounds expectations that it will be pedantic, stuffy, and overly solemn. Which is appropriate because the book it is adapting is similarly light on pretension and nimble in style, a fact often overlooked when regarding the tome's massive length, all-inclusive title, and daunting literary reputation. Like Tolstoy, Soviet director Sergei Bondarchuk delves into his material with gusto. War and Peace stutters and missteps more than the book it adapts - though it is often smoother as well - but Tolstoy's masterpiece also has an uneven quality - which is ironically one of its major strengths.

Opening on barren, empty battlefields, whizzing past telephoto close-ups of grass and dirt with a bizarre, avant-garde audio collage enveloping the soundtrack, then soaring into the sky through clouds to reveal a breathtaking panorama, War and Peace immediately confounds expectations that it will be pedantic, stuffy, and overly solemn. Which is appropriate because the book it is adapting is similarly light on pretension and nimble in style, a fact often overlooked when regarding the tome's massive length, all-inclusive title, and daunting literary reputation. Like Tolstoy, Soviet director Sergei Bondarchuk delves into his material with gusto. War and Peace stutters and missteps more than the book it adapts - though it is often smoother as well - but Tolstoy's masterpiece also has an uneven quality - which is ironically one of its major strengths.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)